Walking through the Islamic Middle East gallery (Room 42, The Jameel Gallery) at the V&A South Kensington is like opening a window on the culture and practice of collecting Islamic art in the Victorian period. Much of what we see on display today was acquired by a group of art enthusiasts in the nineteenth century, which included some of the most famous names associated with the V&A, such as William Morris, Lord Frederic Leighton and George Salting. While sometimes more associated with the art and design of various other traditions, they were united by a dilettante interest in the material culture of the Middle East and what they would have referred to as Persia. Some of the items in the gallery are linked by an event key to the history of Islamic art in Europe: the Persian and Arab Art exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1885.

The Burlington Fine Arts Club (BFAC) was a gentleman’s club founded in 1866 by a group of enthusiasts whose main objective was the promotion of artistic knowledge and the sharing of passion for the arts. The club was near Burlington House, and it served as a hub for its members to discuss art history and showcase their private collections in themed exhibitions, which were organised yearly or every 6 months; the club also hosted a library full of periodicals and books on various artistic subjects and published catalogues of its yearly exhibitions.[1] The BFAC had strong links with the institution that would become the V&A; indeed one of the museum’s early curators, John Charles Robinson (1824 – 1913), was one of the club’s founders.[2]

The first exhibition at the BFAC was held just one year after its founding, in 1867, and was centred on Rembrandt’s etching; less than two years later, in 1869, the theme was ‘Oriental porcelain’ after which non-European and decorative objects became important subjects for the club.[3]

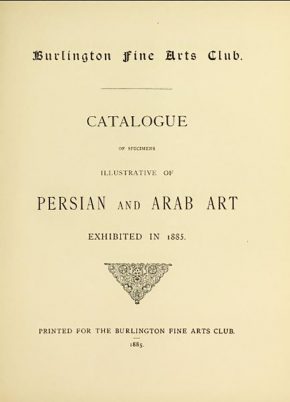

In 1884 Charles Drury Fortnum (1820 – 99), an advisor to the South Kensington Museum and a collector of maiolica, proposed to host an exhibition on ‘Damascus Rhodian Persian and other kindred wares’; the theme was broadened significantly and in 1885 the exhibition of Persian and Arab Art was unveiled to the public, including not only ceramics, but also textiles, carpets and metalwork.

Many of the pieces lent to that exhibition found their final home in the South Kensington Museum (what is now the V&A), and are on view in the Islamic Middle East Gallery. Their presence in the exhibition and subsequent history helps us to understand the Victorian ecosystem of collecting.

