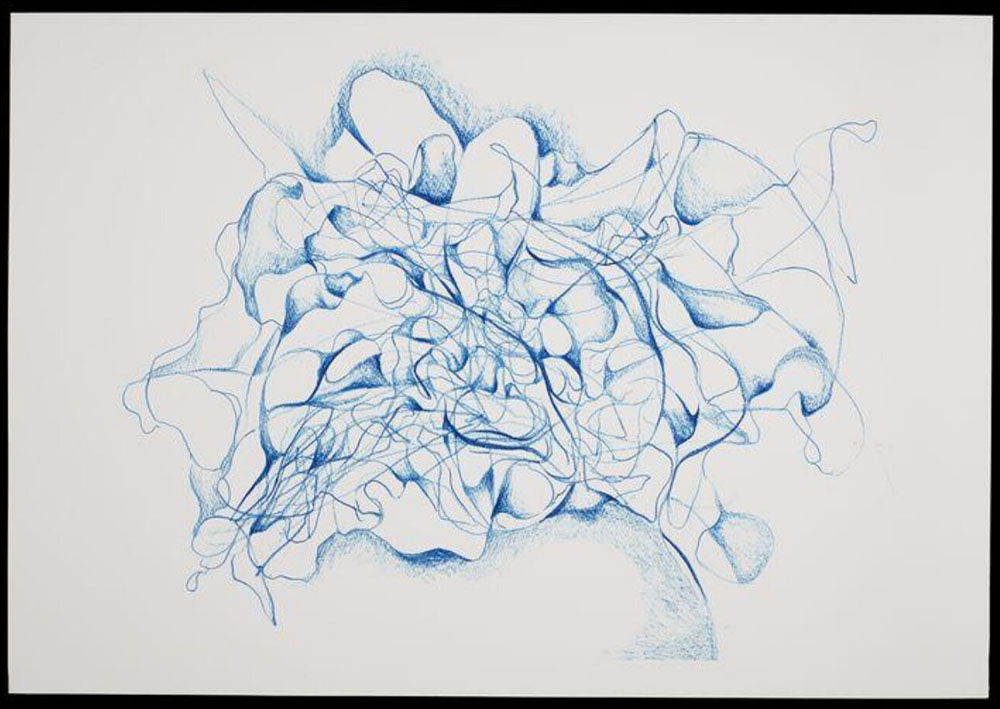

The V&A has recently acquired MEMORY (Drawing Operations Unit Generation 2) by Sougwen Chung. The acquisition of MEMORY comprises a fine art print, a film documenting the artist’s process, and a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model contained within a 3D printed sculpture.

Sougwen Chung is a Chinese-Canadian artist, programmer and researcher who works at the forefront of advanced robotics, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). For the last seven years, she has been developing a series of robot collaborators with which she explores human-machine creativity and the boundaries of kinship and alterity. MEMORY was produced in 2017 and forms part of her ongoing inquiry into computational memory, datasets and the artistic potential of human-robot exchange.

On occasion of the acquisition of MEMORY, I had the opportunity to interview Chung about the work. Speaking to me from her London-based studio, she took me on a journey through the rise of AI in the public consciousness and a questioning of its implications for artists. We discussed performance and the role of time, gesture and colour in her work, and what it means to draw with code. Throughout our conversation, she emphasised a deep preoccupation with ideas of mutual exchange – in part because her artistic practice is defined by collaboration, both with other programmers and researchers, but also with her robotic drawing partners. Named Drawing Operations Unit Generation_X (also known as D.O.U.G.), Chung has been iterating these robotic systems since 2015 in response to her evolving artistic preoccupations.

Katherine Mitchell: To begin, could you introduce us to your robot collaborators, D.O.U.G.?

Sougwen Chung: Back in 2015, I developed a system involving a robotic arm, custom software and an overhead camera that recorded my drawing actions. The camera’s visual input was processed through computer vision software that transformed the visual data into instructions for the robotic arm’s movements. Through this system, the robot would draw alongside me in a live performance, interpreting and responding to my drawing gestures in real-time.

