The V&A has recently been gifted the archive of the renowned product designer Sir Kenneth Grange, a leading figure in the international design world for over 70 years. Throughout his prolific career, Grange has often been described as modernising the domestic life of Britain, and is known for pushing the limits of design, with products that are beautifully made, exceptionally well-engineered and a joy to use. He has worked for leading brands including Kenwood, Kodak and Parker and has designed an extraordinary range of products including the London taxi, a shopping basket for Boots chemist, and the first modern razor. His archive will go on display at the V&A East Storehouse when it opens to the public in 2024. In the BBC Two series Secrets of the Museum viewers get a sneak preview of the display, as Christopher Marsden (Senior Archivist), Benjamin Brown (Senior Technician), Sir Kenneth and I meet to discuss his career.

I had a chat with Sir Kenneth to further discuss his work and the objects in his archive:

The museum is so grateful that you have decided to give your archive to us. It will be a fantastic and popular resource for visitors to study and enjoy. For readers who don’t know your work, could you summarise what your archive includes?

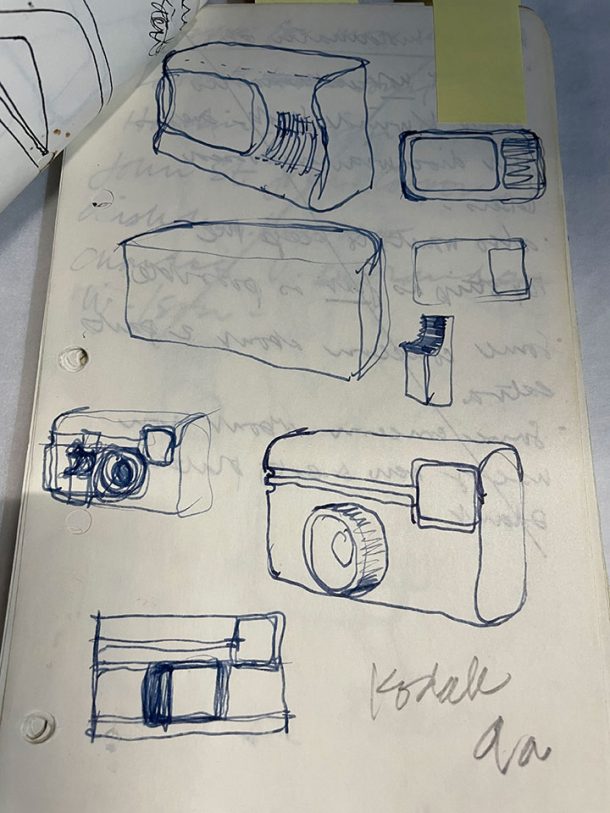

Well, it’s like a diary. I started the habit of keeping a diary from way back. I think my first pages and scribbles in notebooks date back to when I was 12 or 13 years old, and from that time on I have used my notebooks and diaries for as long as I can remember. Then what happened was that by pure accident every time I moved, I moved to a bigger place and so never had to do a big clear out, and by default this meant that I’ve kept every diary or notebook I’ve ever had. It’s a very happy coincidence that means that together the diaries, the models and products that I worked on form a diary of a man’s working life. It obviously contains a lot of personal references, but it’s mainly about the work which I started to get into when I was 13 or 14. And so really my archive is the simple accident of a diary. A diary that is here made up of words and things – things I’d had a hand in creating.

What does it mean to you that your archive is now part of the V&A’s collection?

A broad range of society and social circumstances is reflected in the immensity of the V&A’s collection, and to have even a little place in that is hugely flattering and indeed humbling. I have been fortunate enough to work with many organisations on a wide variety of products and so my archive includes a broad scope that I hope can be a useful tool for people to investigate and learn about society and product design. Future generations will be sure to continue looking back in order to learn from past benefits and mistakes. And so by placing my archive in a public institution, it is my hope that my work can aid in this process. How my archive stayed together is a tale of happy coincidence and my own ‘accidental’ hoarding, but this means that one can now see 80 years of evidence of both my own development, as well as broader societal and design changes in my archive.

How did you become a designer?

I’m of an age where repair was commonplace, and you’d never think of not repairing something, be it your bicycle or your trousers. Whatever it was, it was repairable and that makes a big difference to a person’s outlook. Inevitably, as a small boy I must have started to learn how things were made, as I was in the process of repairing them. Understanding how things are made has been a preoccupation of mine ever since.

I’m also a war-time child and at the outbreak of war my father, who was a policeman, was moved across London from Aldgate to Wembley and the family followed. This change altered my education dramatically, as we moved from one education authority to another. As such instead of staying with what would probably have been a more classical education, I was moved to a much more forward-thinking school that prioritised making and creativity, and so I owe a lot to that happy accident.

