Symmetry Breakfast is a wildly successful Instagram account that posts photos of beautifully styled breakfasts for two, plated in mirror image. Started by Michael Zee in 2013 while he was working in the Learning Department at the V&A, Symmetry Breakfast now delivers culinary inspiration to hundreds of thousands of followers around the globe. It’s found a niche by celebrating the most unsung meal of the day and re-inventing breakfast as an opportunity for injecting beauty and joy into daily routine.

The project has grown into a full time occupation for Zee, but Symmetry Breakfast has returned to the V&A as part of the exhibition Food: Bigger than the Plate, where it demonstrates how people are using social media to develop their creative talents with food. I caught up with the man behind the breakfasts (many initially assumed it was a woman) to find out more about how the account has been shaped by his twin passions for food and design.

What inspired you to start getting creative with breakfast?

My partner Mark was working in the Burberry design team which often meant working late under tight deadlines, so I wouldn’t see him in the evenings. Breakfast was the only time we had together. So I made the decision to start putting a bit of effort into preparing him something before he went to work. It was about thinking: how can I make breakfast nicer? Can I make my own version of that shop-bought bread? Or, that’s a nice plate. And suddenly you start accumulating things, not just physical things, but knowledge, recipes that you know work. I was always a good cook, but never had a focus to try things out so consistently. It really changed the way I cooked. I am in the kitchen every single day now.

How did making breakfast for your partner every morning (and, yes Mark, we’re jealous) develop into a viral Instagram account?

It started as a pet project. Five years ago Instagram was a new platform and we didn’t have influencers and digital marketing strategies. It was just about people having fun posting images, so there was no strategy involved. I just noticed that the breakfasts I made for Mark and myself made an attractive mirror image and started posting pictures of them. Initially it was only personal friends who were seeing them. Then Mark’s old boss said he really liked my breakfast posts and suggested putting them on a separate page. I hadn’t thought about having a more cleanly curated portfolio of images. They were just in amongst a mishmash of pictures on my own personal Instagram account. So then it became a thing and I had to work out what it was going to be called – symmetrical breakfast was too long, so symmetry breakfast was born.

In many ways Symmetry Breakfast is as much a design project as it is a culinary one. How can design contribute to a great breakfast?

I’m interested in how design choices can make our lives better. It’s about beauty and comfort and pleasure. A well-designed piece of clothing makes you feel good. It’s the same with food. If you’ve prepared a beautiful piece of food for someone you love, you want to choose a plate that contributes best to the overall experience. Those choices can make a huge difference. Obviously Instagram is a visual medium, but the visual is also an important part of the multi-sensory pleasure of actually eating.

You have a great eye for objects and you use tableware in styling Symmetry Breakfast to help create the geometry and set off the colours and textures of the food. Does the tableware ever inspire the cooking?

Ceramicist Billy Lloyd makes beautiful ‘Oxbow’ plates. They are three segments of a circular plate that come apart and can be reconfigured to wind around the table like an oxbow lake. I’ve used them on Symmetry Breakfast to create multi-course breakfasts. Dinner usually has multiple courses, but breakfast has traditionally been a functional one dish/one bowl meal to get people started for the fields and factory. Where routines have changed, so can breakfast. That’s why brunch has evolved.

When you started Symmetry Breakfast you were immersed in design through your day job at the V&A. Obviously we’re keen to claim you as a home-grown talent! Did your museum career inform the project?

Absolutely! Part of my job was working with students and teachers to find objects in the collections that matched their area of interest or study. Time and again I found myself suggesting objects that were all over the museum, different materials, processes, periods and styles, often things they weren’t expecting to see. With Symmetry Breakfast, my feed and interests jump around in quite an erratic way, how one ingredient can be used across multiple recipes and cultures over the course of a week of cooking is not only exciting to me but also practical in the kitchen.

Food is one of the best ways to connect people with many of the objects I love at the V&A and gives context to functional design. A Chinese wine cup might look nothing like a contemporary wine glass, but when you taste baijiu, an incredibly strong spirit popular in China, you can understand why a small cup will suffice!

I have to ask – do you have a favourite V&A object?