This early exploration of mimicry catalysed my interest in exploring computational and human memory and, in 2017, I developed the second generation, D.O.U.G._2, to probe exactly this. D.O.U.G._2 is trained on a dataset of my own artworks: two decades of archived, digitised and categorised drawings that are interpreted using machine learning technologies in the form of a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). These RNNs are algorithms that are distinguished by their own internal ‘memory’. They hold information from prior data inputs to influence subsequent inputs and outputs. While other machine learning systems process inputs discretely, the RNN’s ‘memory’ supports a greater understanding of sequence and context over time. Through this computational memory, D.O.U.G._2 reinterprets my past drawings and draws with me simultaneously. D.O.U.G._2 is the system I worked with to produce MEMORY.

Why this specific interest in human and computational memory?

The development of D.O.U.G._2 coincided with a watershed moment for AI technologies, not only the development of the specific AI systems used in MEMORY, but also the prominence of AI in the public consciousness and collective speculation on its role in our changing society. I’m deeply interested in how collective and personal histories are captured in datasets, and questions of how these AI systems might come to shape future memory. And for me, creative practice provides the outlet for these inquiries.

D.O.U.G._2 was the first time you drew on your past artistic practice as input to probe these interrelations between personal and computational memory. What was it like to create the drawing dataset – this act of rediscovering, sorting and classifying your past artworks? And how did it feel seeing D.O.U.G.’s interpretations of these?

For me, this process of transforming my drawing archive into a dataset really reinforced how the AI systems are deeply connected to us as humans, our own data, and our own individual ways of processing and mediating this information. And when I first encountered D.O.U.G._2’s interpretations of my past drawings, it did feel like engaging with my own artistic memory from five or six years ago. There are particular ways of mark-making that the robot would return to, in collaboration with me.

But this act was never intended as an automation of the drawing process. Instead, I wanted to introduce an ulterior mode of communication with my past drawing selves through this robotic interpretation. With D.O.U.G._2, drawing becomes less about artistic agency, and more about relation and response.

There’s an immediacy and vulnerability in that unseating of artistic control, and in that unknowing of D.O.U.G.’s interpretation. This is evoked so strongly in your live drawing-performances. When did you introduce a live audience, or begin seeing your drawing as performance?

From the start, it seemed like the most natural thing to do with D.O.U.G._1. But if I were to speculate, I’d say that performance has always been central to my creative life. My background is in classical violin, so I think so much of what I understood about artistic expression was in front of an audience, having that energy of shared experience, and forming these collective audiences and communities.

In the early development stages of D.O.U.G., I invited an audience to witness an unproven system defined by technical errors, bugs, anticipation and possibilities. This sense of unpredictability, and the differing audience reactions of frustration, disappointment and pure delight became a creative catalyst for me.

I do think drawing is an inherently private activity, but despite this, the liveness of performance enabled me to re-establish a human presence that was so important for how I understood creativity. This was something I’d lost in my early interactive and digital art. But with a human presence in the drawing-performances, a sense of alteration and development over time is reinstated – and of course a sense of anticipation and unknowing. All of this is so crucial to how I understand working with D.O.U.G.

So if we think about these drawings as durational, what are the conditions of time? What – or perhaps who –determines the duration of the performance and its conclusion?

Time is quite elastic in the performances. A sense of completion is driven by my intuition really, rather than any programmed conditions of the robot, or other external parameters. I always instinctively know when it’s done. This is usually in the space of optimised human attention, which is around 25 minutes. It took about 25 minutes of focused drawing for the MEMORY collection, but implicitly held within this 25-minute performance is also two decades of my creative practice as memory.

I find that the process of producing the dataset actually flattens time and erases any moments of pause and contemplation. My drawing gestures are transformed into images, which are then transformed into a string of binary data. So for me, performance is key to bringing back those pauses, those moments of silence, and the rhythm of drawing action.

What’s the role of colour in your drawings? Is there a significance to the blue and how these shades persist through the archive of your drawings?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been instinctively drawn to blue. And when machine-readable, the blue hex value reads as a period of around 1970 to 2023. So those dates are nested within the blue colours. For me, this is a way of encoding the colour of this generation as it is machine-readable. So, while D.O.U.G._2 is a lifelong project and the D.O.U.G. series is multi-generational, these colour values really ground the project in a specific moment through a form of steganography – as a hidden message just for the computer. That felt right to me.

