A major focus of The Fabric of India is on the making of Indian textiles, and dyeing has been a key part of that process for thousands of years. Indigo is the dye most often associated with India, and the dye and the country were so inseparable in the ancient world that the Greeks named the dye after the country, giving us the English word ‘indigo’. Indigo was grown and used in many parts of South Asia before its replacement with synthetic versions in the 1890s, and a huge range of indigo-dyed textiles survive, from this deep blue cotton dress (left) from Kohat, in today’s North-West frontier Province of Pakistan, to fine slate-blue muslins from Srikakulam (formerly Chicacole) in Tamil Nadu.

Not all the blues in India are indigo. In the north-eastern states of Assam and Nagaland, a leafy plant known in English as Assam Indigo, in Latin as Strobilanthes cusea, in Assamese rum and in Naga osak yields a range of dark and light blues, depending partly on how shady or sunny a spot the plant grew in (see the Naga shawl, right).

Yellow dyes come from a huge number of plant sources in South Asia, but all of them are fugitive – that is, they fade when exposed to light or are water-soluble so they disappear with washing. India’s most renowned yellow dye is turmeric (also used in cooking), which gives a wonderfully rich yellow as in this patolu from Patan, Gujarat (below left).

As we want to be quite sure we are identifying dyes correctly in the exhibition, we have been sending samples to institutions in Boston and Brussels which have the technology and the expertise to analyse tiny fragments of thread to identify the dye used.

This has been incredibly useful both in confirming assumptions we had made based on the geographical origin of a piece – for example, identifying red chay-root dye in a chintz from South-East India – and also in giving us completely new information, such as that the beautiful yellow pitambhar dhoti from Varanasi (above right) was dyed with Delphinium barbatum (yellow larkspur), a dye known throughout Central Asia and North India as Isparak.

