Poets have long eulogised birdsong – we have Shelley’s Skylark ‘singing hymns unbidden’ and Keats’ Nightingale singing to summer ‘with full-throated ease’ – and the BBC’s Tweet of the Day has been offering a brief daily communion with nature to Radio 4 audiences for several years. But lockdown changed the quality of our attention to this everyday phenomenon. As we worked from home, or adapted to the new regime of furlough, and as we took our permitted daily walks in parks, fields, cemeteries and recreation grounds, birdsong became the common soundtrack to our stilled lives.

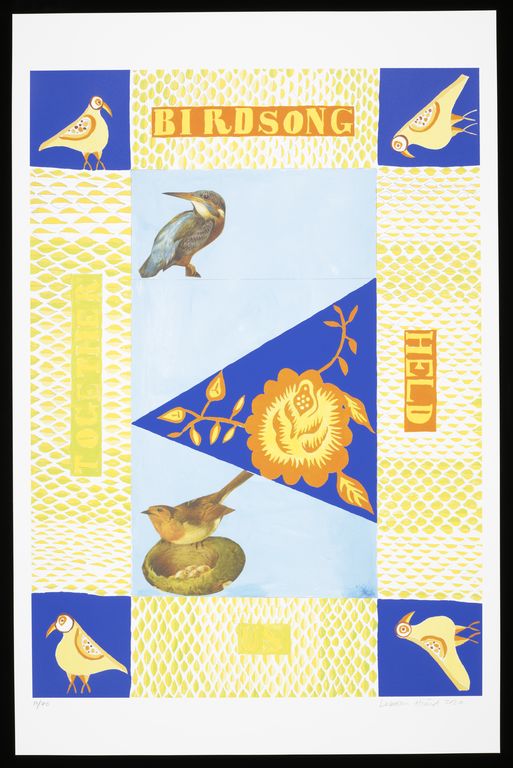

In the unaccustomed quiet we opened our windows or stepped into our gardens and listened. No longer competing with the noise of relentless road traffic, or the roar of planes, the birds sang more clearly, their tones mellifluous, liquid, distinct. Britain’s favourite bird, the robin, and that other garden regular, the blackbird, became familiar welcome voices. Isolated, frustrated, anxious, we found ourselves eager for connection and for shared experiences. For the artist Lubaina Himid, making a lithograph for the Hepworth Wakefield’s School Prints project last year, it was birdsong that ‘held us together’. There is a subtle ambiguity in that phrase, suggesting not only the bonds forged through a shared experience, but also the consolations that joyous life-affirming birdsong offered to those struggling to ‘keep it together’ in the face of grief, loss, loneliness, and uncertainty. Himid described her inspiration:

“Spring 2020 arrived, and all of us were locked in for most of the time. Luckily the weather was good, the sun shone almost every day. We went out, on our own, and walked near sparkling rivers and in among elegant trees, along empty streets and in nearby parks. We encountered people on these outings who we didn’t know but we smiled and greeted them politely. We missed meeting our friends and going out in groups to buy things in familiar shops. Some people felt quite lonely, others didn’t mind too much, but luckily the birdsong held us together.”

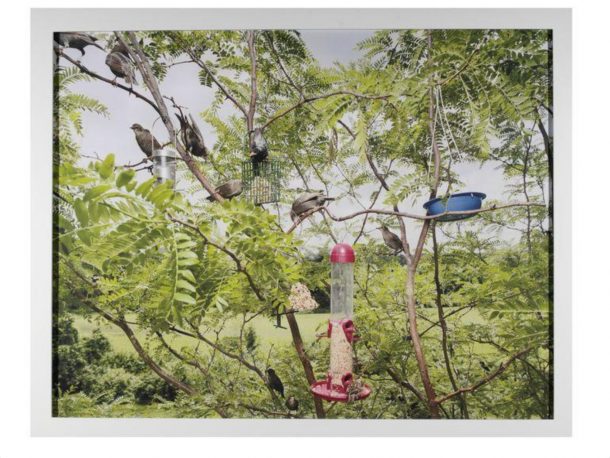

This sense of solace and hope, inspired by birdsong, was widely shared. According to one survey, 63% of people in the UK said that watching birds and listening to birdsong added to their enjoyment of life during the pandemic. A spokesperson for the Wildlife Trusts speculated that “lockdown has meant we are connecting to everyday nature on our doorstep more than ever.” It seems that those of us lucky enough to have a garden were also keen to attract more birds, and sales of bird food and bird feeders rocketed while the RSPB reported that use of their online bird identification tool rose by 95% compared to the same period in 2019.

