The V&A exhibition A World to Win: Posters of Protest and Revolution is currently on display at the National Print Museum in Dublin (17 September – 8 November 2015). In this guest post, Eimer Murphy reflects on her experiences of researching Dublin protest graphics from the Students Against the Demolition of Dublin (S.A.D.D.) to a first-hand account of one of the recent Irish water protests.

Last year, I finally gave in to an idea which had nagged at me for several years and enrolled in a part time M.A. course entitled “Material Culture, Design History” in Irelands’ National College of Art and Design. I spent much of my first term time being thrilled and terrified in equal measures to find myself studying again after a 20 year gap. Essays! I had forgotten about essays…

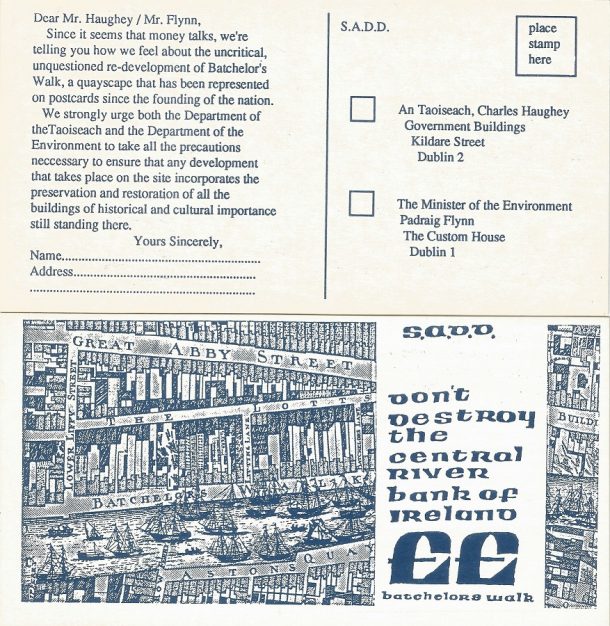

Our first essay was to be an object analysis. Our tutor, Lisa Godson, took us to the Little Museum of Dublin and asked us to pick one object from the thousands on display. It was important, Lisa explained, to pick something which would capture and hold our interest, since we would be writing seven thousand words about it. Try as I might to resist it, the object which immediately grabbed my attention seemed, to me, to be a poor choice. It was a small postcard, a simple graphic printed in blue ink onto light card. That’s it, described in only 15 words, so rather than submit the shortest essay in history I looked for a more complex object to analyse, but I kept being drawn back to the postcard. Its’ message intrigued me, as it happened to connect directly with my experiences of college the first time around, when I moved up to Dublin to study in the late 1980’s.

The card was made in 1988 by a protest group called Students Against the Destruction of Dublin (S.A.D.D.) as part of their campaign to highlight the appalling decay of the once-grand Georgian Quays, under threat by years of neglect and a series of proposed developments in the city centre. Click here for more information on S.A.D.D and the postcard campaign.

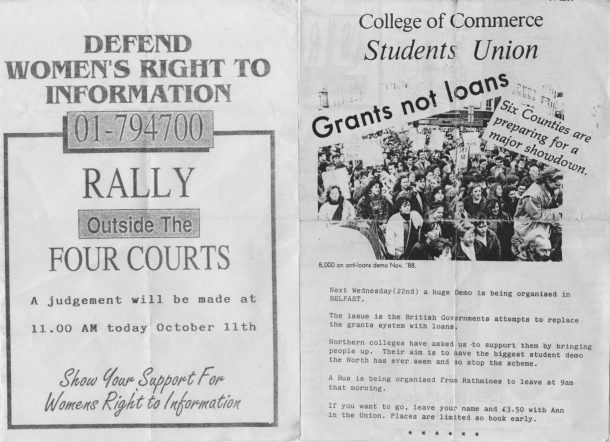

S.A.D.D, however, were only one of many student activist groups vying for attention in my first year, (1989-1990). Vocal student movements opposed increases in fees, cut backs in services, and a proposal to introduce student loans to replace student grants. More significantly, 1989 was the year that a high court injunction was taken against the Union of Students in Ireland (USI), who had published abortion information in their student welfare handbooks. Student bodies were fighting back and there were loud protests on Dublin streets, it seemed, every few weeks. It all had a profound effect on me, so much so that I wrote my first Politics essay on the student protest movement, connecting what was happening around me with the wider global protests of that year.