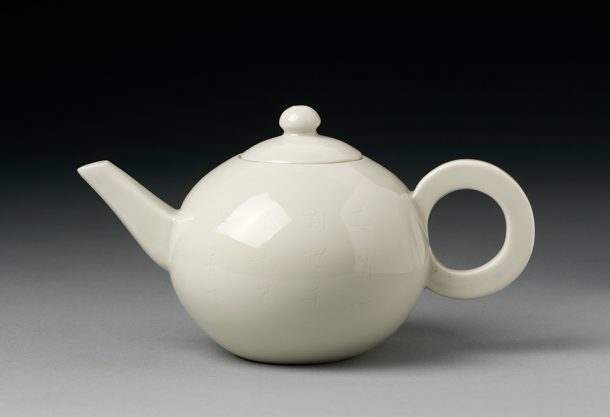

My personal favourite object is a teapot on display in the ceramics gallery. The body of the teapot is almost completely spherical and it has a beautiful, translucent mother of pearl glaze. It has an aesthetic we associate with early 20th century modernism, but it was made in China around 1690. We have such clear timelines in design history about how styles evolved, but there are so many objects that appear to contradict that and tell more complex stories about human creativity. I love showing the teapot to people because they are always shocked when they find out it is from the 17th century. I went to Jingdezhen last year, which has been a centre for porcelain production for centuries and asked a maker there whether he could reproduce the teapot. The answer was no – impossible. The technical knowledge needed to make it is no longer current.

As people in the West have become more familiar with international cuisines, breakfast seems to have been the meal most resistant to change. How is social media shifting our tastes?

I think that naturally we are quite stubborn, we’d rather have what we find comforting and familiar at 7am than something that would excite us too much. Save that for when you’ve woken up a bit and you’re not in your pyjamas! But without having to travel, social media has allowed us to see normal life as it happens almost anywhere in the world. Someone in Sarawak, Malaysia tucking into a breakfast of laksa can quickly put our white sliced toast into perspective. From a western lens, we are finally starting to see that the world is not just about us, but that we are interconnected.

The danger of social media is that we can quickly lose track of where things come from – an image is shared a thousand times and so quickly we have no trace of its origin. Likewise the idea of cultural ownership, and how that is appropriated, how ‘authentic’ a cuisine is and even how nationalism can play a role in food is slowing down its natural evolution. We defend the boundaries of our cuisines like borders, even if it limits us. I’m fascinated that Italians and the Irish and almost all of Asia talk about authenticity, yet potatoes, chillies and tomatoes are all recent introductions from the Americas.

What have you learned by exploring the world through breakfast?

There is a lot of commonality, even when cultures haven’t directly crossed paths – every culture has some sort of pancake, some sort of dumpling, some sort of porridgey, ricey, milky stew. We have similar cooking implements that use the least fuel possible, like a wok, a comal or a tandoor oven that can maximise heat. Everyone came up with the same idea for cups and bowls and plates and sharing. Necessity has created designs that are intuitive. They are all hurdles that we have overcome. We’ve all come to the same conclusion.

There is a long history of food being used in visual culture from painting to the early days of photography, to film. How do you think the current phenomenon of ‘food porn’ photography on social media fits into that story?

Food has been used either to portray purity or sexuality or lust. It has always been there throughout art history as a device to comment on moral worth, but I think social media is moving away from those kinds of signifiers. If you look at a burger on Instagram that is stacked 12 patties high, it is simply a glorification of food. It’s about pure gluttonous excess. I also think what people are overwhelmed by is not the content itself, but the volume of content that is being produced. Today, there are more photographs made in a day that in the entire period from 1900 – 2000.

That said, food is still being used symbolically to communicate, whether it’s Obama drinking a pint or Trump eating a McDonalds. I recently discovered a small bakery in a backstreet in Hong Kong making mooncakes with slogans supporting pro-democracy protests. In Cantonese history, mooncakes often carried slightly vulgar or subversive messages – that was the pleasure in baking them. This bakery took a traditional cultural form, updated it in the context of the current demonstrations in Hong Kong and reached a global audience through social media.