NB: The term ‘negro’ was used historically to describe people of black (sub-Saharan) African heritage but, since the 1960s, has fallen from usage and, increasingly, is considered offensive. The term is repeated here in its original historical context.

As a cataloguer in the Word and Image Department, I always take an opportunity to look in the stores for interesting objects which are currently not on display in the Museum. The Prints and Drawings Study Room closes for two weeks every year to undertake a departmental stock-take. During our most recent stock-take, I came across a box of photographs depicting a variety of African sculptures, taken by photographer Walker Evans.

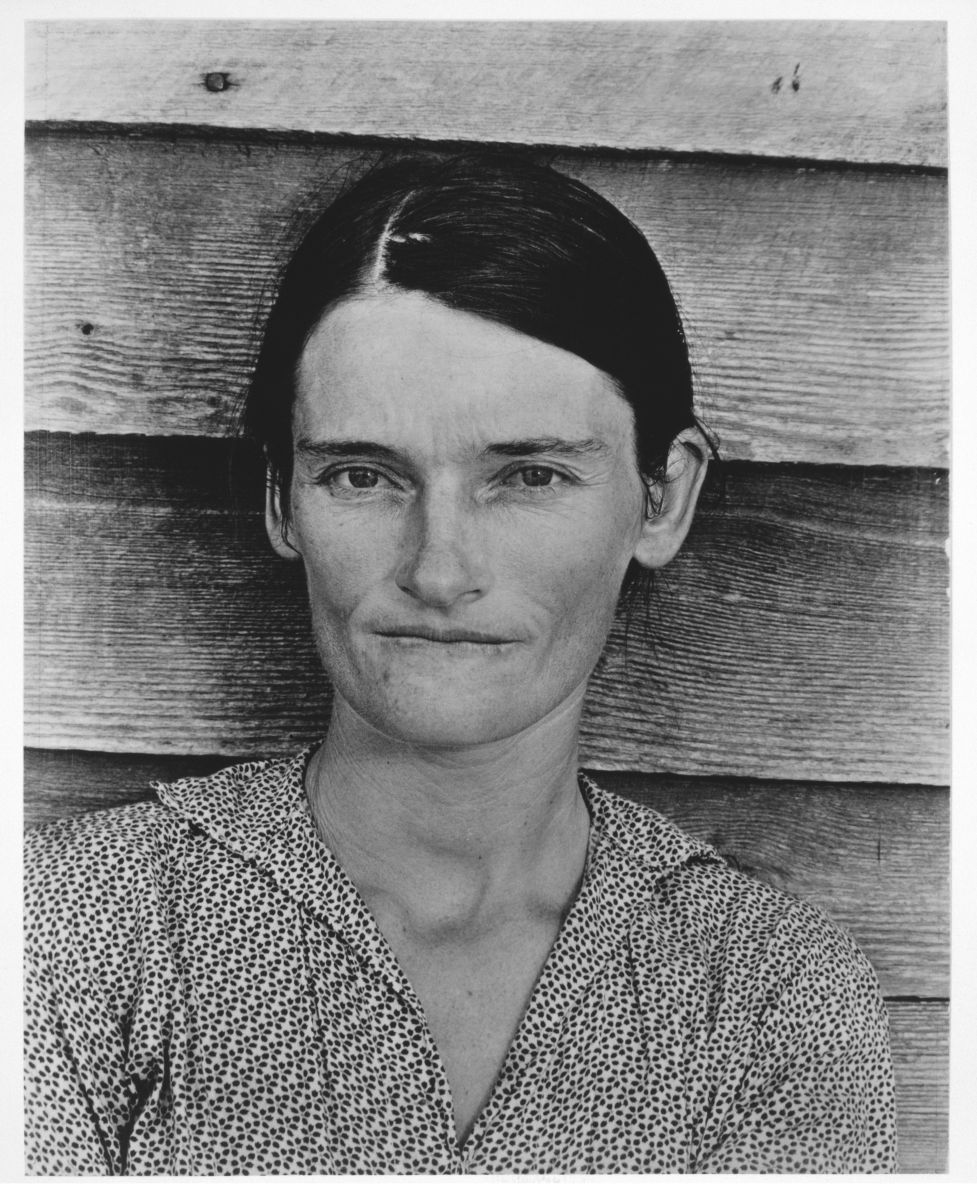

Evans (1903-1975) is best known for his landmark photographic projects documenting the Great Depression in the United States during the 1930s, funded by the US Government’s Resettlement Administration (RA) and Farm Security Administration (FSA). I was keen to discover more about photographs he produced besides these projects, as a leading figure in documentary photography alongside people like Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand.

