What value do we give to art and more generally to museum objects? Is this value shaped by historic and contextual reasons? How do we know that an object is worthy to be part of a museum? How much is this a choice of museum professionals, and how is this choice affected by the public?

Regardless of the contemporary aesthetic canons and the historical relevance of an object, I believe there is a level of personal appreciation of any work of art, which is mostly related to our personal background. I am an early career heritage scientist, and I recently came across the concept of embodied knowledge,1 and realised that this is the core of my personal attribution of value. I am fascinated with the idea that the objects I study are this sort of ‘information vessel’ and that it is my job to extract and decode this information, so that art historians and conservators can make use of it. The specific meaning of the phrase ’embodied knowledge’ may be different for someone else.

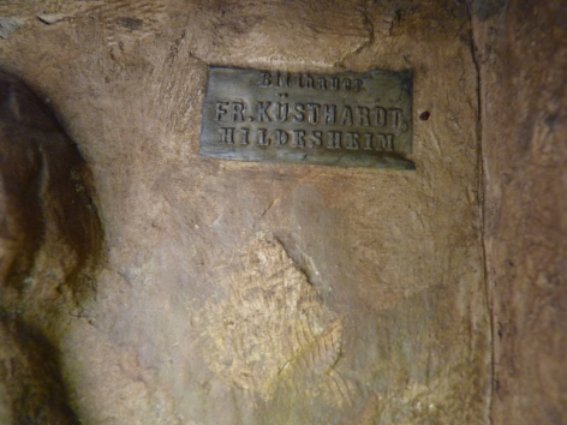

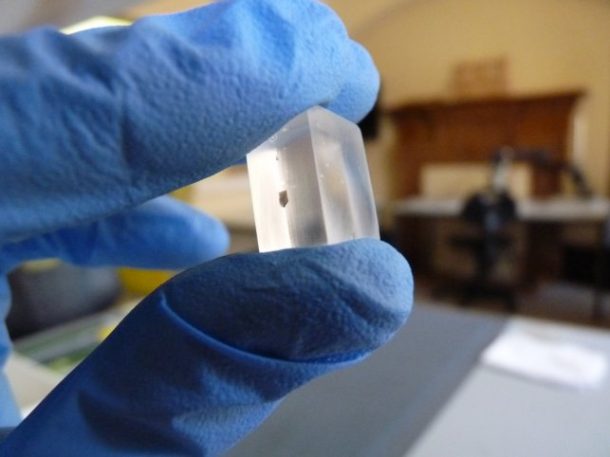

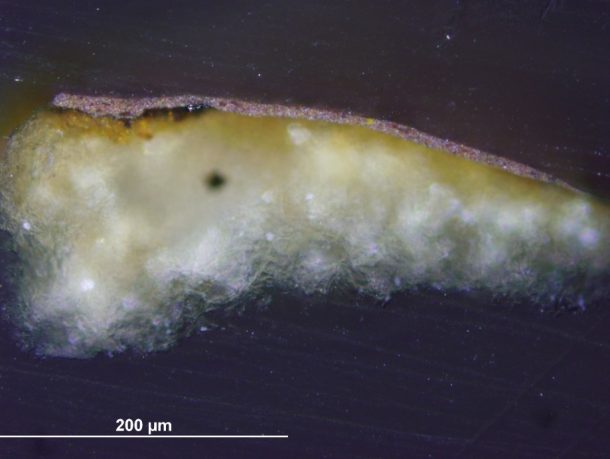

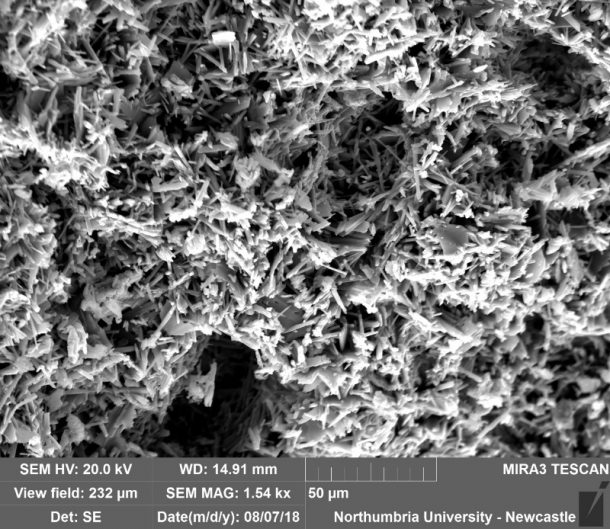

My current PhD project introduced me to the study of historical copies, or replicas, specifically a selection of plaster casts belonging to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The first question people often ask when they find out I’m working with copies is ‘why?’, and I often have to defend the role of these objects in the museum. I study the materials of these 19th-century historical replicas to try to unveil the manufacturing processes used in the workshops at the time. During the Victorian period plaster cast making was a popular and extremely profitable business for various reasons; from educational to decorative purposes, plaster casts were mass-produced and exchanged nationally as well as overseas. Through physical and chemical analysis and by looking at the stratigraphy of the casts I seek to characterise the materials used to produce these objects, and also those applied later to protect and restore them. Cross referencing this information with historical sources, such as 19th-century recipe books and conservation records, helps to understand the presence of a material and eventually to determine the production processes.

This is what is commonly referred to as ‘technical art history’: heritage science is the tool that can unveil and decode the ‘embodied knowledge’ for art historians and conservators. We can then tell stories from the past about manufacturing and Victorian workshops, but also underpin tailor-made conservation procedures.

For more information, see the Cast Courts refurbishment project.