As part of a long term and ongoing project to digitize the whole of the V&A’s collection, a large archive of Middle East topographical photographs dating from the mid-19th century to early-20th century is being analysed and systematically catalogued.

These views first came into the collection through the National Art Library (NAL) which began acquiring topographical views as a way to extend the resources of the Museum. Beginning in the 19th century, Western photographers travelled widely within and outside Europe, transporting unwieldy equipment and enduring difficult working conditions. The images they produced combined commercial, documentary, social, and artistic value which the Museum made available to students and artists. In 1977, The Photography Collection was formally transferred from the NAL to the newly established Department of Prints and Drawings.

A visiting scholar’s recent request for views specifically of Cairo put in motion an in-depth investigation of the catalogue records of a group of photographs within this archive acquired by the Museum in 1921.

The cataloguing process is a good excuse to call up from the Archive of Art and Design documents relating to provenance. Oftentimes these include original letters from donors and artists, revealing long forgotten information concerning the acquisition history and its context.

In this case, it was discovered that the Cairo views were part of a larger acquisition from the renowned scholar of Islamic architecture Professor Sir K.A.C. Creswell (1879-1974). Within the file relating to their purchase, is a trove of letters from Creswell documenting his close and long-standing relationship with the Museum.

Creswell is considered the eminent pioneer in the scholarship of medieval Islamic architectural history. Among his publications, Early Muslim Architecture (vol. 1, 1932 & vol. 2, 1940) and Muslim Architecture of Egypt (vol. 1, 1952 & vol. 2, 1959) remain basic research tools for scholars of medieval Islamic architecture.

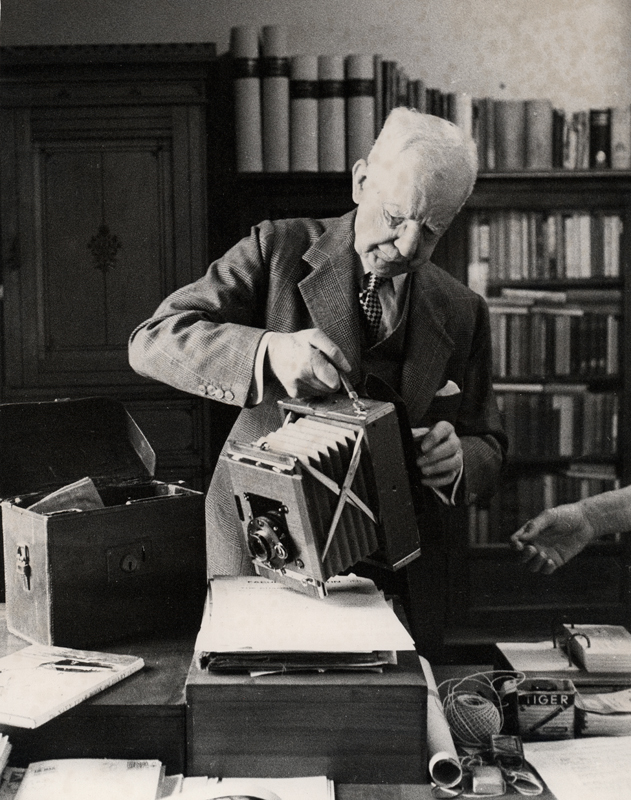

Creswell has been credited with bringing a level of scholarship and quality to the field. Prior to Creswell’s work, archaeological fieldwork consisted of drawing a reconstruction of the original plan of a monument. Creswell considered photography an essential part of recording the physical evidence. He took and printed his own photographs and paid attention to their quality.

The majority of the views acquired by the V&A are of Cairo, but the collection also includes views of Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Tunisia.