Evans was approached by the director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Alfred H. Barr, Jr., to photograph over 600 loaned objects which were the focus of the landmark African Negro Art exhibition, curated by James Johnson Sweeney in 1935. Johnson Sweeney was hired as a curator by Barr: he would go on to become the Director of Paintings and Sculpture at MoMA, and later the Director of the Guggenheim Museum.

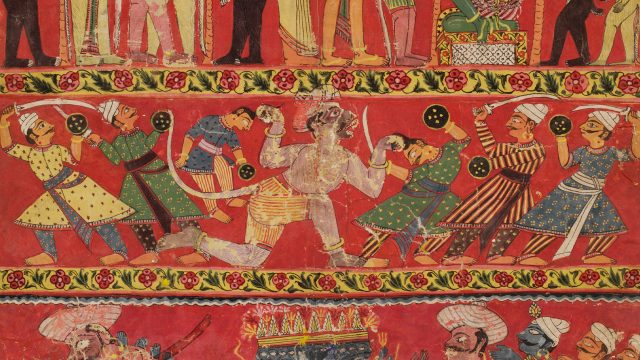

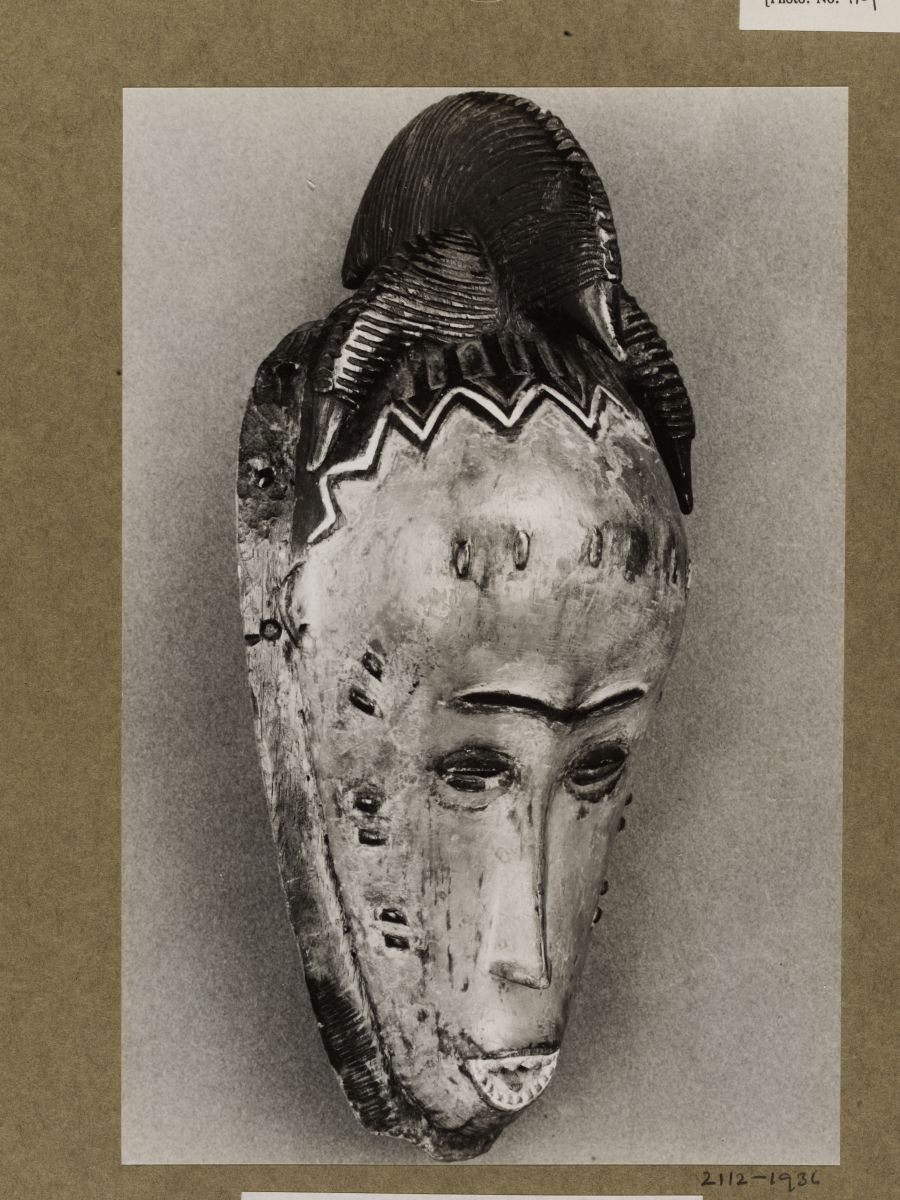

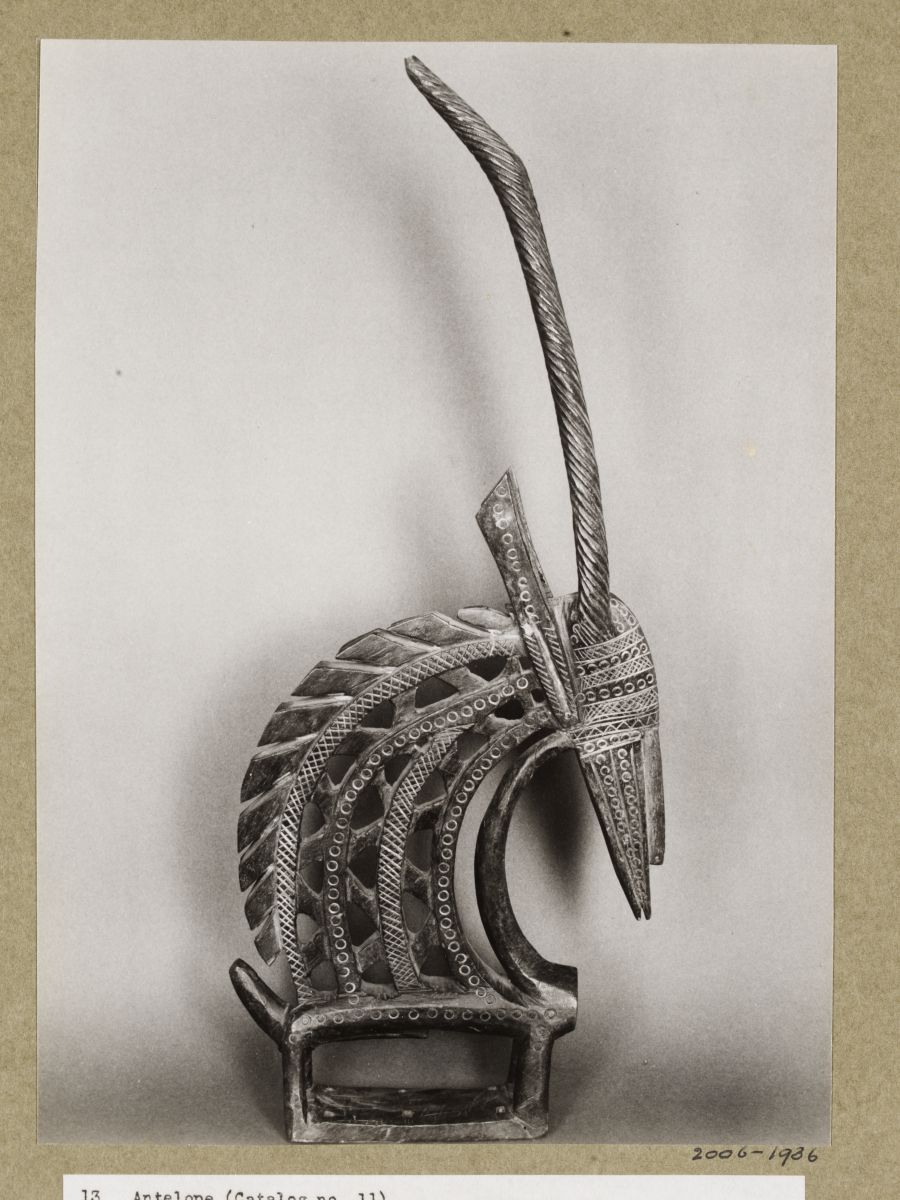

Johnson Sweeney spent 2 months travelling across England, Germany, France and Belgium to arrange object loans from numerous museums and private collectors. The objects chosen – such as masks and fertility idols – highlighted the craftsmanship of wooden and metal sculptures produced in sub-Saharan Africa, with a particular focus on works made in West and Central African countries such as Cameroon, Mali and Burkina Faso. It was difficult for Johnson Sweeney and his colleagues to give precise dates of when the sculptures were made, although rough estimates were given: wooden sculptures were said to have been no more than three hundred years old at the time of the exhibition, while metal sculptures may have been produced prior to the sixteenth century.

Evans was meticulous about the technique he used throughout, ensuring consistency despite the vast task. He spent more than 200 hours photographing the selected objects over a span of several months, with key pieces photographed multiple times from different angles. He fastidiously ensured the photographs were printed and mounted correctly. The exhibition installation was deliberately constructed with a view to place African sculpture in the art historical canon: the set-up of the objects and lighting allowed the abstract compositions to take centre stage.

