What have you been watching during the lockdown? We live in an age of streaming media, and with more time on our hands, many of us have turned to these services to fulfil our need for entertainment. Luckily for us we can consume almost any media we want on demand for a small monthly subscription or interspersed with obligatory advertising through a number of different platforms.

You might associate this era of instant gratification through media consumption first with YouTube for short-form homegrown video (launched 2005), Spotify for music (2006), and Netflix for professionally- produced TV and movies (its streaming service began in 2010, although it started in 1997 as a DVD rental-by-post service). But the origins of these platforms have precedents that go back nearly 100 years.

Looking for a proto-streaming service, you could turn to George O. Squier’s 1922 patent for transmission and distribution of signals over electrical lines. His company was designed to pipe music through electrical wires directly into a home receiver, paid for through the electric bill. Named Muzak, it couldn’t compete with the popularity of domestic radio and instead moved into public and commercial spaces. Muzak became synonymous with a particular type of music due to licencing rights and the development of a system called ‘stimulus progression’. This concept suggested that workers and shoppers would respond positively to music with a bright and breezy tone, and that a progressively faster and bouncier rhythm, without the presence of distracting lyrics, would encourage increased productivity.

The content Muzak supplied was, of course, curated and served whole to consumers, even without their tacit agreement. Consumer choice in streaming technology didn’t arrive until the early 2000s. At this point, increased access to computer networks with higher bandwidth, through broadband and mobile technology, had changed the landscape. File sharing sites such as Napster, which used a peer-to-peer network in which consumers could endlessly, freely, illegally share digital files of songs with each other, came to the fore and changed the nature of the music business. No longer were songs goods that could be bought or sold as commodities; instead, they became public goods, that anyone with access to the internet could have for themselves without diminishing access. The record labels grappled to save their business and after a number of court cases, in 2001 Napster finished its peer-to-peer sharing. Instead services such as Spotify developed, in conjunction with licencing deals with major record labels. Offering subscriptions to unlimited music, or limited free music with advertising, Spotify has grown into the foremost music streaming service. Since 2018, music streaming makes more money than the combined sales of physical copies of music and digital downloads.

Like Muzak attempted before, streaming has successfully changed our relationship to recorded music. Many musicians no longer focus on albums as their key artistic statement, and foreground singular streaming successes. In televisual terms, Netflix – which launched its video streaming service in 2011, and thanks to this pandemic, is now more valuable than oil giant ExxonMobil – has been noted for valuing and producing long-form high-production television. Yet, the kind of visionary film making it has been lauded for enabling has become impossible during lockdown, and its successes at this moment are defined through outrageous (and much cheaper) documentaries with viral contingencies (see Tiger King). These platforms also further define and narrow our tastes, encouraging myopic cultural cul-de-sacs through algorithms that point us towards similar attention-sucks, or comfort food in the form of unchallenging retro programming (I for one am gorging on The Simpsons over on Disney+, the streaming service that launched the same week in the UK that many of us started a working-from-home regiment). Is this much different to churning out a kind of piped easy listening as we get on with other tasks?

The other consideration is how this moment affects our future of filmed entertainment. The CGI animated movie Trolls: World Tour recently debuted on streaming services. Originally destined for movie theatres, it instead came straight into our homes (or those with young children… mostly). Is cinema no-longer a shared experience? What does this mean for the future of Hollywood movies? Strikingly, as a film made with computer-generated imagery, with the right technology available to the artists, it could also have been made by a team working remotely from each other in their homes, as many of us are right now. As we wait to see this big-budget animation’s success or otherwise, we have to question, is the solitary home experience of streaming the future of watching, and making, blockbuster entertainment?

This article was originally written on 20 April 2020

Further Reading

- Muzak Headed for Bland, Easy Retirement, Interview with Joseph Lanza, WNYC Studios, 6 February 2013

- Muzak: Stimulus Progression 5 (album), , Nick Perito Orchestra, 1973

- Elevator Going Down: The Story Of Muzak, Luke Baumgarten, Red Bull Music Academy, 27 September 2012.

- Is Trolls: World Tour the Most Important Movie of 2020?, , Steve Rose, 6 April 2020

Related objects from the collection

‘Videosphere’ television set, made by JVC Ltd.

This successful television design from JVC in the 1970s makes explicit the connection between space travel – as popularised by the moon landing – and television consumption. JVC suggest here that surfing the infinite channels of a television is akin to exploring the infinite space of the universe. By 1976, with the introduction of satellite television, the connection between space and television was brought one step closer. Of course today’s streaming television services come through cyberspace rather than outer space.

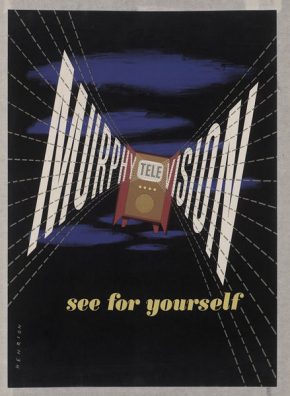

Poster, ‘Murphy Television See for Yourself’, by Frédéruc Henri Kay Henrion

This poster advertisement for Murphy Televisions highlights the early enthusiasm for TV technology in the 1940s, suggesting its potential for limitless content. A television is set over a horizon-less night sky, with radio waves emanating out towards the viewer.

We also run streaming services and were testing a new subscription platform to attract new fans. The problems started to arise when we received our phone bill for the first month. We are just a startup and can’t afford throwing money here and there. So after some talks with other business people during the conference, I decided to try voip phone singapore and their cloud VoIP phone system. Integration was very simple, plus we used a special offer that was small but really appreciated token of customer appreciation from the company. We have already managed to recover about 20% of our subscribers that had already left before. I think the results were good.