1916-21

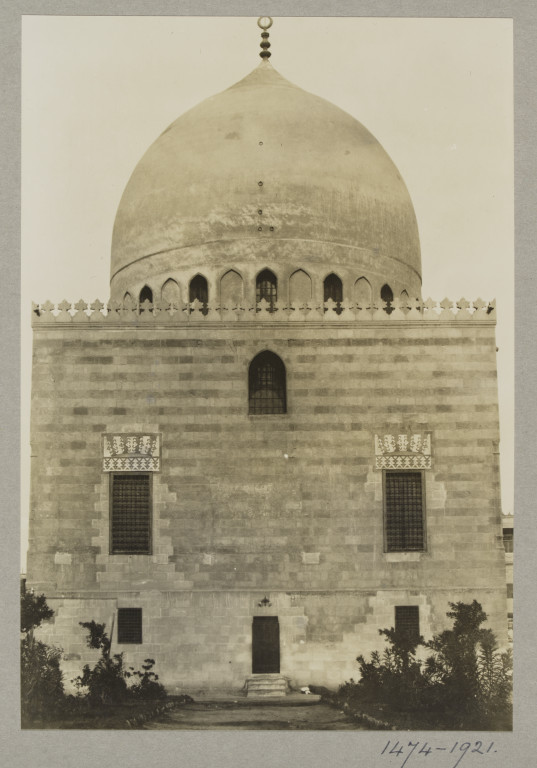

Facade of the Fadawiya Mausoleum, Cairo

gelatin silver print?

Museum no. 1474-1921

1916-21

Northeast entrance of the Mosque of the Emir, Altunbugha al-Mardani, Cairo

Gelatin silver print?

Museum no. 3364-1921

1916-21

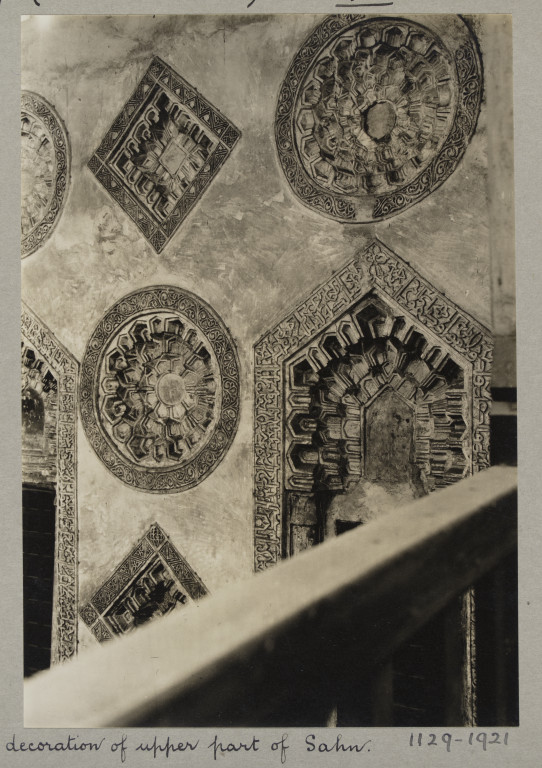

Stucco decoration of the upper part of the sahn of the Mosque of Aslam al-Bahay, Cairo

gelatin silver print?