Using his 8×10 inch view camera, Evans sought to highlight the artistry of the objects alternating between frontal, side and rear profiles, emphasising depth and volume, as well as the detail of the carvings. The sculptures often take up almost the entire frame. Evans would focus closely on the objects, and even cut his negatives before printing. The process of printing, mounting and collating the prints into a catalogue took almost one year in total.

Barr believed education was integral to the ethos of the museum: his desire was for the photographs taken by Evans to be included in a portfolio (the Photographic Corpus of African Negro Art) donated to colleges with large numbers of African-American students such as Spelman College in Atlanta, and public libraries. Other institutions with an interest in African art were then approached to buy the photograph portfolios. The Victoria and Albert Museum paid a fee of $85 for a copy of the portfolio.

In the portfolio catalogue, Johnson Sweeney argued that the ethnographic presentation of works from Africa had previously prevented audiences from appreciating the artistic ‘plastic’ nature of the sculptures – a topic he had discussed at greater length in articles and books such as Plastic Redirections in 20th Century Painting (1934), published a year before his work on the MoMA exhibition. He also made it clear that he felt the wooden sculptures in particular were influential to many European and American artists working in that period. It was a key part of MoMA director Barr’s reasoning that documentation of the exhibition would remain to ensure future generations could understand that the “art of Africa is a sculptor’s art.”

The exhibition became one of the most visited exhibitions at MoMA during that period, with over 30,000 visitors admitted within the first two months of its opening. A touring exhibition of a smaller scale was also organised to travel around the United States for over a year. Meanwhile, the Museum’s attempt at engaging with local African-American communities in New York increased attendance figures by nearly 10%. The press also responded positively, with anecdotes of radical artists and collectors visiting the exhibition in large numbers.

While this body of work is often eclipsed by Evans’s FSA work, it is clear that the photographs for the African Negro Art exhibition are stylistically related to his images of farmers and architecture in the American South. For instance, photographs such as the portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs draw upon similar techniques: the subject takes up the majority of the frame and Evans demonstrates a similar use of perspective.

Walker Evans’s photographs of historic African sculptures remain a key source for African art history scholars and those keen to explore more of Evans’s work. If you would like to see these photographs, visit the Museum’s Prints and Drawings Study Room between 10am-5pm on Tuesday to Friday. More information about access can be found here: https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/study-rooms#prints-drawings-study-room