We’ve all been a little over excited this week in the build up to a certain surprise. When Jonathan Lim took his girlfriend Sunhye Moon to see ‘Wedding Dresses 1775-2014’ on Thursday afternoon, little did she know she’d be leaving the exhibition as a bride to be.

Jonathan had really done his research, and had already come to the exhibition before he discussed how and where he’d like to propose with Exhibitions Assistant Mary Linkins and I. Sunhye is a Graphic Designer with a strong interest in art and the couple often come to the V&A together (we were voted the Most Romantic Museum, after all…). Jonathan ‘wanted to make the V&A part of an important life event for us as it has provided us with lots of cultural learning and enjoyment’ – and what better spot could there be than with a backdrop of wonderful wedding dresses?

With their romance fresh in our minds, this seemed like a good week to explore the history of proposals and engagements through the time period of our exhibition.

Despite the boom in literature with a romantic lilt in the eighteenth century, it is a truth universally acknowledged that marriages have not always been made for love. The reality of most betrothals and engagements at that time was much more pragmatic. A proposal, and whether it was made, accepted or refused, was a family decision based on the social and financial credentials of each side of the couple. Formalised even further than this, for a couple to become engaged their families would negotiate a legal contract which established the financial arrangements on which the marriage would be conducted. If a betrothal broke down at the settlement stage it would damage a woman’s reputation, so until the deal was done, public discussion of the engagement was best avoided. As a result, while the completion of these negotiations might drag on for months, once the terms were agreed, a marriage might take place almost immediately – in some cases, within hours, in many, within the same month.

In the 19th century, these contracts continued to be an important preliminary for engagements. However, the Married Woman’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which gave a wife the right to own, buy and sell her separate property and keep her earnings, changed that. If a woman’s property was legally her own, its transference and size need not be negotiated for the benefit of her bridegroom. With the removal of one of the tensest aspects of betrothal and courtship, arguably the opportunity for romance and individualism in engagements grew.

In stark contrast to the eighteenth-century brides whose negotiations had to be handled quietly, the engagements of society brides of the early twentieth century were eagerly analysed in endless newspaper gossip columns. Rather than tainting her chances, the fact that Margaret Whigham had already broken a first engagement fed the excitement over her second to Charles Sweeny in 1933. Meanwhile, when Maud Cecil became engaged to Greville Steel in 1927, the press coverage was extremely high. The Sketch celebrated with a front page photograph of Maud, declaring her a ‘charming bride to be’.

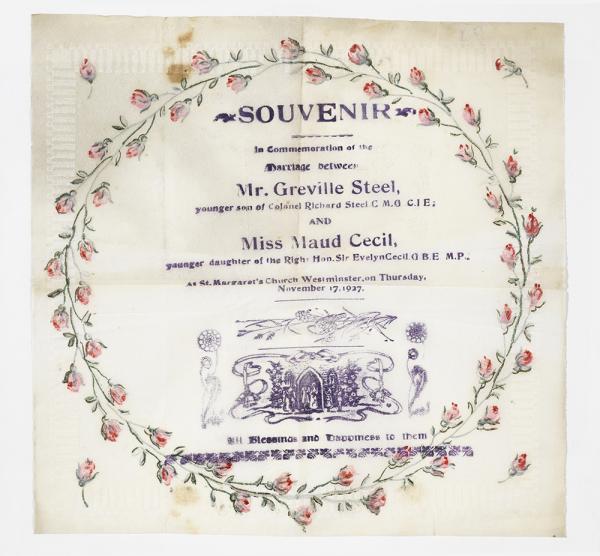

As this interest in their engagements made celebrities of brides to be, Maud was prepared for the many well-wishers who crowded outside St Margaret’s Church in Westminster on her wedding day. To give them a memento of the day and to thank them for their support, souvenir napkins, printed with the details of the wedding, were handed out to the crowd. Fantastically, one of these napkins survives, and we have it on display in the exhibition as a symbol of the furore these engagements and marriages inspired.

Modern proposals tend to fall into two camps – either, a discreet discussion between a couple in which they mutually agree to the next big step, or some idiosyncratic gesture, romantic and reflective of the relationship involved. Crucially, in the majority of cases the decision is made independently by the couple, not as a familial group. Contemporary proposals tend, therefore, to be highly personal and are sometimes the only private part of the preparations for a modern marriage. Weddings are the public celebration and cementation of an earlier, private decision for two people to share their lives together, and the proposal is the expression of that decision. With this in mind, and not wishing to intrude, we made a point of not asking our exhibition brides how they got engaged. However, it was brilliant to have a real bride to be in amongst our wedding dresses, another reminder of the real and emotional stories our displays represent. It was a great to play a part in Sunhye and Jonathan’s special moment, and we offer them our congratulations and wish them every success in their life together.