Birdsong has been the subject of many investigations and research projects – why do they sing and what does it mean? Some songs are specific to mating rituals, as male birds compete to win females; other calls are a defence of territory or a warning of approaching predators. But perhaps birds also sing because they can; maybe they sing for the sheer pleasure of it, as we do. Charles Darwin suggested that birds sing from ‘mere happiness’, and hearing a blackbird in full song, the soft persistent lulling of the wood-pigeon’s coo-COO-coo-coo, the cheerful chattering of sparrows, or even those clever mimics, the starlings, playfully imitating a siren or a car alarm, it is tempting to agree with him.

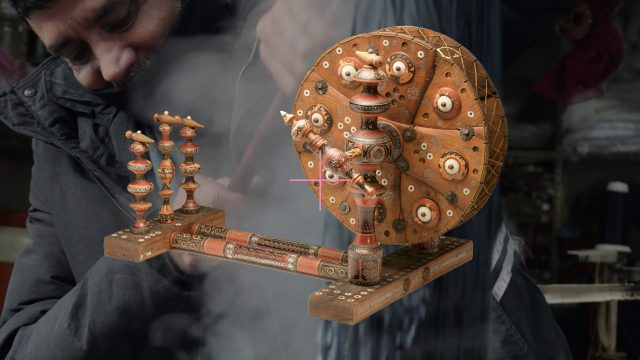

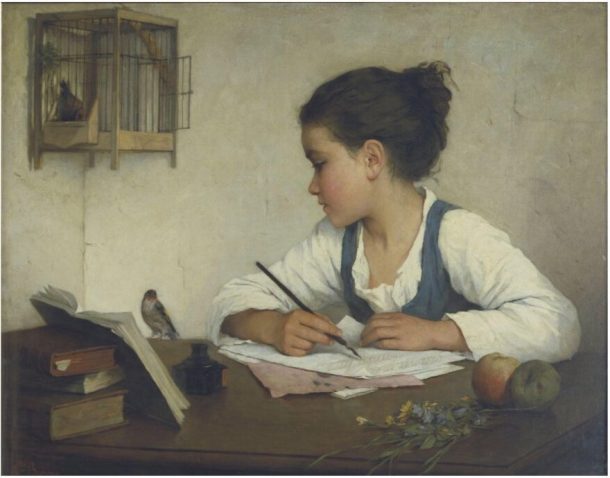

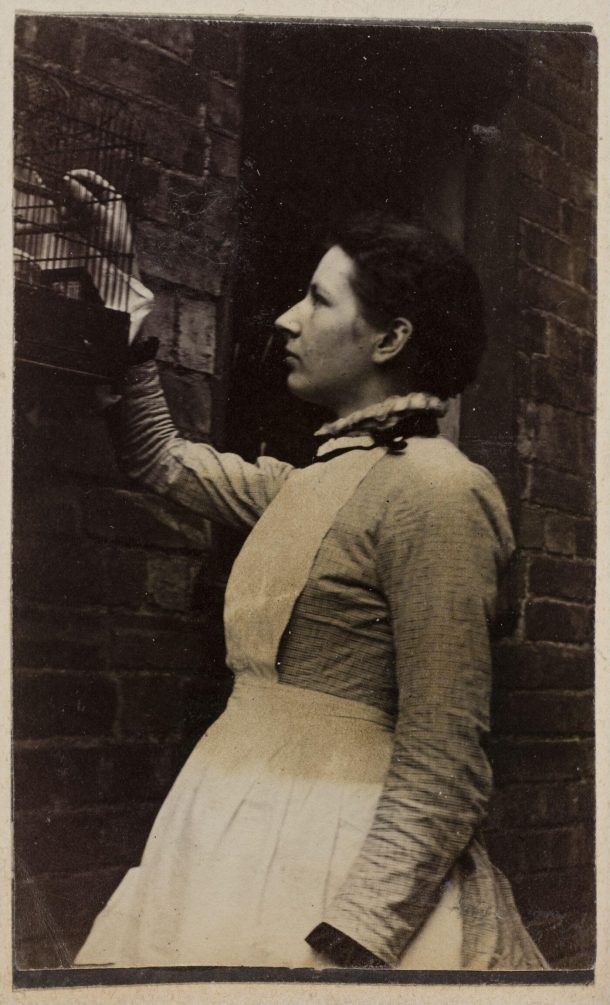

Taking pleasure in birdsong has been a feature of human culture across the world, and amongst all classes. In Victorian England keeping songbirds in cages was commonplace – women and girls kept linnets, goldfinches and wrens as pets, and working men, ‘bird-fanciers’, might enter their birds (linnets, chaffinches) in ‘song contests’ against others. Hand-reared bullfinches were noted for their ability to learn songs taught to them by humans, and ‘whistling bullfinches’ became popular novelties for those who could afford them – apparently Lizzie Siddall, model and muse to the Pre-Raphaelites, owned one, as did Queen Victoria. But attitudes have changed – now the idea of keeping of wild birds in tiny cages is abhorrent to many of us, and we enjoy birdsong because it represents nature unconfined.