You have often been described as a pioneer of user-centered design, and throughout your career you have concentrated on designing products according to their purpose and function, ensuring that they are always a pleasure to use. Why, in your opinion, is it so important that form follows function and what, for you, makes good, responsible design?

I come from a school of thought that relies upon understanding the problem in order to go ahead and do something about it. To that extent the function is where you start and then the form just follows it. And happily, it so often does, so the two often tie in very neatly for me.

You have to be pleased to own something and be happy that you have it whatever it is, be it a pair of old socks, a hat or a handbag. In the moment you pick it up you must be pleased to do it. I think there is great reward in going through a day enjoying everything that you are using. These things then become important and personal, and you don’t want to lose them. Be it a pen or a notebook or whatever, they become reliable friends. The marvellous thing about our world is that it can be very rewarding even at the most modest level.

Can you tell me about a favourite product that you’ve worked on?

This work is at its most rewarding when you are working as part of a bigger enterprise because nobody can ever truly invent something on their own. The enjoyment comes from a big variety of people and skills working together. This is the case for the most elementary thing that you can fashion and create with your own fingers, up to something like a bridge, where you are just a very small player in a big game.

For example, the British Rail High Speed Train – InterCity 125 is still one of my favourite participations. I was the designer of some parts of it and happily for me the media latched onto these areas and so I got the credit for it. But in fact, my part was a tiny part of the whole thing, and it was so rewarding to be part of a team working and cooperating on something like the train. It’s like being part of a football team. In one moment, you can be the star, but you are only there because of the other ten people on the field. The sum of the parts is greater than the whole, there’s no doubt about it.

Another favourite commission and one of my most successful designs was the Kodak Instamatic camera 55x. The basic invention was brilliant and was a breakthrough which made loading film into a personal camera much simpler and more straightforward. My role was to decide what visual characteristic this new camera would have, and I felt it should owe something to the long history of photography. The most expensive camera at the time was the Leica Camera – it had a particular shape to it that had become the definitive shape and way of using a camera. This new camera I was designing for Kodak owed its lineage to the Leica and is how the shape came about.

I also did a tiny, commissioned thing that I try to use as often as I can, and that’s an ice cream scoop. It’s made from one piece of material and is therefore very inexpensive to make. Scooping out ice cream can be quite an arduous task if you set about a well frozen block too early, and so the force of your yield has to be very great. Therefore, the scoop has to be both very comfortable to use and a real extension of your strength. Any hand tool can be best described as having to magnify your own strength, skill or dexterity. The scoop is very primitive, and I’ve probably never designed something quite so simplistic, and yet every time I use it, I look at it with a little bit of pride. I can also use it to scoop out some putty or filler in the workshop so it’s a scoop for all times!

The V&A East Storehouse will revolutionise access to the museum’s collection, making objects in storage visible and accessible to everybody, providing further opportunities for a much wider audience to access, encounter, and be inspired by the collection. Where do you look to for inspiration and how might you use a resource like the V&A’s collection to inform your own work?

I trained as an architect and although I never qualified, it was the place that I grew up. My basic canvas as it were is a lot to do with architecture and I have followed the modernist movement like day follows night. I have spent a lot of time learning about the intricate details of architectural history, as well as the interpretations of architecture and the purpose of a building. Something I am particularly interested in is what sort of buildings do we need today to live in and enjoy that best serve our purpose? But where to go to explore this and other design questions of this nature? The best thing to do is to look objectively at historic examples around us to think about what could have been done differently or better. A collection like that of the V&A can help us answer these questions and creates a terrific opportunity to ask penetrating and wide-ranging questions.

What would your advice be to young designers entering and working in the profession today?

Enjoy making things and really being the owner of the knowledge of how things are made, because it’s really a fascinating study and your bit of the finished thing is often just a matter of style. There’s nothing dishonourable about that, but it’s not the purpose of the thing. So, if you look objectively quite a lot of things could be very different. Young designers should be more and more questioning of the inherent construction of stuff around you.

One of my favourite things to do when I speak to students is to ask them if they know how everything in the room was made. I think it’s a very honourable pursuit in life understanding how things are made.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am very fortunate to have worked with the lighting company Anglepoise for some time now, and it’s a really fascinating territory of exploration. I am kept quite busy with them, and I can’t move for something needing repairing at home, so I spend a lot of time in the workshop too. Very often by just being a bit witty you’d be surprised how often you can find yet another solution to a little problem. A lot of people might call that being creative – and really, it’s in all of us, it’s just a question of whether or not you are encouraged to have that attitude.

A designer on a par with Dieter Rams. Shamefully under celebrated in the UK.