The V&A’s display ‘Another Russia: Post-Soviet Printmaking’ features work made by Russian artists after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 when art was no longer strictly controlled by the government. For most of the 20th century, art in Russia was used for propaganda and expressing the ideology of the state. In the 1920s, when the Soviet Union was arising from the ferment of the 1917 revolution, printing was an extremely important tool in defining the new society that was sweeping away many old ways of living and thinking. The poster ‘Friends – Enemies’ by Dmitry Moor is a fascinating example.

The artist Dmitry Moor’s career began in 1907 providing satirical images of tsarist ministers. He continued working in a variety of journals during the 1920s including ‘Pravda’ (Truth), the official newspaper of the Communist Party, and another called ‘Bezbozhnik’ (The Godless) – a natural fit for the atheist Moor. After the revolution he began to design posters, including some of the defining images associated with the civil war of 1917-22 enthusing people to join the Red Army of the Bolsheviks. As you can see on this work he includes his name on his posters, something few were brave enough to do during such a volatile period. His striking images were influenced by brightly-coloured 19th century Russian popular prints called luboks, and similarly captured ideas in simple, often vibrant and striking images.

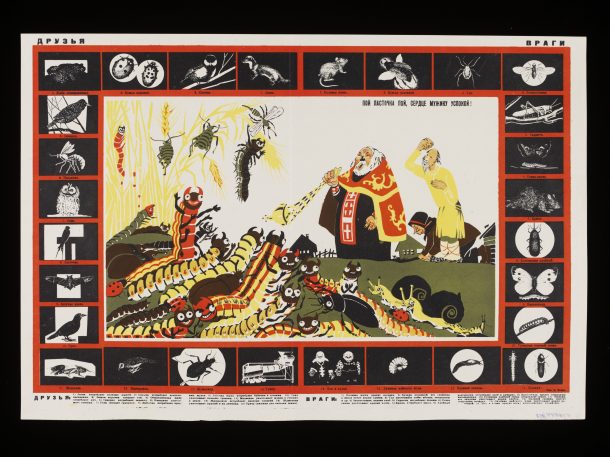

This eye-catching poster has a central image of a priest performing a religious ritual in a field. Insects mock him while attacking the crops as the peasants look on hopelessly. The text at the top of the image is from a folk song ‘Sing Swallow, Sing, Soothe the Peasant’s Heart’. The border lists friends of the peasant farmer on one side and enemies on the other. The Russian text at the bottom explains how they help or hinder the farmer, for example “The skylark kills field slugs”, and on the opposite side “The field slug spoils garden planting”.

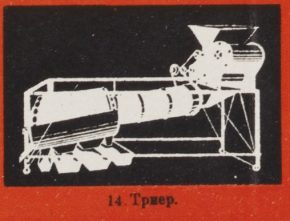

The last ‘friend’ described by the poster is a ‘trier’ – a machine for sorting and cleaning grain more efficiently than by hand. The poster was produced in the 1920s when Russia was still a predominantly rural society. The majority of the population lived off the land and agricultural progress was far behind the West .The Russian government was keen to develop agriculture and also to reach out to the vast peasant population they hoped would help create their new society.

This new society also had enemies. The last enemies listed on the poster are a priest and a kulak; they are described as ‘harmful to all peasant farmsteads’. In 1918 Russia was decreed a secular state. The new regime was hostile to religion, accusing the church of amassing riches and controlling the Russian people with false beliefs. Priests accepted payment for the many religious rituals throughout the year, including those linked to the agricultural cycle such as the crop-blessing performed by the priest in the central image. During the 1920s huge numbers of churches were closed.

A kulak was a prosperous peasant who hired others to work on their farm, or lent money or equipment to others. This label was used quite freely during the late 1920s when kulaks were singled out as harmful money-grabbing capitalists and exploiters of good soviet peasant workers. The government encouraged people to seize the farms of their ‘kulak’ neighbours. In 1929 Stalin proposed ‘the liquidisation of the kulaks as a class’, beginning a campaign of mass execution or imprisonment of ‘kulaks’ which could include anyone suspected of resisting the will of the state.

Dmitry Moor’s poster, with its brightly coloured image of comical insects, can appear amusing, but the poster’s message that demonising people by religion or class is as natural as birds eating bugs gives a chilling glimpse into life under Soviet rule.