The new normal of Covid-19 has had profound consequences, on our bodies, psyches, relationships, and most visibly on the ways in which we dress (or don’t) every day. During the early months of British lockdown, the world seemed to be divided into roughly two groups: people who decided to only wear comfortable loungewear, and people who continued to dress up in the morning with pre-pandemic clothes as if nothing had changed.

There has been much talk about the rise of loungewear, sweatpants and pajamas during the pandemic, but not everybody surrendered to the new trend. Some people found dressing up in the morning a way to maintain a connection to the old routine. Of course, there are many different nuances in between the two polar ends of the spectrum. A recent interview series featured in Rarely Wears Lipstick strove to capture changes in the way of dressing during lockdown and isolation and to “reveal some of the many and varied personal stories relating to fashion and dress in 2020.”

Aside from the personal stories, many months of lockdown produced new global fashion trends. We have witnessed the rise of ‘waist-up dressing’ and how brands have cleverly capitalised on new working patterns and moved logos in the now more visible zoom neck area. Make-up brands have seen a sharp decline in the sale of lipsticks, which became difficult to use while also wearing face coverings. On the contrary, the increase sales of mascara and eye shadow highlights how the eyes have taken centre stage.

While observing these trends, I was pondering the pandemic fate of one particular accessory: the bag. I have spent the last two and half years thinking and researching bags from different cultures around the world while curating the exhibition, Bags: Inside Out. While news from the early stages of Covid-19 pandemic were emerging from China and Italy in February 2020, here in London we were preparing to install the exhibition which was due to open on 25 April 2020. When the British prime minister announced a national lockdown on 16 March 2020 all the objects were already selected, conserved and mounted waiting in our stores to be displayed in the exhibition space. As a result of the announcement, the V&A, alongside all other British museums, had to close their doors and the Bags exhibition had to be postponed to a date to be confirmed.

As weeks passed, I stopped working at the museum while furloughed and forgot all about bags, while being a full-time mom. This did not last long, as everywhere in the press I started reading reports and warnings on the imminent death of the handbag. As many of us did not commute to work, did not travel and no longer socialised in the evening, the handbag was deemed obsolete.

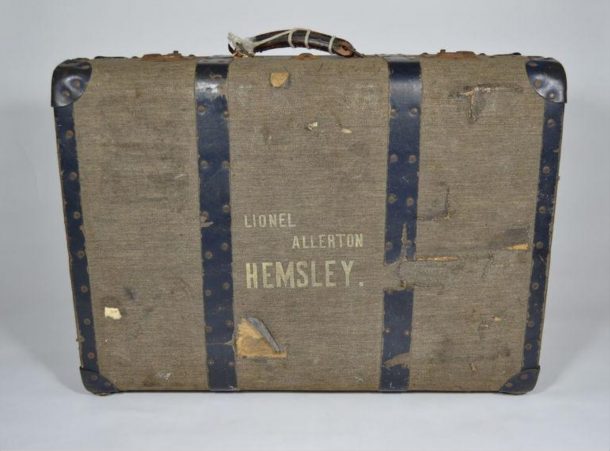

Fashion articles focused on bags had a double tone: at first nostalgic of the bygone times when we could use our precious bags on multiple occasions throughout our busy day, but at the same time critical of past trends, such as mini bags or the oversized runway trend of 2020. Was the bag gone forever, or, as one journalist suggested, only useful as a storing container for our home? Would the bag as we knew it, end up as many historical trunks have – first used as luggage and now as pieces of furniture?

In April, while many of us resorted to use pockets, trusty cycle backpacks and cross body bags that left our hands free when moving locally during lockdown, something unexpected happened. China started to lift its restrictions and news arrived reporting that the Hermès store in Guangdong recoded 2.7 million US dollar sales on the day of reopening.

In the months that followed, while we witnessed retail and high street shopping suffering, we also saw vintage websites and online auction houses increase their sales of bags. With more time available to spend online and the bag’s mantra of ‘one size fits all’, it was easier to buy handbags rather than other items of clothing online as no fittings were required. Christies even sold its most expensive handbag ever in an auction in November 2020 in Hong Kong. Some luxury brands raised their prices twice on many handbag lines during 2020 to recuperate the loss of income on other lines during the pandemic. Although the luxury sector had suffered during the pandemic, certain bags have become even more desirable.

Experts highlighted how some consumers who retained their jobs during the pandemic had more disposable income. As a consequence of savings made on not travelling, many decided to gift themselves bags and accessories as special treats. Some considered these luxury goods as a safe investment in an uncertain financial market. Interestingly, the bags that have enjoyed more of a resurgence have been classic styles, also deemed status symbols, such as handbags by Hermès, Dior and Chanel.

But why are people still buying bags if they cannot be used?

Bags are certainly functional objects, but, as we explore in Bags: Inside Out – which we finally managed to open in December 2020 – bags have a double nature: not only practical, but also deeply symbolic. During lockdown people have had limited occasions to use handbags in their own homes yet buying these statement accessories has provided a certain comfort in the hope that they may be used again in public soon.

The pandemic has certainly influenced the type and number of necessary items we carry every day. From face masks to hand sanitiser, gloves and other items of personal protection, we now need more spacious and practical bags to fit it all in. A parallel with the 1940s gas mask bag displayed in the exhibition comes to mind. This handbag was designed to elegantly and efficiently house a bulky gas mask bag. Carrying such masks was compulsory during the Second World War and it is a stark reminder of life lived during the constant threat of poisonous attacks.

The pandemic has shown us a fluctuation in how bags perform economically, a shift in their symbolic meanings, but also a different path for more sustainable accessories and fashion consumption. The ‘buy less, wear more’ motto has gained popularity in 2020 and consumers have shown more sensitivity towards the makers and materials of their purchases.

What does this mean in terms of the future of the bag? My hope is that we will buy fewer, more durable bags that can be kept and used for years to come. Made with sustainable, upcycled or waste materials, these bags can enable our fashion choices to be kinder to the planet and to our wardrobe’s capacity.

Given by Jo Ani (V&A: T.176-2019)

Kent, UK (V&A: T.278-2019)

Further reading:

‘The Phantom Handbag’, Lou Stoppard, the New York Times, July 15, 2020.

‘The Return of the Luxury Handbag’, Isabelle Gerretsen, BBC.

‘Big Bag Theory: What’s the Status of the Bag in the Midst of a Pandemic?’, Tanya Mehta, Grazia, 16 September 2020.

‘Lockdown Clothing: a project documenting how we dress at home’, Rarely Wears Lipstick.

‘The Once and Future Handbag’, Vanessa Friedman, The New York Times, 10 December 2020.