21 March is Peter Brook’s 90th birthday. To celebrate we’re posting pictures from the Theatre & Performance collections documenting his life and work. Part 1 goes from his childhood until the end of the 1970s.

1. 1930s

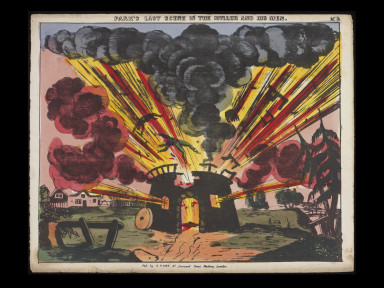

This 19th century toy theatre print is from a popular play, The Miller and His Men which finished with the spectacular explosion shown here. In his autobiography Threads of Time Brook recalls the impact seeing the show had on him as child: ‘This was my first theatrical experience, and to this day it remains not only the most vivid but also the most real [an] apocalyptic explosion, with fragments bursting from its orange core‘, S.889-2009

2. 1940s

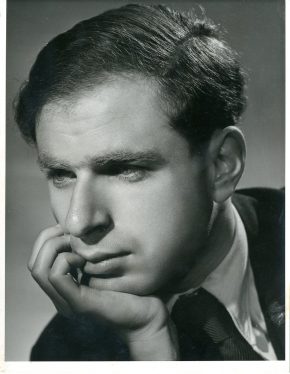

A debonair young man goes to influential photographer Angus McBean for his publicity shot.

The caption stuck on the back of the picture reads ‘Peter Brook whose remarkable production of Romeo and Juliet at this year’s Shakespeare Festival will be seen when the company opens at His Majesty’s Theatre on October 2nd [1947] for a short season.’

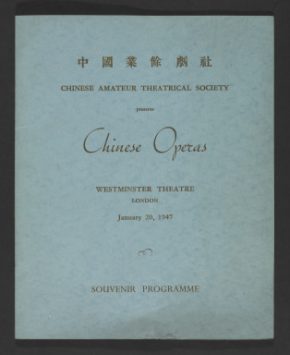

The same year, Brook first saw the acrobats in Chinese Opera who inspired his 1970 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

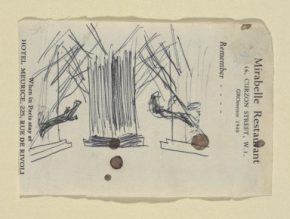

Among the papers in Brook’s collection is a scrap of paper with the following notes:

“Peking Opera: man suddenly twists and falls not only flat but crumpled into total flatness in a flash. Fights with sticks as bouncing and rebounding off centre character (women’s) stick, knocked back and at same time kicked back with foot turning twists and somer [sic, presumably somersaults]. Number for 2 with large chair, leaping and perching on arm, top-tilting chair leaning onto outstretched woman.

Monkey story – monkey juggles with flagship stick, high speed, throws sword in air, catches it in scabbard, catches one stick on top of another, lightning dives and flips.”

These memories were the starting point for Brook’s experiments with acrobatics and circus skills in A Midsummer Night’s Dream which saw actors like John Kane moving round the set on stilts and trapezes.

3. 1950s

Now an established director of theatre and opera, and moving into film, Brook worked with a number of key performers and designers during the 1950s. And socialised with them too. The picture below is from the Vivien Leigh archive and shows Brook visiting Leigh and Laurence Olivier at their country home Notley Abbey.

Brook and Olivier had worked together on the film of The Beggars’ Opera (1963). It wasn’t an easy relationship, but their next collaboration was much more successful. Brook directed a powerful version of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus starring Olivier and Leigh. As ever, he had a strong sense of how he wanted the production to look and sketched his ideas for set designer Michael Northern.

4. 1960s

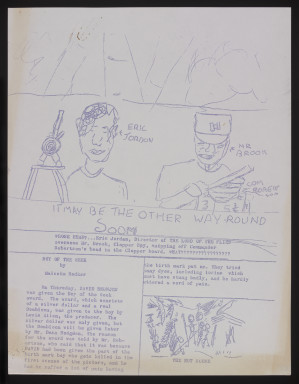

1963 saw the release of Lord of the Flies, Brook’s film interpretation of William Golding’s novel. During the filming the boys produced and distributed their own journal.

1963 saw the release of Lord of the Flies, Brook’s film interpretation of William Golding’s novel. During the filming the boys produced and distributed their own journal.

By the time the film was released Brook was back in theatre. With members of the newly formed Royal Shakespeare Company he set up an enquiry-based experimental performance project, ‘Theatre of the Cruelty’, looking at the relationship between theatre and contemporary politics. This resulted in two of his most famous productions Marat/Sade and US, which examined attitudes to the Vietnam war. US was a collaborative endeavour with actors, writers (including poet Adrian Mitchell) and director Albert Hunt.

1970s

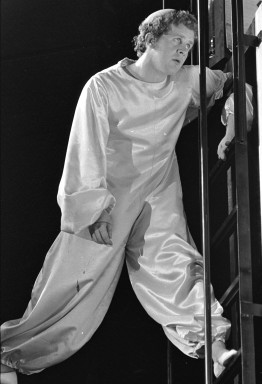

Brook’s collaboration with the Royal Shakespeare Company continued throughout the 1970s. He began the decade with an astonishing, acrobatic A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Below we see him with the company rehearsing the text after a morning of acrobatic training.

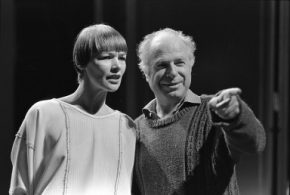

Brook left Britain to settle in France and establish his International Centre for Theatre Research soon after, but returned to direct Glenda Jackson and Alan Howard in Antony and Cleopatra.

We are grateful to the Heritage Lottery Fund for their generous support of this project.