by Claire Allen-Johnstone and Helen Butler-Watts

A little while ago the V&A was given an exciting group of over 3,500 textiles that were once part of the Design Library of Courtaulds Textiles plc.

We need to look back over the last 300 years or so to understand this company and its Design Library; it was between 1685 and 1700 that the Protestant Courtaulds family escaped religious persecution by leaving France for England. They originally worked as merchants and gold and silver smiths but founded a textiles business in 1816. Like many Huguenots (French Protestants of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) and their descendants, they worked with silk, producing silk yarn and fabric. The family business thrived throughout most of the nineteenth century, making much of its money from black mourning crêpe, popularised in the United Kingdom and elsewhere by Queen Victoria’s (Alexandrina Victoria, queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, 1837-1901, empress of India, 1876-1901) extended mourning for her husband Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz Karl August Albrecht Immanuel, Prinz von Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, prince consort, consort of Queen Victoria, 1857-1861), who died in 1861. When formal mourning ceased to be so widely practiced in the United Kingdom towards the end of the century the company suffered, but its decision to buy the exclusive British rights to the production of artificial silk in 1904 proved auspicious despite some initial teething problems. In 1932 Samuel Courtauld founded the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, England, now a prominent university college with an impressive art gallery, and in the 1960s and 1970s Courtaulds acquired and developed a range of textile and clothing companies. The business also diversified in this period, making industrial products including plastics and specialist chemicals. In the 1980s Courtaulds experienced both problems, connected to recession and increased international competition, and successes, before forming two separate businesses in 1990: Courtaulds plc and Courtaulds Textiles plc. These companies were acquired by AkzoNobel, a Dutch company, and American corporation Sara Lee Corporation in 1998 and 2000 respectively.

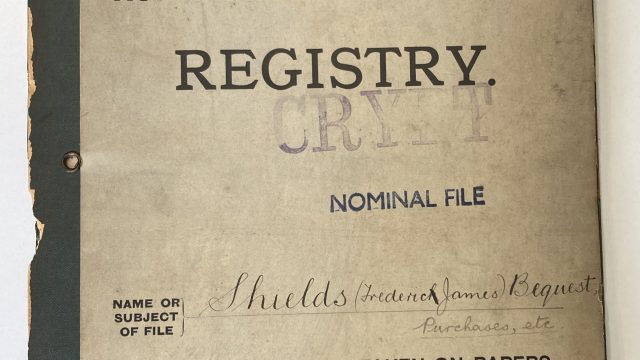

Sara Lee Corporation had taken on not only a company but also its Design Library. The Courtaulds Design Library principally contained records from Courtaulds factories and a large collection of fabrics that the company took possession of in 1963 when they acquired Morton Sundour Fabrics Ltd., a British firm well-known for their use of ‘unfadable’ dyes and their experimental offshoot, Edinburgh Weavers. Many of the textiles in the Courtaulds Design Library were once in Morton Sundour’s own reference collection. The Courtaulds Design Library provided inspiration for Courtaulds designers and was available to customers. The Design Library was generously donated to the V&A, and the hope is that these materials will continue to provide inspiration and food for thought.

In order to make these records and fabrics as publicly accessible as possible the V&A needed to catalogue them. The V&A Archive of Art and Design team started to catalogue the paper-based records and historical sample books in the early 2000s, and this project is almost complete (the team still needs to catalogue some fragments of fabric recently transferred from the Furniture, Textiles & Fashion Department and to update Search the Archives). Between 2018 and 2019 a large group of Staff and Volunteers at the Clothworkers’ Centre in Blythe House, London photographed, labelled, and recorded information about the Design Library’s collection of over 3,500 textiles, most of which are twentieth-century furnishing fabrics.

This post focuses on the project at the Clothworkers’ Centre. Those of us who worked on the project have been stunned by the variety of the fabrics in this collection. Below we discuss 10 pieces as a means of introducing the collection and what it has to offer. Do check out the rest of the objects on Search the Collections (T.250-2018 to T.3807-2018), and feel free to email clothworkers@vam.ac.uk if you would be interested in seeing some for yourself at the Clothworkers’ Centre. For more information about the Centre please see the Clothworkers’ Centre page on the V&A website. There you will also find out about the planned closure of the Centre between 18 December 2020 and spring/summer 2023 to facilitate the relocation of numerous V&A collections to the new Collections and Research Centre in Stratford’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London.

The reference for the materials held by the Museum’s Archive is AAD/2002/7. A summary description can be found online and the full records will appear on Search the Archives soon. This part of the archive is also available for consultation, in the Blythe House Archive & Library Study Room.

1.

