Photography within museums is most often understood through the lens of art history, as a creative or aesthetic practice. Yet, photography also functions as a crucial institutional instrument—an apparatus through which museums and institutions document, classify, and disseminate knowledge.

The history of museum photography undertaken not for artistic display, but to sustain the daily operations of collecting, cataloguing, teaching, and exchange, is a history written in men’s names, focusing on Roger Fenton at the British Museum or Charles Thurston Thompson at the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). Yet hidden in plain sight within the archives of Europe’s great institutions such as the V&A, the Louvre and the Prado is evidence that women were also shaping the visual culture of these museums.

My doctoral research, Armour and Lace: Women Photographers in 19th-Century Institutions, seeks to recover the women whose professional labour underpinned these practices and to reveal how their contributions shaped the visual culture of the modern museum.

Looking for women in the frame

The project began in the V&A’s archives, where more than 150,000 19th-century photographs are listed in the historic accession registers. Among them, I identified nearly 8,000 made by women. I found that most of these women were independent professionals photographing in institutions.

What united them was not style or subject but circumstance: all operated within the new bureaucracies of institutions that were formalising knowledge through photography. These institutions—repositories of art, science, and empire—needed images to catalogue, teach, and circulate objects. Women supplied that labour.

Their stories had been hiding in plain sight, buried in accession registers, ledgers, guard books and in dusty dark corners of overlooked museum storage spaces. Bringing them forward meant reading familiar sources differently—asking, for instance, who signed the negative, who received the payment, under whose name is the patent or copyright, and even who lived in the museum residences. Once those questions were asked, women began to appear everywhere.

Work, marriage, and professional identity

In some cases, the economic vulnerability resulting from widowhood, also paradoxically, opened doors. This was aided through family connections to the institutions they served. Isabel Agnes Cowper, for example, after the death of her husband in 1860, started working with her brother, Charles Thurston Thompson, the V&A’s Official Museum Photographer. When Thurston Thompson subsequently died in 1868, Cowper leveraged her familial networks and took on his role. She and her four children were soon recorded living at ‘3 The Residences’ at the museum, blurring distinctions between domestic and professional space.

Cowper went on to run the museum’s photographic studio for 23 years, producing thousands of images that documented everything from antique lace to monumental plaster casts. While her labour, recorded in the museum’s correspondence, was compensated on a per piece basis – her employment was steady, technical, and essential. Yet her authorship was rarely acknowledged in an archive organised by object rather than maker, erasing her contribution even as it preserved her labour.

Jane Clifford, also a widow, worked in Madrid documenting treasures in the Spanish Royal Collection (now the Prado). Exploiting her deceased husband Charles Clifford’s reputation as photographer to the Spanish Royal Family, Clifford was commissioned by John Charles Robinson, the V&A’s renowned curator. Letters between Clifford and the V&A show her negotiating fees and delivery schedules. She was paid for her expertise in the same way her male peers were, yet her authorship was long absorbed into that of her husband – until evidence in the archives separated their professional identities.

This tension between visibility and invisibility runs throughout the history of women’s institutional photography. Many were known to their contemporaries – paid, sometimes publicly praised – but their identities faded as institutional credit replaced individual attribution. Recognising their names today allows us to see not only what they made but the institutional structures that made their obscurity possible.

Marital status was not the only social determinant shaping women’s photographic careers. Class mattered too. These photographers were middle-class women, many with artistic training. They operated as professionals – submitting invoices, launching publishing ventures, and corresponding with curators and directors.

Louise Laffon in Paris, for instance, photographed the celebrated Campana Collection in the 1860s at the Musée Napoléon III (now the Louvre). She monetised her institutional access and sold her meticulous albumen prints to collectors and educational institutions through subscriptions. Archival payment records reveal state acquisitions of her photographs—proof that her work was not a hobby but a business.

By tracing payments, contracts, and copyright deposits, the picture changes: women were earning livelihoods from institutional photography, operating within networks of exchange that linked science, art, and education across Europe.

Photographing science

While some women photographed sculpture and decorative arts, others turned their lenses toward scientific subjects. K. Marian Reynolds, working for London’s Natural History Museum and the Royal Institution in the 1890s, produced images of bird eggs, laboratory interiors, and Faraday’s experimental apparatus. Her correspondence with museum and institutional officials reveals a high regard for her skill documenting displays.

Reynolds’s photographs were later used in scientific lectures and publications, situating her within the visual infrastructure of knowledge production. Yet she was seldom credited. Her case demonstrates how women’s intellectual labour in science was often refracted through institutional anonymity.