In what ways is D.O.U.G._2 a lifelong project, and in what ways is it evolving?

D.O.U.G._2 is a lifelong project because the dataset is continually fed with my new drawings – I’m continually adding to the dataset. While the other generations of D.O.U.G. are rooted in a specific moment, D.O.U.G._2 is a project I keep returning to. And from 2017, the new drawing inputs are already a result of the collaborations. So, at this point, the dataset becomes inextricably intertwined with this exchange, and those recursion elements become more evident, which is really exciting to see.

On this topic of recurrence and iteration, could you reflect on the evolution of your drawing style over time? Has it changed in any significant way since the introduction of D.O.U.G.?

Because I think how I draw has been informed by my early life as a violinist, it’s really about the practice of gesture over image-making. For me, the drawn line is an abstraction of action, rather than intentional image-making. I’m always delighted when people identify a recognisable style, but that artistic imprint and aura in the work is inherent, not intentional. This continues to be a fascinating thing to me about mark-making.

Thinking about your drawing as gesture and embodied action, rather than image-making per se, is really fascinating. I’m wondering if your Chinese heritage plays any role here?

I think it does. Amusingly I found out rather recently that, one of my ancestors in the first generation of Chungs from Hunan was a prominent calligrapher to the emperor. I don’t know what role generational memory plays in these processes. That’s something I’m still trying to unpack. But I do think there’s something about calligraphy, its gestural nature and the way the human accent of the calligrapher is captured in the inscription.

I’m fascinated by the interplay between poetry, form, expression and control in calligraphy. The way that control is used for expressive intent is remarkable to me. But recently I’ve become particularly interested in the radical expressions of the Gutai Art Group. Gutai were a contemporary Japanese art collective whose energetic performance-paintings amplified mark-making to a heightened level of embodied action. For me, Gutai cemented drawing as a whole-body action, with the audience brought into the space of performance. They expanded and really exploded what drawing can be.

This sense of drawing as a whole-body action really intensifies through later generations of D.O.U.G., which is now on the fifth generation. Could you speak more on the further evolution of your work after MEMORY and D.O.U.G._2?

With each generation of D.O.U.G., the project has evolved from mimicry and memory through to multiplicity, spectrality and assembly. The generations after the MEMORY project have interwoven the individual and collective body, and also shifted in scale, moving between the invisible logics of urban crowds in D.O.U.G._3, to the invisible logics of the body’s electrical signals in D.O.U.G._4 and D.O.U.G._5.

In these most recent generations, I’ve been wearing a headset to capture my brain’s electrical activity while performing centring activities including drawing and meditation. My own biofeedback becomes D.O.U.G.’s data input. I found myself meditating a lot during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, and it was during this time that I began to consider the possibilities for other types of gesture that are perhaps not as active or intentional as the drawn line. By abstracting my own being into cognitive states and electrical signals, I’m interested in what it means to draw as and with this essential part of myself, which is manifest as data and then as robotic drawing gesture.

So that’s where D.O.U.G is today. But running through each generation is really a preoccupation with machinic interpretation of human mark-making, movement, energy and intention. The algorithmic gesture is not an automation or a denial of my artistic agency, but an expansion of what the ‘artist’s hand’ is within this exchange. With each new generation of D.O.U.G., I’m continually exploring expanded forms of mark-making, questioning notions of authorship and what it means to co-create with other forms of intelligence.

Sougwen, thanks very much.

Notes

The acquisition of MEMORY comprises a fine art print of the collaborative drawing on paper, a film documenting the artist’s process, and a 3D printed sculpture encasing a USB Flash drive, which contains the image dataset and details of the RNN model used to train D.O.U.G._2. Together with the drawing and film, this data documentation reflects Chung’s total creative process and details the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in contemporary art. Find out more and view MEMORY in Explore the Collections.

With many thanks to Sougwen Chung for agreeing to be interviewed.

When magic and technology becomes one hopefully they shall both be remembered. Great blog excellently written. Good luck with the future projects .