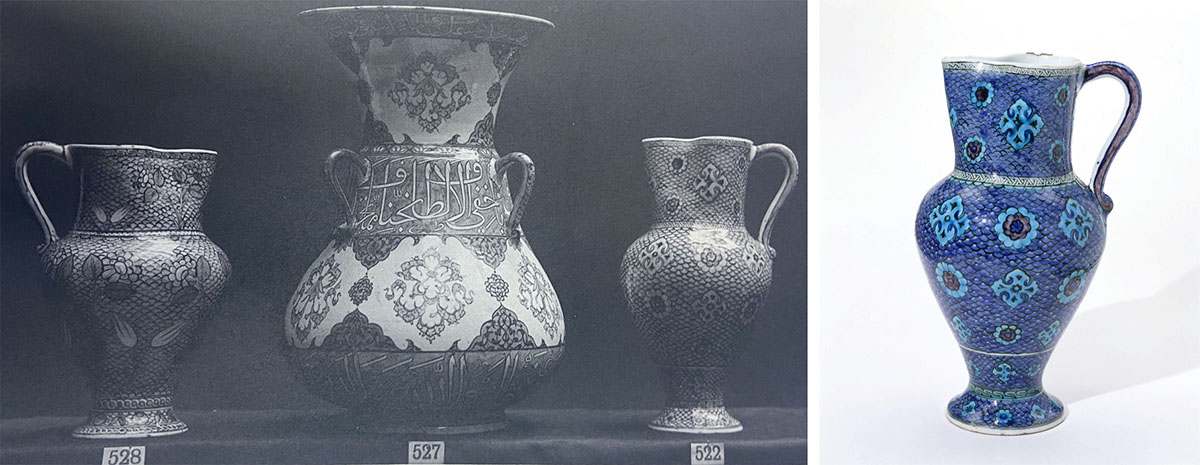

The exhibition opened on 18 March 1885 and was accompanied by a catalogue that listed all the 606 works exhibited; it featured an introduction by Henry Wallis (1830 – 1916), a pre-Raphaelite painter interested in Islamic art and passionate about ceramics, and contained 32 plates with black and white photographs of some of the works on view.[4] The list of contributors included William Morris (1834 – 96), Sir Frederic Leighton (1830 – 96), George Salting (1835 – 1909) and Charles Drury Edward Fortnum (1820 – 99). They were all Art Referees, meaning that they held a special status as official advisors to the South Kensington Museum. They were joined by Leighton’s architect George Aitchison (1825 – 1910), and the collector Louis Huth (1821 – 1905).[5]

William Morris was closely connected with the museum, advising its board on purchases, and also often supporting some of them with financial contributions.[6] Best known for being the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement, Morris was also very interested in the burgeoning Islamic art market and – although not a member of the BFAC at the time – he lent 12 items to the exhibition, most notably the enormous vase carpet, which was later purchased by the V&A and now is hanging on the west wall of the gallery (Museum no. 719-1897). Morris was partly responsible for the acquisition of the vast Ardabil carpet, also found in the gallery, as he, alongside others, persuaded the Museum to raise the then-enormous sum of £1750 to purchase it in March 1893.

