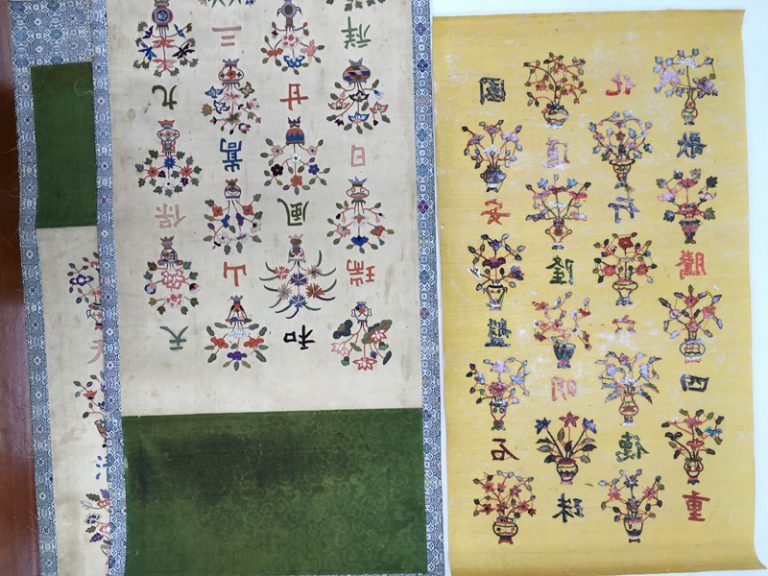

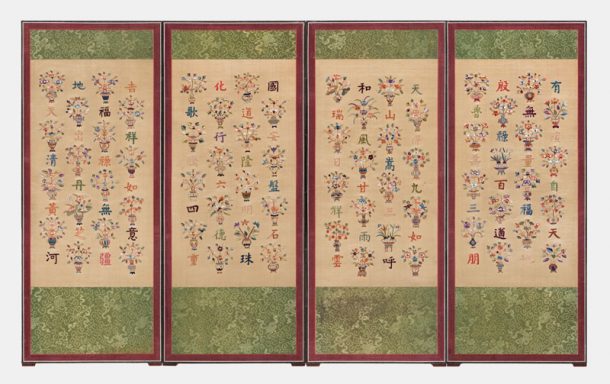

In 1991, the Victoria and Albert Museum acquired four mounted scrolls (FE.29 to 32-1991) as a share of a donation made by Katherine Talati, a British painter of Indian (Parsee) heritage. Believed to date from the twentieth century, they once formed part of a folding screen (Jasu hwachogilsangmun byeongpung), which originally consisted of eight panels. The panels have a textile background, a cream, satin-weave silk, which is embroidered with recognizable flowers displayed in antique vases or pots. These flower arrangements alternate with auspicious Chinese characters. Each panel was mounted top and bottom with a Korean green silk damask and then framed with a floral-patterned silk brocade of Chinese origin. The backing paper was a burnished Chinese xuan zhi adhered to the first lining of Korean paper known as hanji.¹ This backing was probably added later alongside the Chinese brocade when the panels were remounted as scrolls. On further checking it was discovered that the hanji lining of panel two (FE.32-1991) had Chinese calligraphy, written in black ink, that became apparent in transmitted light. The original rich yellow colour of the background silk was also revealed when the old linings were removed during conservation. Interestingly, the organic-dyed twisted silk threads of the embroidery were not badly faded (Figure 1). These elegant floral designs would have been executed to a specific design using a paper template. Templates were drawn and numbered in relation to the screen panel sequence, which made identification of the order of the V&A panels as the first, second, seventh and eighth panels possible.²

During an assessment of these mounted panels with Dr. Rosalie Kim, curator of Korean Art, it was decided they could not be displayed in their current format. Culturally, the panels should be understood as part of a folding screen, albeit only having four of the eight original panels. Professor Park Chisun, a conservator of Korean art based in Seoul, was approached for expert advice on the remounting of these panels and suggested that it become an educational venture. Through various grants and the generosity of Professor Park, the author was invited to the Jeongjae Conservation Studio to join her team to recreate the four-panel screen.

