The mummy – perhaps the iconic image of ancient Egypt. Maybe the word makes you think of an ancient body swathed in linen, or maybe, thanks to Hollywood, your first thought is Boris Karloff’s villain or Brendan Fraser’s hero. Either way, the image of the mummy is embedded in popular consciousness. However, museums today are increasingly reflecting on how best to refer to long dead, embalmed humans, and whether the word ‘mummy’ is, perhaps ironically, dehumanising. This post traces where the word came from, how it has been used, and how museums think about its suitability today.

Origins

The word mummy has a long history. It derives from Latin mumia, ultimately borrowed from Persian mumiya. This word actually originally refers to bitumen or tar, a derivation that betrays something of our historical relationship with mummies. Due to the physical appearance of ancient Egyptian bodies, and the resinous substances they often exuded, early Persian scholars noted their resemblance to bitumen, a substance widely believed to have medicinal value. When Persian works were first translated into Latin, misunderstandings deepened. The word originally referring to medicinal tar became synonymous with the Egyptian bodies themselves, and ‘mummia’ (a powder literally made from ground-up human remains, supposedly with healing properties) became a standard feature of European apothecaries from the Middle Ages until the eighteenth century.

Considered something of a wonder-cure, a booming trade in mummia developed between Egypt and Europe; Egyptian bodies were exhumed, exported and powdered in their thousands. Due to demand, and the increasingly limited supply of ancient corpses available (Egypt banned the trade of mummia in the sixteenth century), entrepreneurial but unscrupulous traders created scam powders by embalming and powdering fresh corpses, often those of criminals. Even in the nineteenth century, when mummia’s medical value had been comprehensively debunked, ground-up remains continued to be used as ‘mummy brown’ paint pigment, particularly popular amongst the Pre-Raphaelites.

The curse of the mummy?

Our modern conceptions of the mummy, however, owe much to the Victorians. Across the nineteenth century, Europe’s growing colonial influence in Egypt alongside stunning archaeological discoveries led to an explosion of popular interest in ancient Egypt. For mummies specifically, their influence was best seen in Gothic literature, where they took on multiple new personas.

Attitudes to mummies were, interestingly, somewhat gendered. In Edgar Allen Poe’s short story ‘Some Words with a Mummy’, with its reanimated Egyptian character Allamistakeo, the male mummy was a comic figure. In other instances, such as H. Rider Haggard’s ‘Smith and the Pharaohs’, female mummies were eroticised, representing forbidden desire. However, it is in literature that that the trope of the mummy as a creature of horror and fear also began to crystalise, through works like Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘Lot No. 249’ and Bram Stokers’ The Jewel of the Seven Stars. Academics also contributed to these tropes. The Egyptologist Georg Ebers wrote novels in order to popularise Egyptian lore – his book An Egyptian Princess was read across Europe and translated into multiple languages. The same comic and gothic tropes were repeated in music hall and theatre, where reanimated mummies became fixtures of the stage.

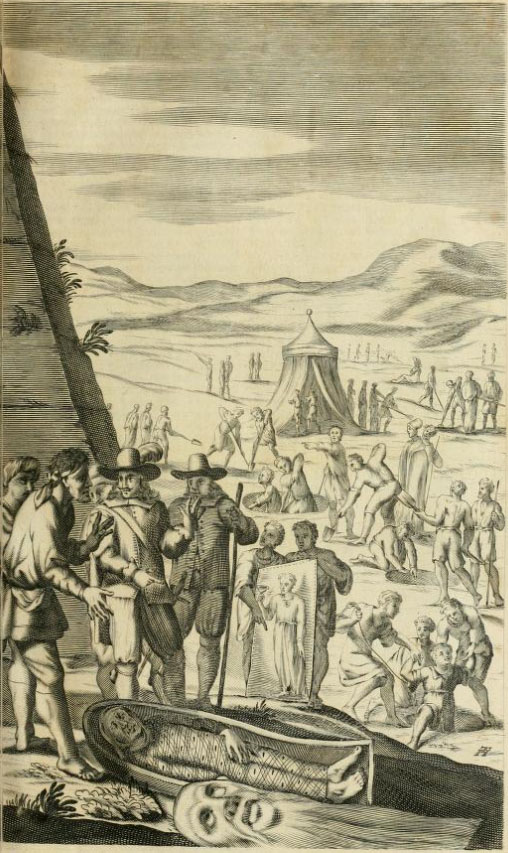

The mummy-as-spectacle was also exemplified by the unpleasant emergence of public mummy-unwrappings. Popularised by Thomas Pettigrew in Britain and George Gliddon in the United States, crowds gathered to see what mysteries lay beneath the ancient bandages. Many of the authors who went on to write mummy-themed works were themselves inspired by such grotesque displays.

An interesting conjunction of these various strands of nineteenth-century ‘Egyptomania’ is a necklace once owned by Gothic author Marie Corelli, who wrote many novels about ancient Egypt and the supernatural, and was partly responsible for popularising the idea of the ‘Mummy’s Curse’ following the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Corelli’s necklace incorporates real, restrung ancient beads; she believed it to be itself cursed by a mummy, claiming that it brought her luck but that she refused to ever wear it. These gothic tropes would of course only grow further after Tutankhamun’s discovery led to another explosion of interest in ancient Egypt, spearheaded by Hollywood.

More than a word

Today, there are increasingly conversations about whether the word mummy should continue to be used. Many argue that it is dehumanising, and some museums are now reconsidering their labelling, trialling alternatives such as ‘mummified remains’. However, others argue that ‘remains’ is also dehumanising; is ‘mummified person’ better? There are no easy answers, nor yet consensus on best practice. Some museums have amended their permanent gallery labels, and others are making changes only in temporary exhibitions. Nevertheless, it is important that these conversations happen. As well as questions around terminology, there are multiple reasons why it might be appropriate to rethink the labelling and display of individuals. The museum ethics of displaying human remains have evolved considerably, and it is vital today to display them respectfully in a way that contextualises who the person was, and to see them as more than just the processes used to preserve them. Likewise, we must consider ethically questionable ways in which many Egyptian bodies made their way to European collections.

