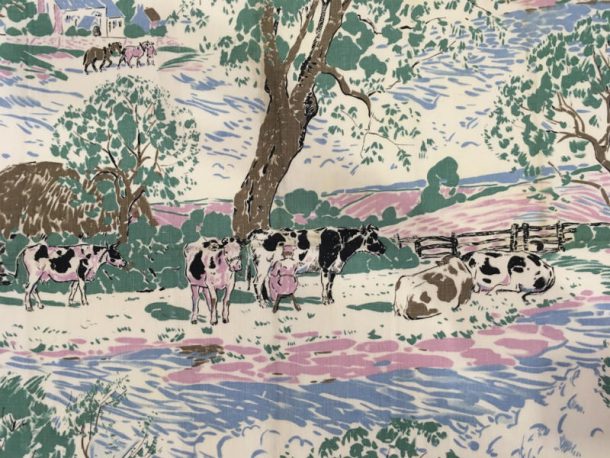

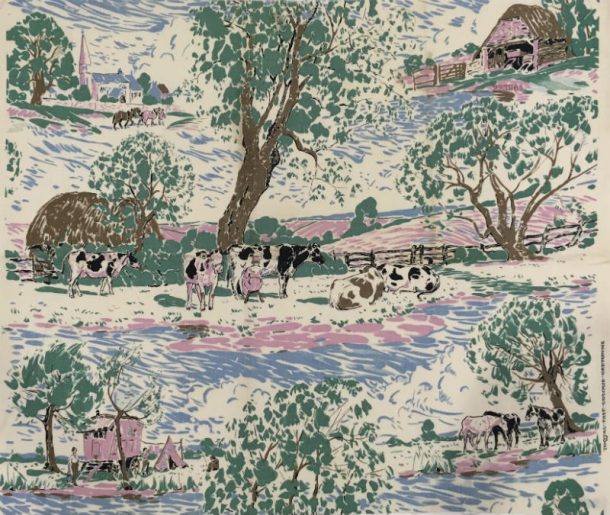

In this blog I’ll be discussing two pieces of fabric in storage at the Clothworkers’ Centre. The first, which features cows and milkmaids, evokes the gift given on the eighth day of Christmas in the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas”: “Eight maids a-milking.”

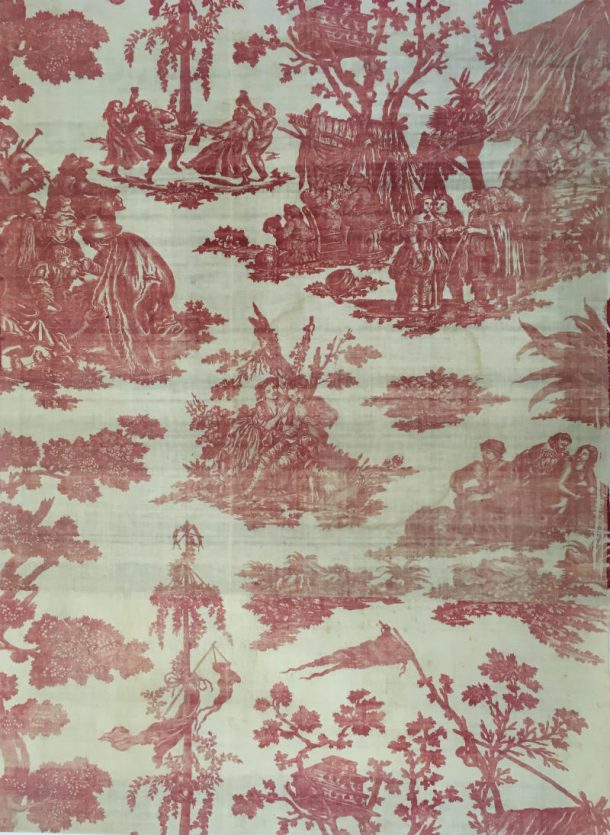

The second object calls to mind the ninth present given in the song—nine dancing Ladies—as it depicts Maypole dancing, amongst other things.

These fabrics are not only united by their connection to this well-known festive song. They both have interesting, if different, relationships with tradition and pastoral life.

The first of these fabrics may have been made in 1925, by Manchester-based company Tootal, Broadhurst, Lee & Co., but it depicts cows being milked by hand—a milking method which had largely disappeared by the start of the twentieth century. The milkmaid’s long dress and head covering also suggest an earlier era. The British 1920s are usually associated with modernity, both generally and in terms of design. Art Deco, a luxurious form of modernism, was particularly popular. Yet this war-torn society, quite understandably, was also eager to escape to the past, and people were particularly drawn to an idealised pastoral past. The relative quiet and traditionalism of the countryside has always appealed to many Brits, but this early twentieth-century interest in the pastoral may also have been connected to the fact that during World War I it was the German strategic bombing campaign, which targeted cities and London in particular, that had the greatest impact on the country itself.

This 1925 design is also antiquated in the sense that it recalls late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century furnishing fabrics depicting a range of repeated scenes—a style which experienced something of a revival around the 1920s. The material in question is, however, more modern than some comparable designs produced by the same company in the same year; various colours have been used instead of the traditional white ground with a design in, say, red or blue.

In terms of the fabric used, while cretonne was not totally outmoded by the 1920s, it was a Victorian material which was largely replaced by chintz around the 1860s.

The second piece of fabric, produced in England around 1770, is less obviously backwards-looking; the activities and garments depicted would not have looked dated in the latter half of the eighteenth century. And it was around this time that fabrics using a number of repeating tableaus were extremely popular. Further, the method used—plate printing—was a new one. Yet the unknown designer, like Tootal, Broadhurst, Lee & Co., was drawn to activities, including Maypole dancing and fortune telling, with ancient roots, and they have likewise escaped to the country, although this was less of leap in the eighteenth century, when Britain was not so urbanised.

This fabric came before, as opposed to after, a period of major unrest—in this case the French Revolution of 1789 to 1799 and the following Napoleonic Wars. Although flights to the past and the pastoral tend to be more pronounced during times of great uncertainty and unhappiness, fabrics like this one can be seen to emphasise the enduring appeal that the past, particularly the pastoral past, has held for designers and customers alike, even in periods of calm, when the attraction is less immediately obvious.

If you’re interested in making an appointment to view textiles and fashion objects at the Clothworkers’ Centre, please email clothworkers@vam.ac.uk.