“Costume of Manila(?)” is a note that caught my eye, penned in a register in the V&A’s Art, Architecture, Photography and Design (AAPD) department. Describing eight watercolours by the same hand, the hesitant reference to the Philippine capital – and attribution to “a native artist(?)” – sparked my curiosity, which grew to enthusiasm upon viewing the images and recognising Tagalog words in their captions.

“This piece cannot be finished,

I don’t know why the owner is in haste,

he wants to wear it for Epiphany,

but how can I make it quickly

when he is still lacking in funds?”

Cover image and above: Details from a watercolour depicting a woman working, artist unknown, about 1840s, Philippines. Museum no. 531. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. With caption translation.

As someone of mixed British-Filipina ancestry, I’ve loved being able to catalogue some of the V&A’s objects from Southeast Asia. Even so, finding something directly connected to the Philippines has been rare! Through Documentation for Access (a V&A project improving database records for historic acquisitions), overlooked works like these are now discoverable, both digitally on Explore the Collections and in-person via Order an Object or our Study Rooms.

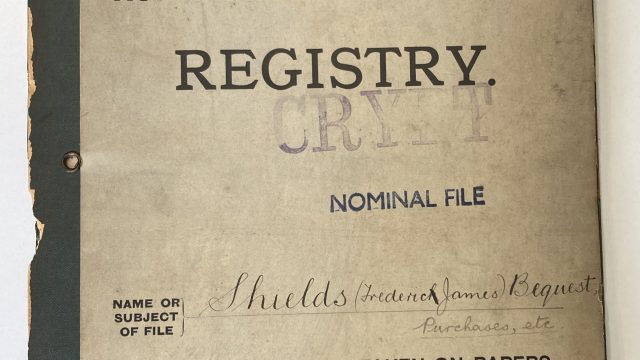

The watercolours have very early accession numbers, showing they were among the first objects to enter the collection. From the register, we know they were formerly at Marlborough House, home to the Museum of Manufactures (a pre-cursor to the V&A) in 1852. This, combined with a dated watermark on their sheets – from British papermakers, J Whatman in 1835 – confirms the window in which they were made. Their resurfacing also brought a second corresponding set of watercolours to light, painted on a red ground in a different technique, with the same inscriptions.

Untypical types

Both sets are fascinating examples of tipos del país (‘types of the country’) – a genre popularised in 19th century Manila during the Spanish colonial period. These small paintings portrayed local people in so-called ‘costume’ or typical dress, and were used by textile merchants, or collected by foreign traders as ‘exotic’ souvenirs. The form is associated with Damián Domingo (1796 – 1834), famed as the ‘father of Philippine painting’ and for establishing the first Philippine art academy. The V&A’s National Art Library holds a volume of vibrant examples attributed to Domingo (although, recent research shows this is likely a finely rendered Chinese copy).

Tipos del país were often inscribed with Spanish titles that ‘othered’ or flattened subjects into socio-ethnic categories. By contrast, the Tagalog captions here are highly unusual. Through lines of rhyming verse, these eight figures have been animated to reveal nuanced, often humorous, layers of personality – from the young man pretending to study, to the working woman bemoaning being rushed. Written mostly in first-person, they seem to playfully subvert the genre and re-centre the Filipino voice.

At the same time, these artworks evidence 19th century Manila as a complicated fusion of East and West. From the British-imported paper, to the Spanish-transliterated spellings, to the mixing of native and European dress, legacies of Empire can be traced in their form and fabric.

Many voices

Collaborative cataloguing – both within and beyond the museum – can redress the Eurocentric lens and gaps in our documentation. Working across departments enables knowledge-sharing; for instance, familiarity with the betel boxes in our Southeast Asia collection helped me confirm one figure as a betel-nut seller (rather than a ‘female with chestnuts’, as misidentified in the historic AAPD register). The old Tagalog verses, deciphered with support from family members, are now included in the records.

Additionally, all sixteen watercolours have been added to the online platform, Mapping Philippine Material Culture. Led by Philippine Studies at SOAS, the project collates an open-access inventory of Filipino objects held in institutions worldwide. This has led to new research by Dr Maria Cristina Juan, exploring the unique meanings and contexts of these tipos del país and highlighting them within wider academic and international networks. The response has opened new conversations and discoveries – from collectively-improved translations to possible links to Justiniano Asunción (1834 – 1901), who trained at Domingo’s Academia de Dibujo y Pintura. One analysis identifies the figure in 531 as a jeweller, giving evidence of women’s diverse professions in Manila in the 1800s.

To me, this process of enhancing records with new information shows that our knowledge is fuller and richer when multi-vocal. It shows the importance of connecting our objects with the communities to whom they are most meaningful – and centring their expertise through collaboration beyond the museum.

Personally, I would love to see better Filipino representation at the V&A – not just in the object stories we tell, but in who gets to tell them. As the UK’s largest Southeast Asian diaspora (and with big communities in Kensington and Newham – home to two of the V&A’s London sites), can we do more to amplify the Filipino voices of not just 19th century Manila, but the diverse London and Britain of today?

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Discover more about these artworks and their Tagalog verses – including a full set of improved translations – via the Mapping Philippine Material Culture project.

One of the best blog posts here in some time – many thanks – both through surprising subject and persuasive argument. I especially like the strong point, ‘our knowledge is fuller and richer when multi-vocal’.