Traditional materials and techniques have recently seen a resurgence in Korean conservation. In the past there had been a blurring of the lines between Chinese, Japanese and Korean materials. The similarities in style are partly due to the close geographical proximity and partly to historical ties. The Korean mounting technique had virtually disappeared for various reasons including colonial legacy and resulting wars. The evolution of paper making and silk weaving within each country gave rise to specific cultural norms. Research and publications have documented these distinctions and made them more accessible, which has led to improved communication and a willingness to understand the nuances of screen mounting. In the past these were not necessarily understood, especially by Western conservators, who through lack of access to specific materials and techniques had to rely on what was readily available – normally Japanese paper and mounting style. In recent years this has changed and part of the experience at the studio was to learn about the use of hanji paper, Korean hand-woven silk, and indigenous natural dyes to inform work on other Korean screens within the V&A collection.

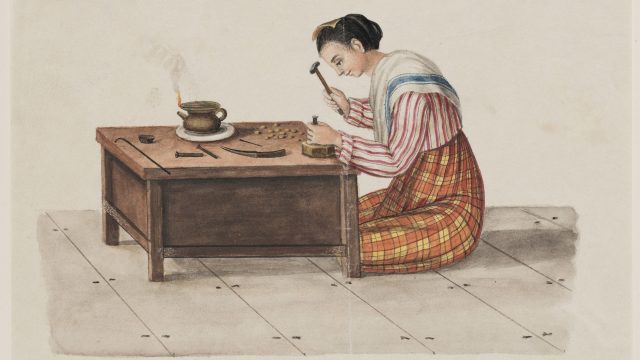

The wooden core of the four-panel screen was constructed by a local carpenter using paulownia wood, a strong, even-grained, pale wood commonly used in Asia. The new latticed wooden panels were then covered with several layers of hanji, each paper layer having a slightly different purpose: alternating single sheets with a pocket layer rather like a duvet creates a stable and cushioned surface for mounting the textile panels. The hinge attachment is complicated and a small prototype was made in order to understand the alignment, measurements and application of the hinges (Figure 2). After adhering with wheat starch paste, these were left to dry with weights to keep the structure perfectly square. Part of the unique mounting style of a Korean screen is the textile front and back cover, which is also used to cover the hinges. The coarse dark blue linen cloth is attached and left to dry (Figure 3). Hand-made bands of silk and paper are used to frame the embroidered panels. Both are dyed using indigenous plant material, in this case, madder, alder cones and purple gromwell. The silk, which is hand woven in narrow strips, is washed and then dyed. This silk is scarce because the weavers are usually older women and are not being replaced by younger weavers. This problem is not unusual as Korean hanji production also has this succession issue.³

The finished screen was displayed in the exhibition Restoring the Legacy of Korean Paintings at the National Palace Museum of Korea in Seoul in September and October 2019. This exhibition highlighted the conservation of overseas Korean collections by Jeongjae studio with the support of the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation (OKCHF). It was accompanied by the first International Symposium on the Conservation and Restoration of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage, during which Professor Park and curators of Korean art from overseas museums, recipients of the OKCHF conservation grant, presented papers. The embroidery panels will be displayed for the first time, in their original form of a folding screen, in the Korean Gallery of the V&A from February 2020 onwards (Figure 4).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Park Chisun and her team for sharing their expertise; to the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation for supporting the conservation of these panels; and to The Plowden Trust for the grant that enabled me to travel to Seoul.

References

1. Lee A., Hanji Unfurled: One Journey into Korean Papermaking, The Legacy Press 2012

2. Kim, Rosalie, ‘Hwachogilsangmun embroidery panels in the Victoria and Albert Museum,’ in the 1st International Symposium of Conservation and Restoration of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage. Restoring the Legacy of Korea Paintings, eds. Cha Miae et. al. (Seoul: Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation, 2019), 128-139.

3. Interview with Jang Seong Woo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7mPGaa_NMA