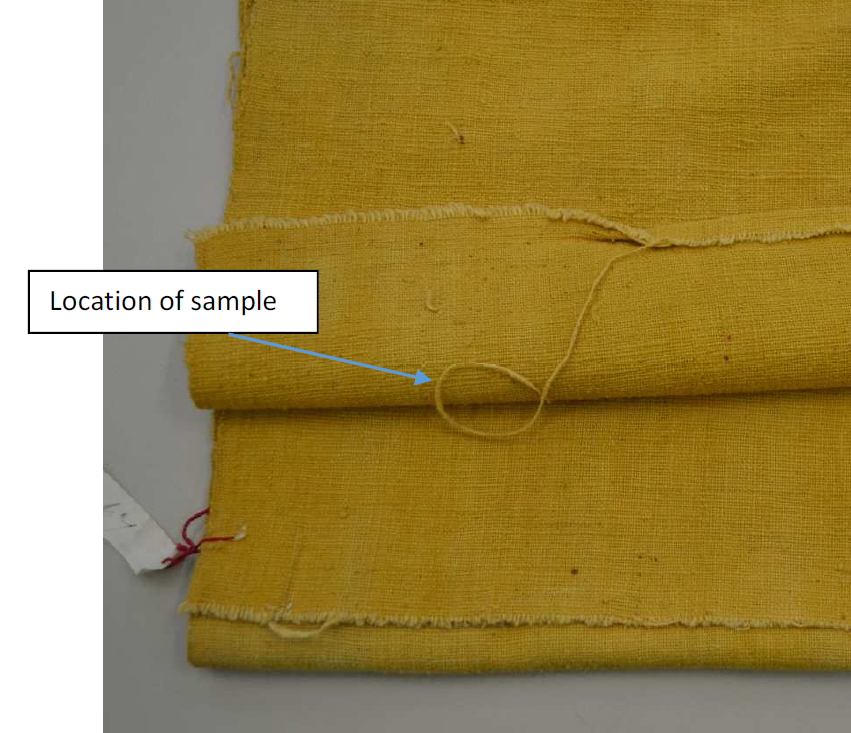

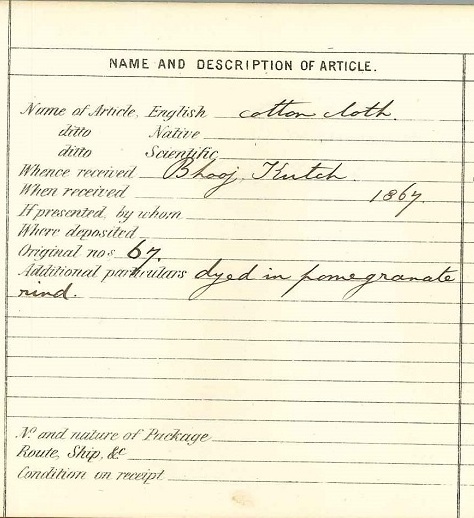

In some cases, we are lucky enough to have information about dyes in the original accession information, such as the note for the humble yellow cotton length (below left) which is noted as ‘dyed with pomegranate rind’, as well as the very useful information that it comes from Bhuj in Kutch.

Red dyes are as quintessentially Indian as indigo, and often have auspicious associations with marriage and fertility. The world-renowned chintzes which were exported to Europe from the 17th century onwards owed their desirability to their fast, bright blues and reds, produced by indigo and chay-root, a plant that is native to coastal South-East India (and the northern tip of Sri Lanka) which gives a range of beautiful reds and pinks on cotton when combined with an alum mordant (left).

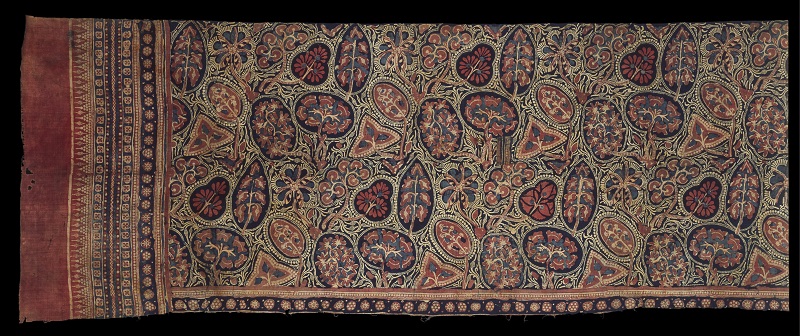

Members of the madder (rubia) family are traditionally used more in North and West India, and have been identified for example in the 14th-century Gujarati block-printed cotton textiles sent to Indonesia (below).

Perhaps the most beautiful of the Indian reds is produced by lac, although the process of extracting it is not for the squeamish: it comes from the crushed bodies, eggs and larvae of female lac insects which settle in large masses on the branches of certain trees, especially in eastern India and Assam. Used on silk, it produces a pinkish-red when used on its own (below left), and a brilliant, deeper red when used with a mordant (below right).

Wonderful post, beautiful pictures. Love the yellow colour achieved using pomegranate rind. I have travelled across Rajasthan and Gujarat rooting out beautiful textiles, block-printers and dyers, embroiderers, etc. and your post takes me right back there. Looking forward to your exhibition immensely. If you would like any Indian embroidery workshops to run alongside – have a look at my website.

Have enjoyed immensely reading your article. Running a textile enterprise out of New Delhi, I’m very much looking forward to the exhibition at the V&A next year…!

Thank you for posting this, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. I’ve always had a love for Indian textiles and can’t wait for next year’s The Fabric of India exhibition.

Lovely post – but just to put the record straight, indigo dye comes from many different plant species – whether woad, a Polygonum, an Indigofera, ‘Strobilanthes (now re-named) or others. I cover all this in my book ‘Indigo: Egyptian mummies to blue jeans’ (British Museum Press) by the way…

.

Very informative. Yellow also comes from Har Shringar flowers and Kesu flowers and geru. It tends towards the orange I feel. Look forward to the exhibition. I think it should be a travelling one and should grace the Indian shores also. I am passionate about Handicrafts from India especially hand made textiles (woven, dyed and embroidered) and write extensively on it.

WOW ! Thanks for complete fabric dying information. I am looking for information for my Handloom Startup. Once again thanks for such a quality information .

Very informative.

Very informative

Simply lovely. Great to know a bit more about India’s textile heritage. I hope young people will preserve it by wearing handlooms, instead of switching to western clothing.

Very informative research and article. Khmer lac results in a more pinkish red, so I am surprised that the lac yielded such a bright red with the mordant. Very interesting!

Very informative