The T-shirt is one of the world’s most ubiquitous garments, produced for both the high street and haute couture. It is 101 years since it was officially recognised as outerwear, and on the 2nd September the V&A opened a small display in its fashion galleries, drawing from the extensive collection of T-shirts in the Textiles and Fashion and Theatre and Performance collections. The display reflects the role the T-shirt has played in subculture, street culture, politics and art and in this blog post, the first in a short series, I will be expanding on the development of tee from underwear to outerwear.

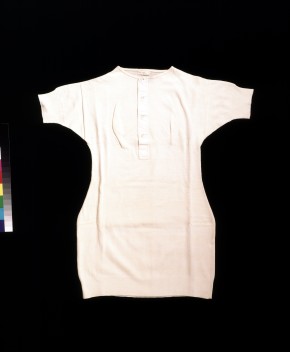

Before the mid 19th century, a man’s underwear would consist of a white shirt with long shirt tails that were tucked between the legs. In the 1840s, the woolen undervest was introduced in Britain for both men and women, was generally made of calico and became popular with labouring men as it was sweat absorbing and easy to clean. The rise of the Victorian Dress Reform movement, a campaign calling for rational dress to replace restrictive clothing such as the corset, led to the undervest gaining in popularity. The vest shown here was displayed at the Great Exhibition in 1851, as an example of technology in knitting and advances in shaping to fit, specifically the female figure.

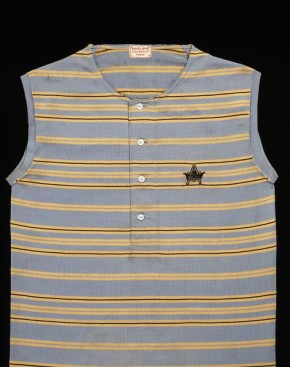

In America, innovative underwear took the form of the knitted union suit, a one-piece underwear of flannel, with long arms and legs, which buttoned up the front and had a flap in the rear allowing the wearer to go to the toilet without removing the entire garment. It became popular with men as well as women, and was patented in 1868. As this garment’s popularity waned it was increasingly replaced by two-piece underwear, although it was still worn by some working men. Two piece underwear in Britain was known as combinations, and the striped Doucet Jeune vest from 1890, shown below and as part of the display, is the top half of a set. It is from these garments that the t-shirt as we know it developed.

The transformation of the t-shirt from underwear to outerwear has been attributed to the Navy, both in Britain and in the US. In the late 19th century, the British Navy wore a sleeveless heavy woolen undershirt under their uniforms. When working on deck they were allowed to wear just this undershirt. Likewise, around the early 1880s, the uniform of the US Navy consisted of a v-necked pullover jersey with, visible underneath at the neck, a white button up flannelette undershirt with square neck. Again, once the ship was out at sea, it was often worn by itself, while the sailors required more flexible and comfortable clothing to perform the laborious tasks needed to run the ship. Although this kind of flannelette underwear had been around for many years, this was the beginnings of its use as outerwear. It was officially added to the US Naval uniform in 1913, with the introduction to the naval uniform regulations of a white buttonless woolen “crew” neck undershirt with short sleeves, with a vaguely T shaped silhouette, which could be worn on its own when at sea. Later, during the First World War, U.S. soldiers noticed the lighter cotton long-sleeved undershirts worn by French soldiers, which were cooler in the summer and dried more quickly in the winter. They brought them home and the cotton T-shirt as we know it was developed. This picture of a crew at sea from 1914 features a sailor in crew shirt in the front row.

In my next post, coming next month, I will look into how the development of the slogan tee cemented the t-shirt’s place in our wardrobes. In the meantime, T-Shirts 101 can be seen at the V&A in the Fashion Galleries until March 2015.

Hello,

I was just wondering when the next blog post in the ‘T-shirt 101’ series will be posted? This was such an interesting read and I am eager to learn more.

Thank you

Emma Kinsella

Dear Emma,

Thank you for your kind comments. The next post is coming very shortly, please check back next week!

Kristian