At the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, Alice Everett, Edith Rix, and Annie Russell worked as ‘computers’ and ‘observers,’ photographing the stars for the Carte-du-Ciel project. Their tasks—precise, repetitive, technical—anticipated the data-processing roles women would occupy in twentieth-century computing. Like Cowper, Laffon, Clifford and Reynolds, they were anonymous professionals embedded in the machinery of institutional research.

Art, but also documents

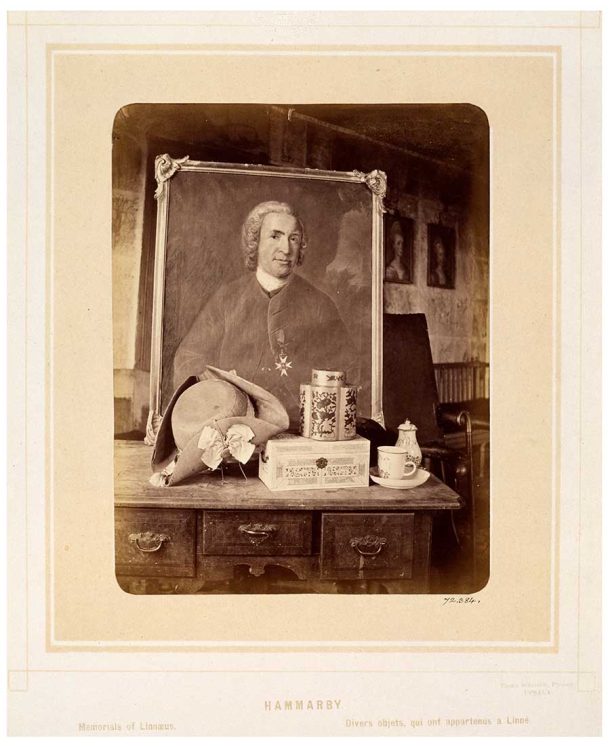

My analysis found that the definition of 19th-century institutional photographer is complex and demonstrates the need to question contemporary definitions of art photography in 19th-century institutions. I looked at the celebrated photographer Julia Margaret Cameron known for her conviction that photography was an art form. Yet, Cameron supplied photographs to the V&A to be used as pedagogical tools categorised as ‘Studies for artists’. Similarly, Swede Emma Schenson’s nostalgic views of places and things associated with the archive of botanist Carl Linnaeus, were accessioned into the V&A collection as examples of ‘Nordic architecture’. In both cases, these women contributed works that blurred the boundary between ‘art’ and ‘document’.

Visibility and circulation

One of the central questions in my research was how these women’s images moved through institutional and public space. Once produced, a museum photograph entered complex systems of circulation: one print might be mounted in a reference album, another used by a design school, a third reproduced in an illustrated book. Their photographs circulated internationally through exchanges between museums and later within the commercial image economy that flourished with the advent of photomechanical printing techniques. Each reproduction multiplied its reach while erasing its maker. The photograph’s authority grew as the photographer’s name disappeared. It’s a pattern that echoes the broader taxonomies of 19th-century institutions, which valued collective authorship over individual identity.

Why these histories matter

As photography historians Elizabeth Edwards and Ella Ravilious remind us, institutions are ‘places where objects are assembled and become knowledge.’ The women who photographed those objects participated directly in that process. Their work shaped how generations encountered art and science: students learning from V&A catalogues illustrated with Cowper’s photographs, scientists studying Reynolds’s images of specimens, or manufacturers, artists and designers gaining inspiration from Clifford’s record of royal treasures. These photographs were never just records; they were instruments of pedagogy and imagination.

Abigail Solomon-Godeau has written that invoking the photographer’s gender is not about evaluating artistic quality but about revealing ‘that however occluded or ignored, women have always been part of photographic history as both players in and agents of its developments.’ That insight captures what I found in the archives: women were not exceptions to the rule but integral to the evolution of photography within modern institutions.

Up until recently, 19th-century women photographers were often cast as genteel ‘lady’ amateurs. Excavating these professional women’s narratives does more than fill historical gaps in the history of photography, it also addresses similar gaps in institutional histories and more broadly, the history of women’s labour. Today, as the V&A and the Parasol Foundation Women in Photography project seek to expand the stories we tell about photographic practice, the lives of Laffon, Clifford, Cowper, Reynolds, Cameron, Everett, Rix, Russell, and Schenson (and I found others!) represent a different kind of professional success than that measured by art historical methodologies, highlighting women’s role producing and communicating knowledge.

Dr Erika Lederman is a photographic historian and cataloguer of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her doctoral research, ‘Armour and Lace: Women Photographers in Nineteenth-Century Institutions,’ was completed at De Montfort University in 2023 under an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award Scheme with the V&A.