Museum no. 1129-1921

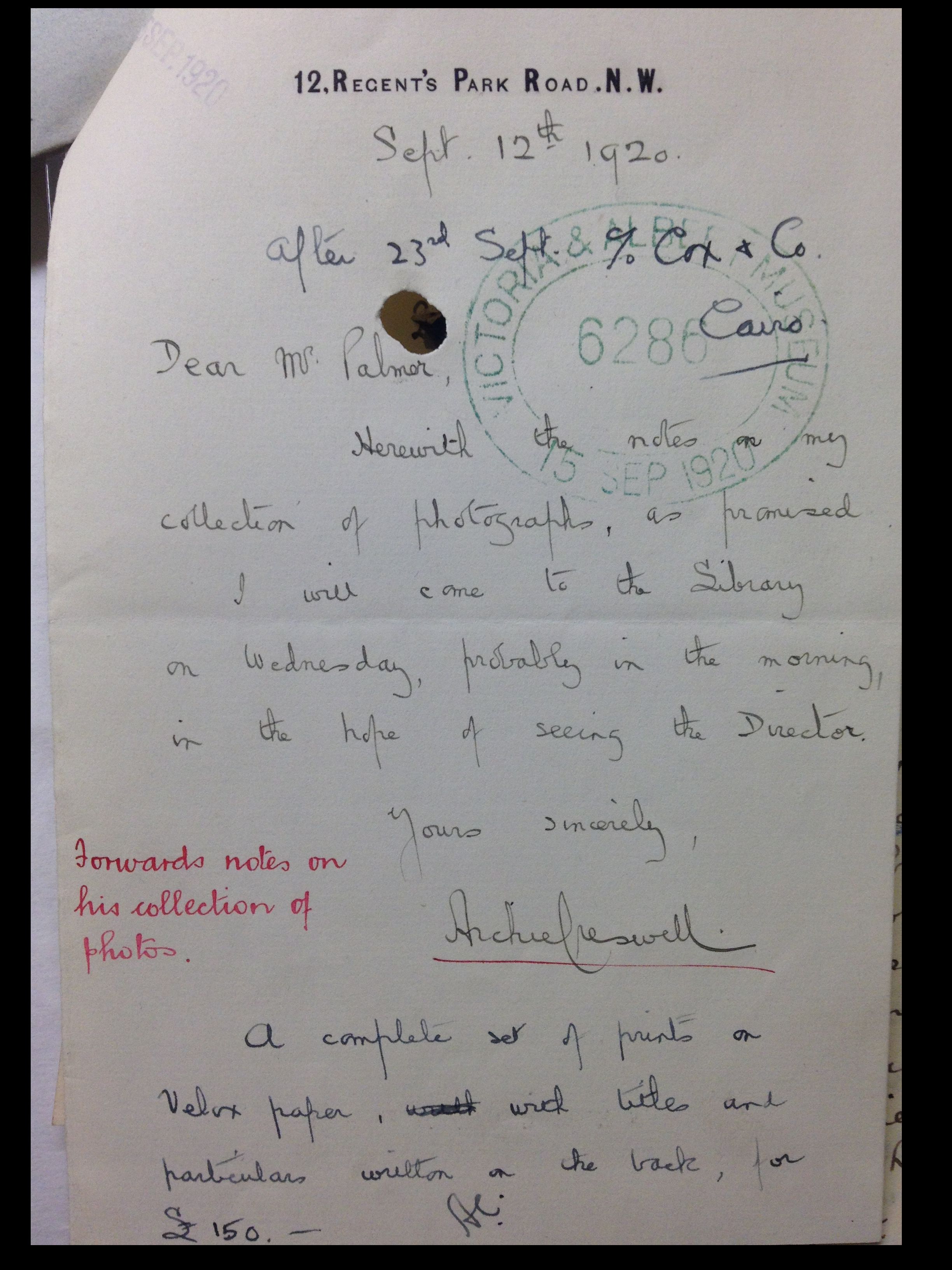

The first record of correspondence between Creswell and the V&A dates from 15 February 1916. It relates to Creswell’s article ‘The History and Evolution of the Dome in Persia’, an illustrated monograph Creswell presented to the Library. Some four years later, Creswell approached the V&A concerning his collection of photographs. In a letter dated 12 September 1920, two months after Creswell was demobilized from the Army – having served in Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Palestine, including a posting as Inspector of Monuments of Occupied Enemy Territory – Creswell wrote to G.H. Palmer, Keeper of the Museum’s Art Library offering a set of ‘about 2600 architectural photographs’ of Islamic architecture, printed on Velox paper. Included with the correspondence were 16 specimen photographs. Noting Creswell’s expertise in the subject and his ‘special opportunities to take photographs’, Palmer endorsed the purchase and the Library confirmed the order on 26 November 1920. This suggests that the V&A was the first public collection to acquire Creswell’s photographs.