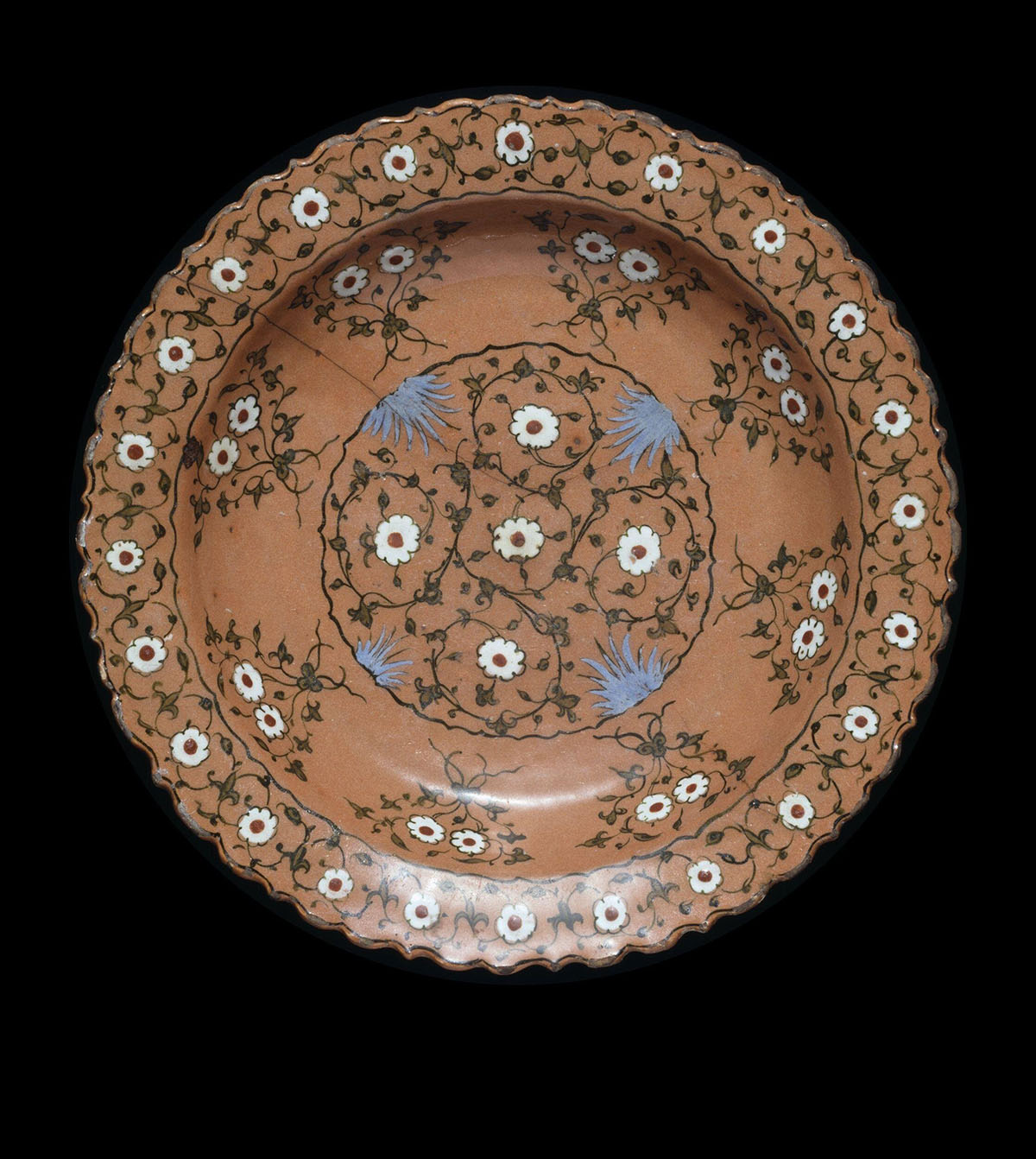

Morris was close friends with Sir Frederic Leighton, whom he advised on the construction of the Arab Hall at the latter’s home in Holland Park – it was completed in 1881. Sir Frederic himself contributed extensively to the 1885 exhibition, lending 46 items, mainly Persian and Ottoman ceramics. After his death, the collection was dispersed at auction, selling over three days by Christie, Manson & Woods between 8 and 10 July 1896. Some of those possessions eventually found their way to the V&A too; according to the museum’s inventory two of Sir Frederic’s pieces were acquired from a Major Myers, at 54 Piccadilly, for £23: a turquoise Safavid flask with molded floral decoration (Museum no. 711-1896) and a jug with dark blue glaze (Museum no. 712-1896).[7]

Two other members of the BFAC were key contributors to the exhibition, Louis Huth and George Salting, and some of the pieces lent and illustrated in the catalogue are now part of the V&A collection and are on view in the gallery.

Louis Huth was an eclectic collector, member of the BFAC and a patron of various artists. His circle of friends included George Frederic Watts, who painted Huth’s wife, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with whom he shared a passion for Chinese ceramics.[8]

Huth lent 27 items to the 1885 exhibition, mainly Ottoman ceramics. When he died in 1905, his collection was dispersed at auction. Unlike now, the names of buyers were public and often recorded – and thanks to these records we can trace the ownership of various pieces and gain a better appreciation of the commercial practices and habits of the collectors. Some of Huth’s pieces were purchased directly by his close friend George Salting, an avid collector and member of the BFAC who would become a key figure in the history of the V&A.[9]

Many of the pieces on view in the gallery are associated with George Salting and were part of his collection, donated to the nation upon his death. Born in Australia to parents of Danish origin, Salting attended Eton and later read classics in Sydney. After the death of his father in 1865, he and his brother inherited a considerable fortune, £30,000 pounds a year. This generous allowance enabled him to build an impressive art collection encompassing everything from ceramics to prints to paintings.

The northern wall of the gallery displays a collection of Iznik, bequeathed by George Salting in 1909; within this group, five items were originally owned by Huth and were illustrated in the BFAC catalogue.[10]

In fact it is really thanks to George Salting that so many of the pieces exhibited at the BFAC show ended up in the V&A collection. Salting was buying at auction and from dealers, and by 1885 had already assembled an impressive collection of Persian and Middle Eastern ceramics. He lent 29 items to the exhibition, 9 of which are now on display in Islamic Middle East gallery, including a Safavid carpet of Polonaise design. At the time of his death, he left his entire estate to the nation, with his collection of paintings going to the National Gallery, his prints to the British Museum, and all the objects to the V&A. The quality of the ceramics now in the gallery is thanks in significant part to George Salting.