So here I am; it’s twenty years later, I find myself back in college and once more protests fill the streets. After years of enduring austerity with surprisingly little coherent protest, it is the prospect of paying metered water charges that is finally uniting people to take action. As the Government sets up its’ new utility, (the imaginatively named Irish Water), public opposition grows, and large demonstrations are becoming a regular occurrence. So it feels almost eerily inevitable that I should write on a protest object for my first college essay this time around.

During my research I was lucky enough to travel to the V & A in London to see Disobedient Objects. The curators had collected objects made for and during protests from all over the world; I found it fascinating. One corner of the exhibit was left empty to allow members of the public to add objects relating to ongoing global conflicts. I had a copy of my protest postcard with me and I put it up there (delighting ex members of S.A.D.D. when I told them that they now had work exhibited in the V & A.) I fully expected to see the Irish water protests represented by a flier or two, but surprisingly I found none. I remarked on this when I spoke to Catherine Flood, one of the curators of the exhibition. I then spent an entertaining half hour emailing her images and videos of the water protests until eventually she said “Why don’t you write a blog for us?” So here it is.

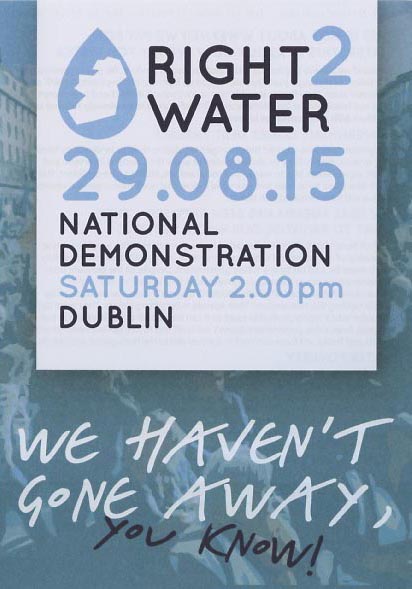

I have been on many of the water protests in the year since the movement began; the first nationwide demonstration took place on October 11th, 2014. What is striking about them is the good humour of those taking part and the sheer inventive genius of the objects they make and bring with them. From the young boy who carries an enormous replica of a stripy plastic drinking straw with a sign declaring “This is the last straw”, to “the Tapman” who wears a home made water tap on his head, people seem to go to enormous time and trouble to make thought provoking and clever objects specifically for these demonstrations. So, armed with my camera, I went on the last big water protest on the 29th of August to attempt to capture images of some of these objects and discover what motivated their makers to create them.

The by now established route for the water protests is along the banks of the river Liffey (the same section of the Quays mentioned in the S.A.D.D postcard). On march day I headed to Heuston Station where a large crowd had already gathered. The sun was shining but inky black clouds were already forming over Dublin Bay as we waited for the whistle to signal the start. Since the earliest days of the anti water charges campaign, one thing has become unavoidably clear; namely, the power of social media to organize and mobilse people.

There are hundreds of anti water charge groups all over the country, but one, the Right2Water Community, has become the umbrella group which co-ordinates the others for these National protests, and it does so largely through social media. On the 29th Right2Water hand out printed balloons as people arrive on buses and trains from all over the country, forming up behind their own identifying banners; county, political party, union and even sports club banners are utilized. Many groups print out official placards and posters but it is the individuals with their home made objects that interest me more.

The whistle blows and the crowd cheers as we begin to move. People are tightly packed and I have a couple of epic fails as I spot objects and try to fight my way to them, only to lose both the object and my own group. It’s not at all intimidating however. There is much chat and banter in the crowd; one man carries a complicated contraption which looks like a fishing rod with a carrot on the end; he also carries a placard which, presumably, explains it all, but try as I might I can’t get over to him. In desperation I try to raise the camera over the crowd (not easy when you are 5ft tall). He spots me and roars “ah here, it’s two euro for a photo of the carrot!” to the amusement of everyone in earshot.

Just ahead of me I spot a group with home made signs and I hurry to catch them. Unfortunately I didn’t catch their names, but along with signs referencing Fr. Ted (“Down with this sort of thing” and “Careful now!”) which are regular features now of any Irish protest, one is carrying a message devastating in it’s simplicity:

When I asked why he had made the sign, he said; “It does what it says on the tin”. Fair enough.