AAD MA/1/C3193

While Creswell was known to collect views by other photographers working in the region, it is believed he started taking his own photographs at least as early as 1916, as they were published and credited to Creswell in a 1917 Cairo travel guide written by Henriette Devonshire titled Rambles in Cairo. And in fact, a few of the V&A’s views overlap with those published in Devonshire’s guide, representing some of Creswell’s earliest known photographic output.

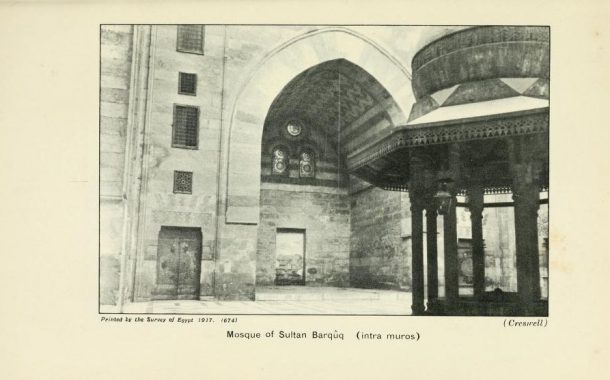

ca. 1916

S.W. Liwan. Interior

gelatin silver print?

Museum no. 1193-1921

Shortly after his offer to the V&A, Creswell departed for Cairo in order to begin his monumental book project on Muslim architecture under the patronage of King Fuad of Egypt. This suggests that the fieldwork Creswell undertook for his book was most likely the source of many of the photographs that he sent to the V&A. This would also explain Creswell’s stipulation expressly limiting the V&A’s reproduction of his photographs pending the publication of his book (the first volume of which did not appear until 1932). It also suggests that the acquisition by the V&A helped Creswell to partially fund his project.

The order confirmed, it was filled in 14 batches sent to the V&A from Cairo beginning 14 January 1921. The last batch was received at the Museum on 26 April 1921. A total of 2612 photographs were delivered by Creswell to the V&A (in addition to the original 16 specimens). Subsequent smaller acquisitions of photographs from Creswell followed in 1926, 1927, 1929, 1930 and 1939.

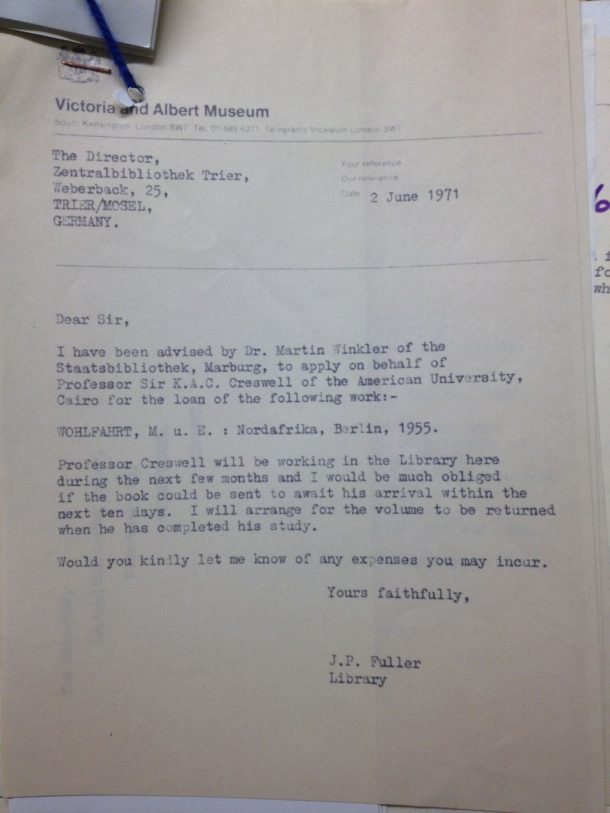

The relationship between Creswell and the V&A extended beyond the supply of photographs. Letters between the Keeper of the Library and Creswell confirm that he was a frequent visitor to the NAL where he conducted research up until the early 1970s. The NAL often communicated with European libraries on Creswell’s behalf, requesting the loan of books for his use at the NAL. In addition, the Archive documents Creswell’s regular gifting of copies of his publications to the NAL, which remain accessible to visiting students and scholars.