The Scottish hand loom weaver Alexander Morton founded Alexander Morton & Co., the parent company of Morton Sundour Fabrics, in 1870 in Darvel, Scotland. In the late nineteenth century Morton’s son James oversaw collaborations between leading Arts and Crafts designers but set out to show that mechanised production could rival the beauty of hand-made textiles. The company acquired a power loom in 1875 and set up a large factory in Darvel, where this textile was produced about fifteen years later. The luxurious silk fabric with Italian-style floral tracery is an example of one of Alexander Morton & Co.’s reversible double cloths.

2.

In 1900 Alexander Morton & Co. expanded to a new headquarters at Dentonhill Works in Carlisle, England. Here, James Morton began his quest to produce lightfast dyes. The resulting ‘unfadable’ ‘Sundour’ textiles, launched in 1906, proved so profitable that the company changed its name to Morton Sundour Fabrics in 1914. This 1920s fabric is representative of the bright and lush textiles produced by the company at this time. Such textiles attracted Liberty & Co. in London, amongst other clients. This object also speaks to the great interest in Iranian decorative art of the Safavid period (1501-1722) featuring scenes with figures in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe and America. Here, scenes in the Safavid style are accompanied by motifs not drawn directly from Iranian art including the large palms.

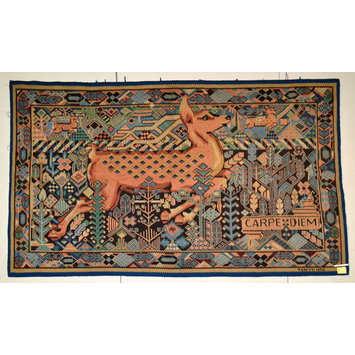

3.

In the spirit of William Morris, who revived traditional hand-made textile arts in nineteenth-century Britain, James Morton established a group of craft workshops in 1920 under the name Scottish Folk Fabrics. The workshops, situated in the Scottish village of Corstorphine, appealed to James Morton’s artistic tastes, more so than his industrial work at Morton Sundour, despite his long-standing commitment to such work. The collection now held by the V&A contains beautiful examples of Scottish Folk Fabrics appliquéd bedspreads, embroidered cushions, needlework and hand-woven tapestries such as this panel, designed by the head of the project Ronald Simpson. Morton’s design preferences and interest in artisanship were also the catalysts for Edinburgh Weavers, which has been described as the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the Morton enterprise (Jackson, 2012, p.9). Through this offshoot, founded in 1928, Morton sought to produce textiles that measured up to his understanding of artistic and technical merit, collaborating with leading twentieth-century artists to create what many see as some of the finest textiles of the period.

4.

This is one of many batik or imitation batik pieces in the Design Library. The batik technique developed in Asia hundreds of years ago, and is particularly strongly associated with Java, an Indonesian island. The process involves using wax to protect areas of cloth from dye. Batik has also been popular in Europe, particularly notably in the 1920s, when centres of production sprang up in countries including the Netherlands, which had a long colonial trading connection with Asia. The technique has been imitated as well as replicated, and Morton Sundour was among those who made faux batiks, such as T.2700-2018. No doubt their designers were inspired by real batiks in the company’s Design Library, such as the textile shown above. Likely made in Java, but with a European interpretation of an Asian design, this piece highlights the cross-cultural nature of many batiks and imitation batiks.

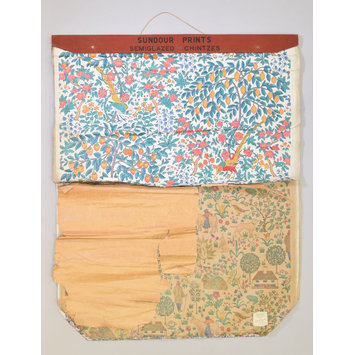

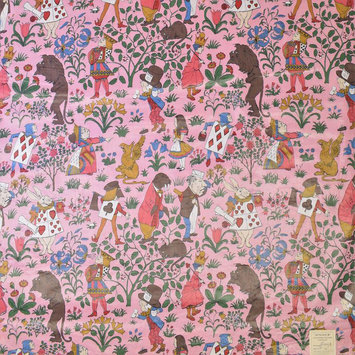

5.

Fruit, flowers, penguins, elephants and peacocks burst from this swatch book, which collects together 26 Morton Sundour patterns. These chintz (glazed printed calico, in this case semi-glazed) fabrics show James Morton’s association with renowned British designers Sidney Mawson and C. F. A. Voysey. Voysey’s well-known Alice in Wonderland pattern appears in the book in multiple colours. We were particularly interested in the dark-haired Alice—something we’ve never seen before.

6.