By the time it closed the exhibition had drawn 4,198 visitors; an extraordinary number in comparison to most of the other exhibitions held at the BFAC. To put that in some context, by 1885 only two others had attracted more guests: Painting, drawings and engravings by William Blake (1876 – 6,143 visitors) and Pictures and drawings by the late D.G. Rossetti (1883 – 12,133 visitors).[11]

In less than a quarter of a century the Persian and Arab Art exhibition was to become a key point of reference for the art market, adding greatly to the provenance of any item that could be shown to have been exhibited. In 1901, when the effects of the late Charles Isaac Elton (who lent 48 items to the exhibition) were sold at auction, the title page of the sale catalogue announced that ‘many pieces of which were exhibited at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in the Exhibition of Persian and Arab Art, 1885’.[12]

Further reading

Gadoin 2012

Isabelle Gadoin, “George Salting (1835 – 1909) and the discovery of Islamic ceramics in 19th-century England”, Miranda [Online], 7 | 2012; (accessed 28 July 2023)

Gadoin 2022

Isabelle Gadoin, Private Collectors of Islamic Art in Late Nineteenth-Century London: The Persian Ideal, London 2022

Pierson 2017

Stacey Pierson, Private Collecting, Exhibitions, and the Shaping of Art History in London: The Burlington Fine Arts Club, New York 2017

Williamson 1919

George Williamson, Murray Marks and His Friends, London 1919

Notes

[1] Exhibition catalogues have been published since 1868 but not all of them were illustrated. Between 1868 and 1898 only 9 catalogues were illustrated – the Exhibition of Persian and Arab Art being one of them, Gadoin 2023, p.81.

[2] The history of the club and its exhibitions has been published by Dr. Stacey Pierson, Private Collecting, Exhibitions and the Shaping of Art History in London. The Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, 2017.

[3] Before the Persian and Arab Art exhibition of 1885, the BFAC held an exhibition on Japanese Lacquer in 1875 – 76 and another one on Chinese and Japanese Art in 1878 – 79. Pierson 2017, pp.164–8.

[4] The photographic negatives used to make the 19th-century images were not panchromatic, and they were often overly sensitive to blue light; for this reason, in the plates of the catalogue, the blues are often transfixed as lighter colours and look like whites.

[5] The List of Contributors in the catalogue records 41 lenders, of which 21 were members; in the plate section two additional lenders are mentioned in connection to pieces not listed in the catalogue: the South Kensington Museum, which lent a collection of fragments illustrated in plate 2, and Mr. A Seymour.

[6] Along with supporting the acquisition of the Ardabil Carpet (Museum no. 272-1893), William Morris also donated £20 towards its purchase for example.

[7] Another piece lent by Sir Frederic in the exhibition, entry 540, is now in the Bruschettini Collection, Genoa.

[8] George Frederic Watts RA (1817 – 1904) painted several portraits of Mrs Helen Rose Huth, the most famous is dated 1858 and is now in the Dublin City Gallery; another was sold at Christie’s London, 5 June 2008, lot 49. Rossetti and Huth used to buy Chinese ceramics from the same dealer, Murray Marks. Williamson 1919, p.34.

[9] The property of Louis Huth was sold by Christie, Manson & Woods in two sales spread between five days, between 17 and 23 May 1905.

[10] The other Iznik pieces are C.1982-1910, illustrated in plate 11c; C.1985-1910 in plate 12; C.1989-1910 in plate 13 and C.1981-1910 in plate 11c.

[11] The total number excludes the members of the club, who were not counted. Pierson 2017, pp.101 – 10 and pp.164 – 65.

[12] Christie, Manson & Woods, 26 March 1901.