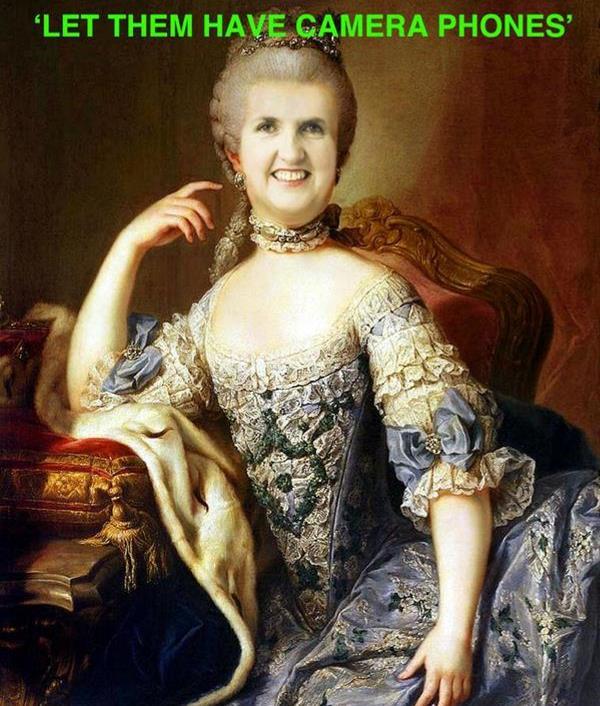

Beyond this group I can see a placard making fun of our Tániste (deputy prime minister) Joan Burton. Early on the campaign Ms. Burton made an epic fail of her own when she remarked that, although water protestors claimed not to be able to afford to pay water charges, they nonetheless seem to be able to afford smart phones with which to film acts of protest to post online;

All of the protesters that I have seen before seem to have extremely expensive phones, tablets, video cameras. There has been the most extensive filming in relation to any of these actions that I have ever seen anywhere. Hollywood would be in the ha’penny place compared to what’s done here, (Deputy Joan Burton).

Never underestimate the wrath of an internet scorned; unsurprisingly, social media erupted; first with angry tweets and messages, and later with memes such as this one:

One protester took Ms. Burtons’ words to heart and used his Hollywood skills to great effect. At the next protest he asked people to “wave your phone to Joan”, filmed their reactions, and created this youtube video

The internet has become the modern equivalent of the 18th Century print shop window, and memes, gifs and videos appear online in reaction to any political event with a speed that would have made Gillray, Cruikshank et al green with envy.

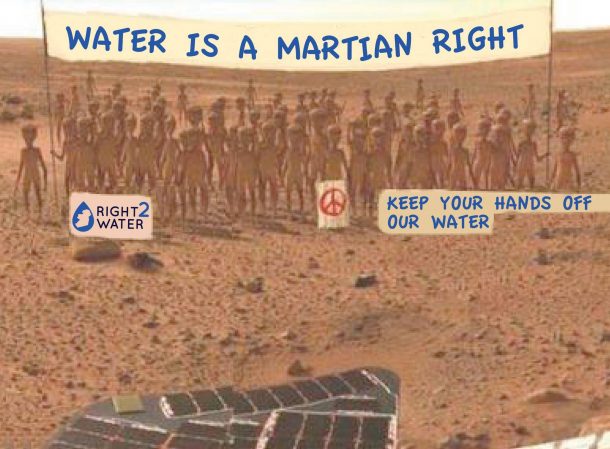

For example on Monday, 28th September, NASA held a press conference announcing that they had discovered evidence of water flowing on Mars, and mere hours later this had appeared on social media.

Back to Ms. Bruton, represented on this placard (below). The message contains a popular pun on water protests; the word “fluich”, (the Irish word for wet), rhymes with “puck”. Brilliantly this protester has also taken steps to protect his placard against the “fluich” with clingfilm, a must on any Irish protest.

As we move along the Quays the protesters chant: “no way, we won’t pay!” and “from the river to the sea, Irish water will be free”. At one point a protestor leads an entire section of the march in a rousing rendition of “It’s a long way to Tipperary”.

