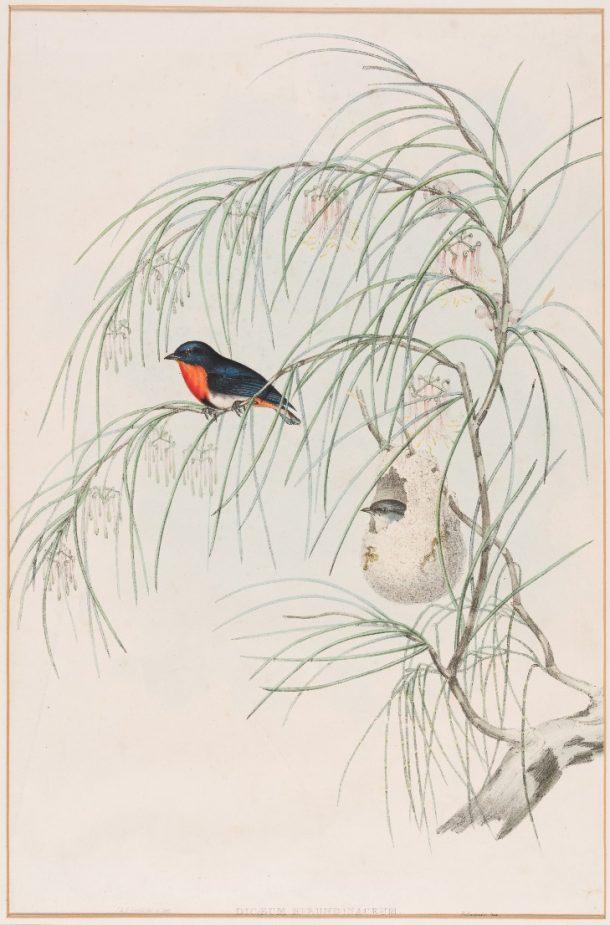

As part of my work on the Factory project, I have catalogued some beautiful illustrated prints of birds held by the V&A, from the ‘Birds of Australia’ series of lithographs produced by John Gould in the 1840s. Much of the information in this blog post comes from Isabella Tree’s fascinating 1991 biography The Ruling Passion of John Gould: A biography of the bird man, available in the National Art Library.

Gould is now known as one of the foremost ornithologists and naturalists of the early Victorian age, but he first became known in Georgian Britain as taxidermist to King George IV, and preserver of the king’s infamous pet giraffe. This extravagant pet was a popular subject with satirists at the time, who ruthlessly mocked the King’s devotion to the animal at the expense of concerns of state. Taxidermy was a lucrative skill in the early 19th century, as it allowed the growing ranks of ornithologists to study birds from all over the globe in close detail for the first time. Despite lacking a formal scientific education, Gould’s work as a taxidermist gave him the chance to enter the growing field of ornithology himself, and he saw an opportunity to create scientific bird illustrations to meet unprecedented demand.

Gould was ambitious for his growing business – wanting to stand out from other bird illustrators, he set his sights on the birds of Australia – on which very little had been published. In his initial studies of Australian birds made in England, Gould relied on the skins of birds he had never seen alive, sent back by explorers. This made it very difficult to envision how the bird would look in life and was a common problem for ornithologists at the time.

Gould soon realised the serious limitations of his method in creating accurate illustrations, and in 1838 he cancelled his previous studies and visited Australia to study the birds from life. Many areas were still unexplored by British naturalists and Gould found it hard to track down the birds, often enlisting an unusual technique that he described in his journal: ‘One successful mode of procuring specimens is by wearing a full plumaged male in the hat, keeping it constantly in motion and concealing the person among the brushes, with the attention of the bird being arrested by the apparent intrusion of its own sex.’ Gould was also disappointed to find that bird populations were heavily depleted by settler activity. Although the British had only been in Australia for only 50 years by the time Gould arrived, the Cape Barren goose had already been hunted almost to extinction (although this did not prevent him shooting a pair himself for study on Isabella island).

In total Gould spent four months in the Outback, sleeping in a tent, under a cart, or ‘more frequently on the ground wrapped in a kangaroo skin rug’. Together with collaborators including the accomplished artist Elizabeth Gould (his wife) and the talented young artist Edward Lear (then a draughtsman at London Zoo), Gould set about producing his illustrations on his return to London. For his publication, Gould chose to use the emerging printing method of lithography, as developed by Charles Hullmandel, who would later go on to print many of Gould’s plates. This technique allowed Gould to cheaply produce large numbers of bird illustrations alongside informative texts – reaching a huge audience.

Looking closely at each print, you can see the names of the different artists inscribed at the lower edge. It is fascinating to see the slight differences in style between each of his contributors – while Elizabeth Gould’s works encompass very fine detail, precision, and a strong eye for colour, the works attributed to Edward Lear give each bird a distinct sense of personality. This created a sense of tension between the scientific mission of Gould’s project and the distinct artistic personalities of his contributors, a tension Lear himself felt keenly, writing after Gould’s death ‘in the earliest phase of his bird drawings he owed everything to his excellent wife and myself’.

Gould published Birds of Australia in seven volumes comprising 600 plates (of which 328 species were named for the first time), with each copy selling for £115, making him a large profit. Although expensive, the publication provided the most complete work ever produced on Australian birdlife, and since then only a few new species have been added, while several are now extinct or nearing extinction. This collection, the product of many contributors, therefore offers an interesting snapshot of colonial exploration of Australia and it’s birdlife in the 19th century, which you can see in the Prints and Drawings Study Room by appointment.

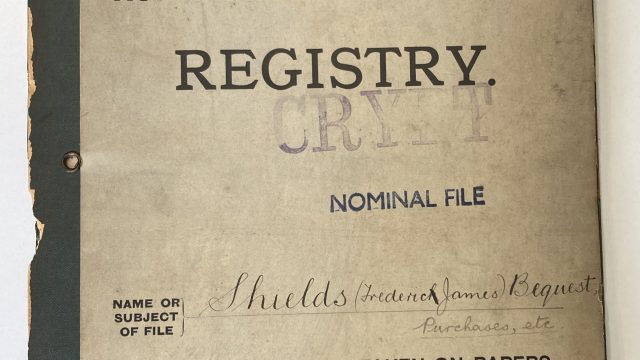

I was very interested to read that John Gould had sketched Australian birds from collections held by the United Service Museum. That museum had opened in 1831 and for several decades it received donations covering a wide variety of materials. A quick look through the museum records reveals a typical entry in 1832 recording the receipt of 32 bird-skins from Australia, presented by The Hon. Miss Courtenay Boyle.

Unfortunately there is no record of the individual species contained in that donation.

In 1858, the United Service Museum revised its collecting policy and decided to dispose of all its Botanical, Zoological and Geological specimens. I have been trying to find out where the USM material went to, but without success. I would be interested to hear if anybody comes across their whereabouts.

A fascinating article highlighting the successful marriage of art and zoology, increasingly important at a time when so many species of all wild life are disappearing. And the colours produced in the 1840’s are really astonishing.