2 June 1971

MA/37/5/22

Creswell was also a popular lecturer at the V&A. In regards to a 1931 talk he gave at the Museum, Creswell boasted to his friend, the renowned art historian Bernard Berenson:

“At the V. and A. Museum there is seating accomodation [sic] for 550. At 5.10 there was standing room only, at 5.25 the doors were shut, and MacLagan [V&A Director, 1924-44] tells me that 150 were turned away! So I feel quite like a cinema star! […]”1

Not surprisingly, Curators in our Middle East Section of the Asia Department are keen about this discovery and efforts are already underway to engage their expertise in identifying the views. In the course of the research, we have contacted the Curators of the other major Creswell archives which include the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at Oxford University which holds Creswell’s negatives, both glass and cellulose ; The Harvard Fine Arts Library which has a collection of 2706 Creswell prints in Cambridge and another 2788 vintage prints which are part of the Berenson Archive at Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Florence, Italy; and the Rare Books and Special Collections Library at the American University in Cairo which holds 8000 photographs in the K.A.C. Creswell Photograph Collection of Islamic Architecture . A quick search of the Ashmolean views confirm that there is an overlap with our collection and archivists at the American University collection have also confirmed an overlap.

A puzzling aspect of the Creswell archive is the wide range in tone of many of the photographs, even within the same ‘batch’. At first, it was thought that some of the prints might be albumen, and while this has yet to be discounted completely, the late date of production and Creswell’s statement about Velox paper in the original description he included with his offer to the V&A, points towards gelatin silver prints. Another possibility is that not all the views were produced by Creswell, but also include some produced by other photographers working in the region, which Creswell collected. Further research will include X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectrometry analysis of the views and a detailed look at instances of concordance between the Ashmolean negatives and the V&A’s views in order to determine with certainty the attribution to Creswell for each print.

Below are examples of the range of tones.

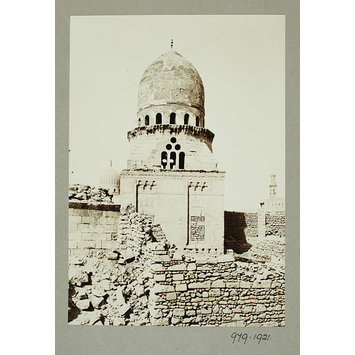

1916-1921

Exterior of the Mausoleum of the Saba Banat, Cairo

gelatin silver print ?

Museum no. 979-1921

1916-1921

Ceiling and cornice of the Madrasa al-Ghanamiya, Cairo

gelatin silver print ?

Museum no. 1180-1921

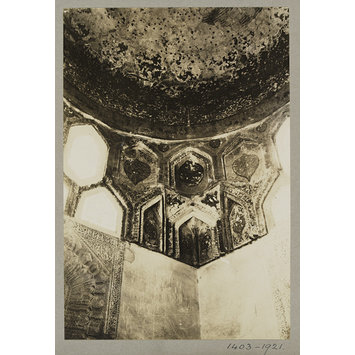

1916-1921

Pendentive in the Mausoleum of the Abbasid Khalifs, Cairo

gelatin silver print?

Museum no. 1403-1921

Many of the buildings which Creswell photographed are no longer extant, others may have been significantly changed through later restoration or adaptation. In light of the recent destruction of cultural sites in the region, these photographs provide an invaluable record for those interested in the history of the major monuments of the Islamic Middle East.

1 Letter from Creswell to Bernard Berenson 5 February 1931, The Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Florence, Italy.