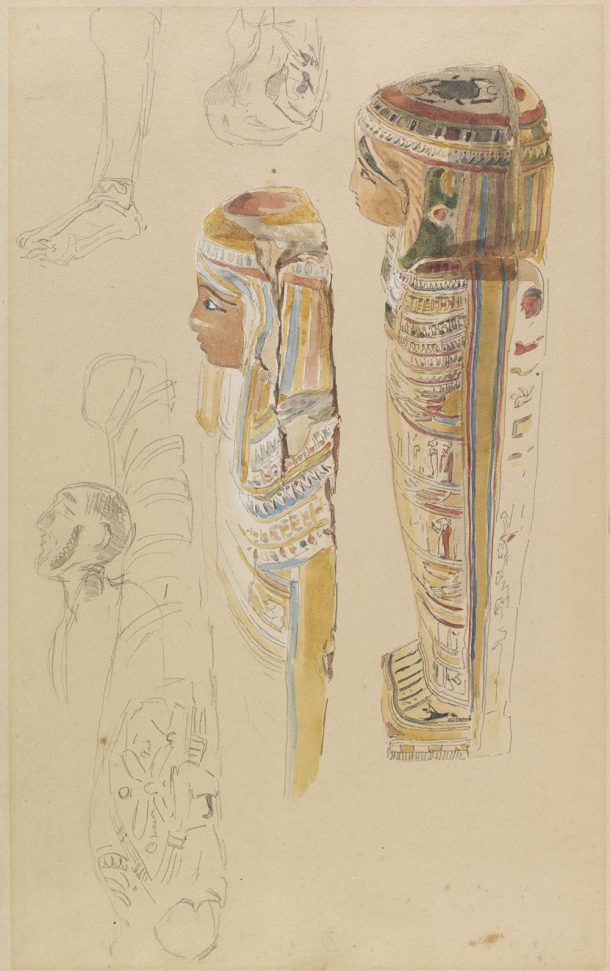

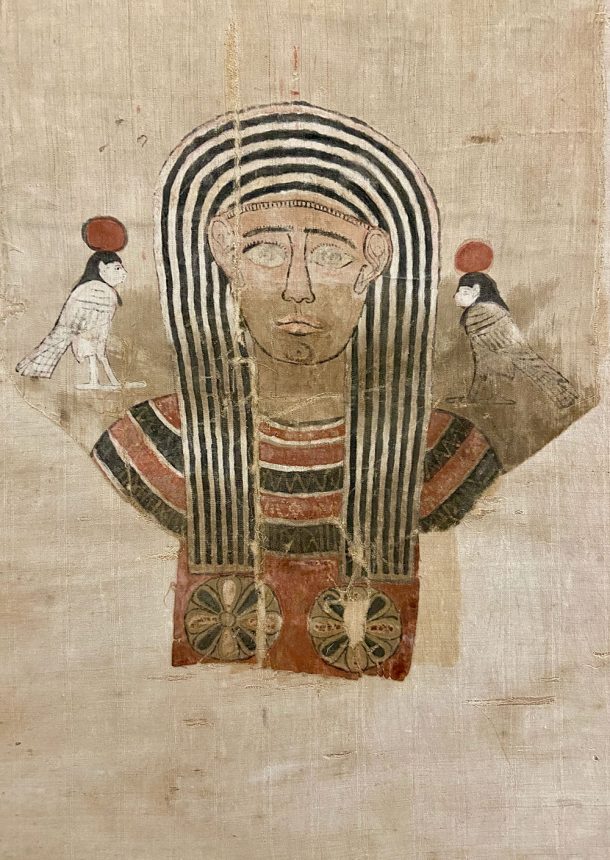

Much of this conversation relates to describing human remains, and the V&A does not have any Egyptian bodies in its collection. However, the debate is still relevant to us. We have a small number of objects related to burial and mummification, such as bandages used to wrap bodies, shrouds and fragments of coffins. These have historically been catalogued using the term mummy – ‘mummy bandages’, ‘mummy cases’ etc. In line with ongoing conversations and changes being made by other museums, the V&A is reviewing its own use of language. The museum’s Terminology Discussion Forum has compiled a list of all instances of the word in relation to our holdings, and where appropriate we will amend catalogue entries and clarify wording.

In some cases of burial equipment, such as Roman-era paintings of the deceased, the term ‘mummy portrait’ continues at present to be the accepted wording within literature and at other museums. Likewise, many of the instances of ‘mummy’ in our collection actually relate to historical photographs and drawings, where it occurs in their specific title. Changing this would be wrong, but we can add a note on the object record to explain and contextualise why the word might be seen as problematic today. In other instances relating to our archaeological collections, a valid change might be as simple as recognising that the word mummy does not necessarily need to be used. For example, there is no need to describe painted burial shrouds as ‘mummy cloths’. In any cases where terminology is amended to be more appropriate, a publicly-visible note will be kept within the catalogue of what the historic interpretation was, and why it was changed; the museum aims to improve its language where appropriate, but not hide the past.

Ultimately, the word mummy is so ingrained in popular culture—as well as academic literature—that it is unlikely ever to disappear completely. That said, museums today are making changes to reflect a more sensitive approach to human remains, and the V&A supports these. In using language to distinguish between cultural references and the sensitive study of real individuals, we retain an understanding of the past’s inhabitants as people, not displays.