Oh dear to us ever the scenes of our childhood

The green spots we played in the school where we met

The heavy old desk where we thought of the wild-wood

Where we pored o’er the sums which the master had set

I loved the old church-school, both inside and outside

I loved the dear Ash trees and sycamore too

The graves where the Buttercups burning gold out vied

And the spire where pelitory dangled and grew

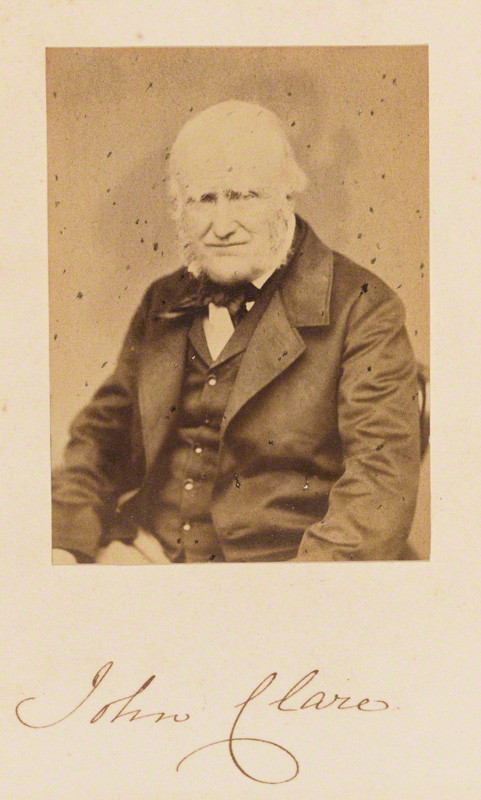

These are the first lines of Childhood, written in 1840, an evocative poem by John Clare (1793 – 1864). The poems of Clare have the love of his birthplace of Helpston, Northamptonshire, woven within them and he is rightly known as a great poet of the English countryside. He lived in a period of radical change in the countryside and his poems feature powerful memories of childhood and act as a reminder of how childhood differs but is also similar through the social classes and the centuries.

On a recent trip to John Clare’s cottage in Helpston I encountered the poetry of Clare for the first time. Clare was born in 1793 and lived a rural childhood. His formal education ended when he was 11 but he was a voracious reader and enjoyed the education he did receive. Clare was in the main self-educated. His mother Ann was illiterate and his father Parker was a thresher, who brought to John folk songs and ballads which influenced John’s writing. His parents would assist and help John at every opportunity in regards to his learning. [1]

One of his surviving school exercise books proves by the inscription on its cover how seriously Clare took his schooling,

‘Steal not this book for fear of Shame

For here doth Stand the owners Name.

John Clare’ [2]

The cottage of Helpston was his home as a child and would go on to be the home of his family also. The comfort he felt as a child in his cottage can be perceived in To My Cottage;

Thou lowly cot where first my breath I drew

Past joys endear thee childhoods past delight

Where each young summer pictures on my view

And dearer still the happy winter night

When the storm pelted down wi all his might

And roard and bellowed in the chimney top

And pattered vehement gainst the window light

And oer the threshold from the eaves did drop

How blest Ive listened on my corner stool

Heard the storm rage and huge my happy spot

While the fond parent wound her wiring spool

And spard a sigh for the poor wanderers lot

In thee sweet hut I all these joys did prove

And these endear thee wi eternal love[3]

Throughout his life Clare would look back on his childhood with fondness, his writing is full of the dialect and slang of his times. We again return to Childhood;

…To be in time for the school or before the bell rung.

There’s the odd martins nest o’er the shoemakers door

On the shoemakers chimney the Old swallows sung

That had built and sung there in the season before

Then we went to seek pooty’s among the old furze

On the heath’s, in the meadows beside the deep lake

And return’d with torn clothes all covered wi’ burrs

And oh what a row my fond mother would make

This poem goes on to capture the imagination of children at play;

Then to play boiling kettles just by the yard door

Seeking out for short sticks and a bundle of straw

Bits of pots stand for teacups after sweeping the floor

And the children are placed upon school-mistress’s awe

There’s one set for pussy another for doll

And for butter and bread they’ll each nibble an awe

And on a great stone as a table they loll

The finest small teaparty ever you saw

His autobiographical writing testifies to his thirst for knowledge as a child;

‘ I at length got an higher notion of learning by going to school and every leisure minute was employ’d in drawing squares and triangles upon the dusty walls of the barn . . . this was also my practise in learning to write . . . I also devoured for these purposes every morsel of brown or blue paper (it mattered not which) that my mother had her tea and sugar lapt in from the shop but this was in cases of poverty when I could not muster three farthings for a sheet of writing paper . . . the saying of ‘a little learning is a dangerous thing’ is not far from the fact . . . after I left school for good, (nearly as wise as I went save reading and writing), I felt an itching after every thing . . . I now began to provide my self with books of many puzzling systems Bonnycastles Mensuration, Fennings Arithmetic and Algebra was now my constant teachers and as I read the rules of each Problem with great care I preserved so far as to solve many of the questions in these books . . . my pride fancied it self climbing the ladder of learning very rapidly on the top of which harvests of unbound wonders was conceived to be bursting upon me and was sufficient fire to prompt my ambition …’[4]

