On a bright summer’s day in 2019 Nigerian-American artist Kehinde Wiley stepped out onto the streets of Dalston in search of a particular kind of energy and charisma. Widely known for his highly naturalistic paintings of black men and women set against intricately patterned backgrounds, he had been commissioned by the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow to produce six new, large-scale works for what was to be his first solo exhibition at a public institution in the UK. After developing his unique style of portraiture in Harlem and then touring it to various cities around the globe – from Beijing to Rio de Janeiro, Jerusalem and Lagos – east London was to become the latest setting for his customary ‘street casting’ process, and the place that he would encounter Mojisola Elufowoju, Kaya Palmer, Savannah Essah, Dorinda Essah, Quanna Noble and Melissa Thompson. The resulting portrait of Melissa Thompson has just been acquired by the V&A East team through Stephen Friedman Gallery, with the generous support of Art Fund and Dr Philip da Costa. It will make its way to the V&A this month.

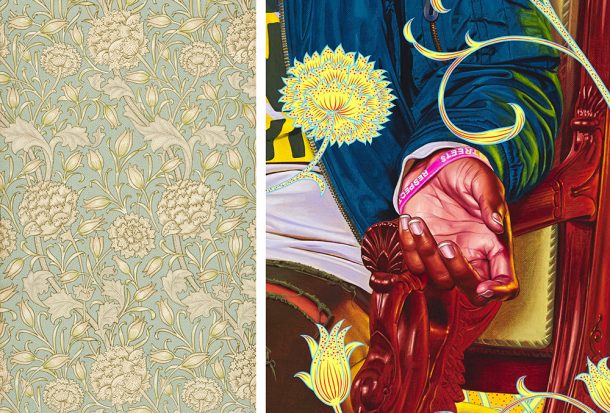

In the painting Melissa Thompson sits in a Regency-style chair in front of a bold, yellow backdrop of William Morris’s ‘Wild Tulip’ design from 1884. With her body facing away and head turned towards the viewer, Melissa’s relaxed, seated pose echoes those of the landed gentry depicted in eighteenth century works of art. The staging is emblematic of Wiley’s longstanding approach to figurative representation, appropriating the formal conventions of historic European and American portraiture in which the power and privilege of the aristocratic are visually endorsed. His African, African-Caribbean and African-Diasporic models assume the poses implicit in these historic depictions of grandeur as they are photographed and transferred diligently to canvas at a larger-than-life scale.

I do it because I want to see people who look like me.

Kehinde Wiley

Having characterised portrait-painting as “a type of marking, a recording of one’s place in the world” in an NPR interview at the beginning of his career, Wiley has since employed this artistic mode as a political act that calls into question the canon’s exclusion of black subjects. In his adoption and disruption of tropes once used almost exclusively to depict white, male subjects, he seeks to elevate the marginalised, challenge perceptions of blackness and raise questions around the politics of identity. In this new series, Wiley was keen to explore the correlations between his longstanding preoccupation with race and class and issues of gender inequality and female autonomy, by drawing upon the acclaimed work of prominent American writer and feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The series’ title ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ is borrowed directly from the text Gilman is most known for – a semi-autobiographical story of a woman confined to a bedroom and driven to mental breakdown as she tries, in defiance of a ‘rest cure’ prescription, to retain her independence and penchant for intellectual work. Written at the close of the nineteenth century, the work was a demand to be understood, acknowledged, and liberated from an unjust, patriarchal society. The book made a huge impression on Wiley when he read it as an art student, recalling in an interview with the Observer last year his fascination with “the sense of powerlessness and sense of invention that happens in a person who’s not seen, who’s not respected and whose sense of autonomy is in question.”

As Gilman’s tale unfolds, her nameless protagonist becomes increasingly fixated on the design of the room’s ‘revolting’ yellow wallpaper, at first identifying ‘a strange, provoking, formless sort of figure, that seems to skulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design.’ Some pages later this figure faintly emerges as ‘a woman stooping down and creeping about behind the pattern.’ It isn’t long before this mysterious female figure begins to grab hold of the pattern and shake it, as if to try and escape her doomed fate. By the end, the ‘torturing’ pattern comes to fully symbolise not only the protagonist’s personal sense of entrapment, but the patriarchal resistance faced by many women at the time in their plight for independence and self-definition.

She is all the time trying to climb through. But nobody could climb through that pattern – it strangles so…

Beyond engaging the tropes of historic portraiture and referencing the work of Gilman, Wiley further samples from the past in his contemporary reimagining of wallpapers produced by Morris & Co in the late 19th Century. Having encountered the designs (and those inspired by them) in the second-hand furnishings bought and sold by his mother as he was growing up, the work of Walthamstow-born designer and social reformer William Morris has been a continual reference point for his practice. Throughout his career, Wiley has consistently paired his sumptuous rendering of individuals with bold and ornately patterned backdrops. These have served chiefly to divorce each subject from a specific place and time, producing a contextual ambiguity that locates the figures strictly within the decorative. Here, in his visual response to ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ the Morris & Co. designs are deliberately and playfully appropriated to bring to bear further layers of meaning.

Rendered in a palette of vivid – and at times lurid – yellows, Wiley has allowed curling tendrils to break free of the rationally ordered Morris & Co. backdrops and roam into the space of his female subjects. This collapsing of the figure-ground relationship echoes Gilman’s descriptions of the increasingly fraught relationship between her protagonist and the wallpaper’s sprawling design. But the women in Wiley’s version are not ‘skulking’ or ‘creeping’ behind the pattern; they are not strangled or struggling to break free. They are powerful emblems of strength and autonomy, depicted as if just-emerging out of the foliage, as if breaking through the patterns of invisibility and oppression which society has replicated – like a wallpaper repeat – over and over again. These east Londoners stand proud and defiant among the flower motifs; resolute, empowered and wholly deserving of such sublime representation.

On its arrival at the museum Wiley’s portrait of Melissa Thompson will be prepared for display in the V&A’s British Galleries at South Kensington. Here, visitors will see it alongside the work of William Morris and his contemporaries, as well as an embroidery design by his daughter May Morris – an accomplished artisan in her own right and coincidentally, a collaborator and friend of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Two of Morris’s original colourways for the ‘Wild Tulip’ design will also be displayed.

The painting’s eventual display in the collection galleries of V&A East’s forthcoming Museum at Stratford Waterfront we hope will inspire contemplation and conversation around issues of identity, power, privilege and belonging for many years to come. Wiley’s appetite for generating provocative collisions between the past and present, the local and global, art history and street culture, will be particularly pertinent within the new museum’s transhistorical displays, in which the V&A’s historic collections will be activated by the voices of makers from across the globe to confront contemporary concerns. Further to this, we hope that the portrait of Melissa Thompson will offer a hopeful and affirming message with regards to the representational role of the museum – one which eradicates feelings of alienation and exclusion like those Wiley personally felt whilst visiting art museums as a young man. Struck by the absence of people of colour on the walls of these institutions, Wiley has since directed his life’s work towards countering such processes of erasure, using his creative practice to construct new and inclusive narratives of power and agency. These vital ambitions are a perfect fit for the new kind of institution we want to create at V&A East and, as such, Kehinde Wiley has been on our radar for some time. Happily for us, east London has been on his.

Awesome painting art…..