James Morton’s collection of historic textiles and fabrics from contemporary manufacturers formed an important resource for the designers at Morton Sundour. One of the biggest groups in the collection transferred to the V&A is a set of damasks, brocades and velvets from the Italian manufacturer Pastori & Cassanova, bought at auction around 1940. Our favourite design is this cloud pattern. This fabric is a damask, a figured textile with a reversible pattern formed using one warp yarn and one weft yarn. In this case it was woven on a jacquard loom.

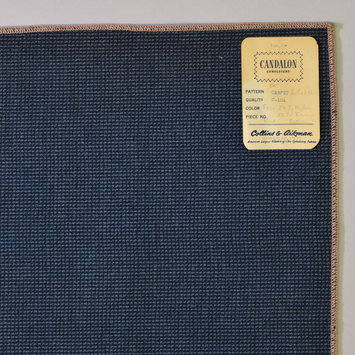

7.

Courtaulds became involved in textile manufacture for car interiors in 1978. Their Design Library contains an example of a carpet made for Cadillac, an automobile brand founded in the United States. The carpet was made by the American firm Collins & Aikman. Courtaulds Automotive Products was sold to Collins & Aikman in 1997.

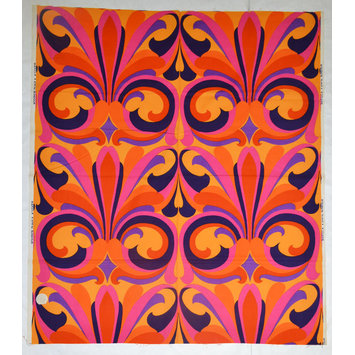

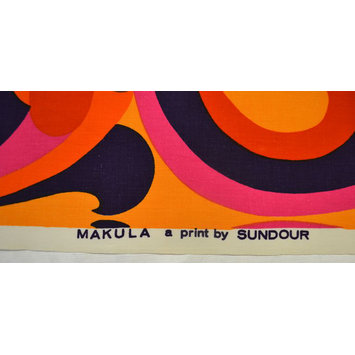

8.

Alexander Morton & Co. became strongly associated with bright colours following the release of their ‘Sundour’ fabrics, a reference to the sun and possibly the fastness of the company’s dyes, as the word dour implies unyieldingness amongst other qualities. This textile is a particularly striking example of the firm’s use of bold colours. The shades and psychedelic pattern suggest that it was designed in the ‘Swinging Sixties’. The name ‘Makula’ remains a mystery as the family of successful Polish aviators with this surname had not risen to prominence by this date.

9.

Flame stitch, the embroidery technique which inspired this fabric, is also known as Irish stitch, Hungarian stitch, Florentine stitch and Bargello stitch. As these names suggest, its precise origins remain unknown. The technique was used on early pieces such as eighteenth-century maniple CIRC.661-1925, probably made in Italy. T.2168-2018 is a modern take on this traditional technique in the sense that it is not embroidered and was probably made by running a machine similar to those used for tufting over a thick woven ground. The effect is very convincing.

10.

A box of miscellaneous items that we worked on at the end of our cataloguing project presented us with, amongst other things, four pieces of underwear with the Marks & Spencer ‘St Michael’ logo. This branding is nostalgic for some, having been used by the British firm Marks & Spencer between 1927 and 2000. Courtaulds was a major supplier to Marks & Spencer, predominately for lingerie ranges. Sticky notes reading ‘Courtaulds lingerie’ attached to floral fabrics throughout the collection now housed at the Clothworkers’ Centre suggest that designers would search through the Courtaulds Design Library sourcing patterns for clothing.

See further

Jackson, Lesley. Twentieth-Century Pattern Design: Textile and Wallpaper Pioneers. London: Mitchell Beazley, 2002.

Jackson, Lesley. Alastair Morton and Edinburgh Weavers: Visionary Textiles and Modern Art. London: V&A Publishing, 2012.

Parry, Linda, et al., British Textiles: 1700 to the Present. London: V&A Publishing, 2010.

This post was edited by one of the authors (Claire Allen-Johnstone) on 29 March 2021 as part of work on sensitive terminology and topics. Some additional changes were made on the same date to further improve the post.

I grew up with the Morton Scottish Folk Fabrics workshop at the bottom of our family’s garden. It’s fascinating to read this detail of the work that was carried out there. Thank you .

This information is intriguing.

I joined Courtaulds Furnishings in 1977 as a graduate Textile Designer, having been sponsored at Bradford University by Courtaulds.

I went on to be a textile designer at Ford Motor Company, where some Courtaulds Automotive textiles were used. I then moved to Austin Rover and here Courtaulds Automotive was a major supplier.

I would be interested to know if it is possible to visit the collections you describe. A lot of this would have been held in Carlisle originally, I remember many files and books in the top floor design studio there.

What do you think?

Martin Peach