It was not however just academic books he read;

‘About now all my stock of learning was gleaned from the Sixpenny Romances of ‘Cinderella’, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, ‘Jack and the beanstalk, ‘Zig Zag’, ‘Prince Cherry’, etc., and great was the pleasure, pain or surprise increased by allowing them authenticity for I firmly believed every page I read and considered I possessed in these the chief learning and literature of the country. But as it i common in villages to pass judgement on a lover of books as a sure indication of laziness I was drove to the narrow necessity of stinted opportunities to hide in woods and singles of thrones in the fields on Sundays to read these things which every sixpence, through the indefatigable savings of a penny and halfpenny, when collected was willingly thrown away for them as opportunity offered when hawkers offered them for sale at the door …’[5]

Fame would come to John Clare in 1820 when his book Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery (1820) was published by the same publisher of Keats. Clare would have three other books published in his lifetime full of songs, sonnets and poems, The Village Minstrel (1821), The Shepherd’s Calendar (1827) and The Rural Muse (1835). These however would not prove as popular as his first.

Two years after the publication of The Rural Muse, Clare suffered a loss of memory and delusions and voluntarily entered High Beech Asylum in Epping Forest. This was perhaps brought on by his taste of the high life in London at the height of his fame and his subsequent falling out of favour with the literary establishment.

In 1841 Clare left the High Beech Asylum and walked home to Northborough, some 80 miles which took him four days. He states in his account of this walk, Journey out of Essex, that he survived by eating grass by the roadside. He is convinced during this journey that he will meet his first love Mary Joyce and he was married to her. By this time John was married to Patty Turner and had seven children with her. His relationship with Mary had ended in 1816 and she had died in 1838.

John Clare’s mental health would not improve and he was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum on 29 December 1841. The certificate for application to the asylum stated his occupation as gardening and in the section asking whether insanity was preceded by any severe or long continued mental emotion the answer given was ‘after years addicted to Poetical prosings.’

John Clare would spend the reminder of his life in the Asylum, some 23 years and continue to write. He struggled with his memory throughout his time as in this poignant reply to a letter he received in 1860,

‘Dear Sir,

I am in a Mad house and quite forget your Name or who you are you must excuse me for I have nothing to communicate or tell of and why I am shut up I don’t know I have nothing to say so I conclude

yours respectfully

John Clare‘[6]

Perhaps Clare’s thoughts on childhood were mixed with a wish to return to a simpler time, a time when he could read and write with no pressure from anyone regarding expectations.

I Am is perhaps his most well known poem, written while in Epping Forest and Northampton Asylum –

I am – yet what I am, none cares or knows;

My friends forsake me like a memory’s lost: –

I am the self-consumer of my woes; –

They rise and vanish in oblivion’s host,

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes:-

And yet I am, and live – like vapours tostInto the nothingness of scorn and noise, –

Into the living sea of waking dreams,

Where there is neither sense of life or joys,

But the vast shipwreck of my lives esteem;

Even the dearest, that I love the best

Are strange – nay, rather stranger than the rest.I long for scenes, where man hath never trod

A place where woman never smiled or wept

There to abide with my Creator, God;

And sleep as I in childhood, sweetly swept,

Untroubling, and untroubled where I lie,

The grass below – above the vaulted sky.

In 1989 John Clare rightly took his place amongst the great poets in Westminster Abbey when a plaque to him was unveiled by Poet Laureate Ted Hughes.

Clare is still relatively neglected in terms of knowledge of poetry but deserves to be more well known, his writing captures the life of the rural poor and the sheer joy of childhood.

Every year on the date of John Clare’s birthday, school children from John Clare Primary School in Helpston parade through the village and place their midsummer cushions of flowers around Clare’s grave. Two mottos are written around his grave, “To the memory of John Clare, Northamptonshire Peasant Poet’ and ‘A Poet is Born Not Made’.

with thanks to Dr Valerie Pedlar, Chairman John Clare Society and Katy Canales, Assistant Curator (ACDP), V & A Museum of Childhood.

For further information on John Clare’s Cottage please see

[1] For a detailed biography of Clare see E. Robinson and D. Powell (eds.), The Oxford Authors: John Clare, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984) and E. Robinson and D. Powell( eds.), John Clare by Himself, (Manchester, Carcanet Press, 2002)

[2] Clare Cottage guide book, (John Clare Trust, Peterborough, n.d.), p. 4

[3] Written in the period c. 1812 -1831 also known as the Helpstone period.

[4] The Oxford Authors: John Clare, pp. 430 -431

[5] The Oxford Authors: John Clare, p. 429

[6] Letter to James Hipkins, transcribed in E. Robinson and D. Powell( eds.), John Clare by Himself, (Manchester, Carcanet Press, 2002), p. 283.