Further reading and listening:

‘The earth could hear itself think: how birdsong became the sound of lockdown’, Steven Lovatt, The Guardian, 28 February 2021.

‘Good news! The dawn chorus is louder and clearer than it has been in decades, thanks to lockdown’, Lisa Walden, Country Living, 23 April 2020

‘Bird bath sales soar as the UK stops to notice nature’, Josh Davis, Natural History Museum, 2 September 2020.

Bird Song Identifier, The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/mar/06/birdsong-in-a-time-of-silence-by-steven-lovatt-review-lockdowns-high-notes, PD Smith, The Guardian, 6 March 2021.

‘Victorian cage-bird fanciers of Brick Lane’,London Sound Survey, 6 March 2012.

Tim Birkhead, The Wisdom of Birds: An Illustrated Ornithology (London: Bloomsbury, 2008)

Related objects from the collection:

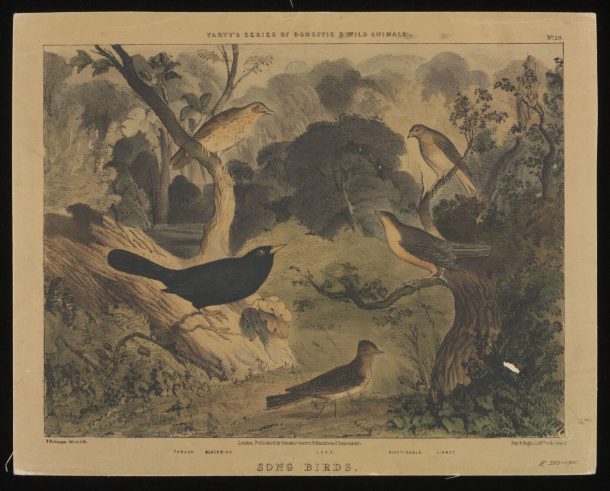

Songbirds, from Varty’s Series of Domestic and Wild Animals, Frederick Robinson (lithograph), UK, 1846 (V&A: E.280-1901)

Sustenance 114, Neeta Madahar (photograph, iris ink-jet print), USA, 2003 (V&A: E.3579-2004)

The Pet Goldfinch, Henriette Browne (oil on canvas), France, about 1870 (V&A: 1083-1886, Dixon Bequest)

Woman Opening a Bird Cage, photographer unknown, (photograph), UK, 1880s (V&A: E.1951:139-1995)

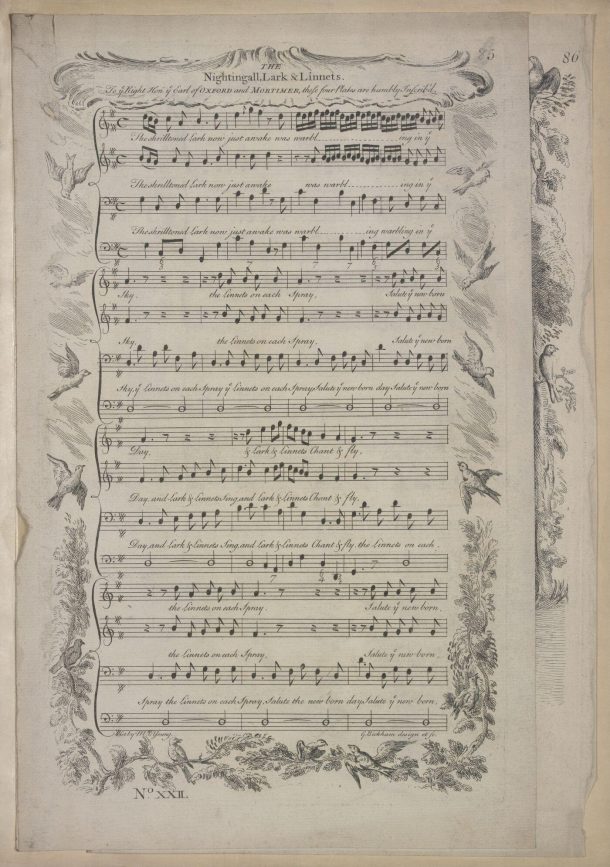

Music sheet for The Nightingall, Lark & Linnets, composer unknown, engraved by George Bickham, UK, 18th century (V&A: S.573-2014)