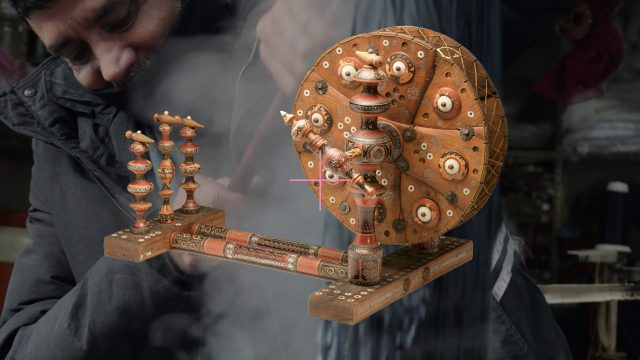

Ahead of me, right against the quay wall, I spot a fantastic object sparkling above the crowd and am determined to get this one. I break away from my group and fight my way over and finally, I catch my first object. It is being carried by its’ maker Eileen Stephens, and is her interpretation of an elemental symbol for water that she found online.

(Photo: Eimer Murphy)

I asked Eileen what motivated her to make an object, why not just draw the symbol on a poster? She tells me that she is a community worker, and as such she is “used to making things for pageants and plays”, an answer which highlights the links between protest and pageantry. Moreover it turned out that water and water rights are deeply connected to her family history. Her father, Ambrose, had an innate knowledge of where the water tables lay, and helped local farmers to find springs and water sources and “was teaching people about sustainability and setting up local water sharing schemes since the 1960’s”. Eileen feels that charging for water goes against her fathers beliefs and the community spirit that he worked for, and as a maker, she uses her tried and trusted materials (paper, wire, paint and ribbons) to eloquently express her opposition to the water charges with an eye catching and deeply personal symbol.

As I caught up with my own group, the black clouds were gathering and the first huge raindrops began to fall. At the risk of making it sound as though the water protests are scripted by Roddy Doyle, I must report that the instant the first drop hit the ground someone shouted “it doesn’t fall from the sky you know!” to roars of approval and laughter from the crowd.

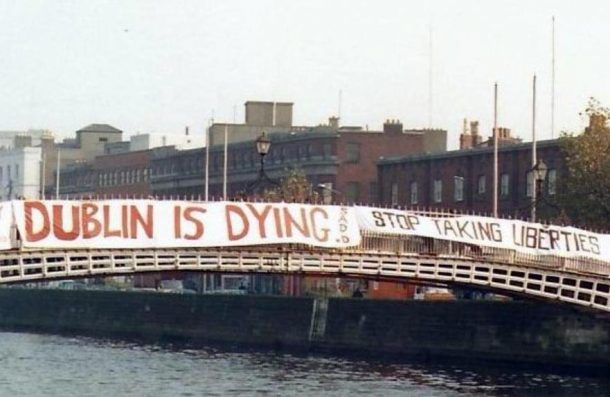

Up ahead is the Ha’Penny bridge, wearing it’s own banner for the day. This footbridge is often used by protestors; back in the 1980s banner wrapping the bridge was a favourite tactic of the Students Against the Destruction of Dublin.

(Image: Ciaran Cuffe.)

By now we were turning onto O Connell Street at the end point of the march, where the stage was set up at the General Post Office (GPO) for the speeches. There are many Greek flags flying in the crowd in solidarity with the Greek people.

My partner (who is much taller than me) suddenly points to something I can’t see; he tells me that he can see someone wearing some sort of head-dress in the distance. I push through the crowd and there he is; The Tapman! His name is Noel Carter and he is from Drogheda, Co. Louth. As soon as he sees my notebook he asks “what paper are you from?” I take it that means that many reporters have spoken to him about his headwear; “Ah yes, I’ve been photographed in this one many times” he says “I’ve been seen in papers all over the world”. It is made of a combination of plastic plant pots and pipes glued together, with dowel and plastic golf balls on top, and he wrapped the whole thing with duct tape. I ask him how he came up with the idea and he tells me that he was at the first of the water marches and saw the efforts other people had made; he went home and as “a bit of a handy man” he thought he’d try to make something himself. The shape of some things he had “lying around” lent themselves naturally to the basic tap shape and he worked it out from there. He has worn it to every major protest “It was silver first, and then I painted it green for St. Patricks’ Day, and for the march close to Christmas I painted it red. When the charges are scrapped, I’m painting it gold”.

Delighted to get to talk to The Tapman, I look around for my next object, but just then the black clouds cracked open and the rain poured down. We ran to take shelter under the portico of the GPO, where I met this gentleman:

He is carrying an old battered aluminium kettle on a string around his neck, covered in worn old protest stickers: “I use the stick to bang on it, to make a bit of noise,” he tells me, lifting it up to show me the underside, battered completely concave so that “if it rains, I can wear it as a hat,” he says, putting it on his head to demonstrate, and then, with eyes full of mischief he adds; “or I can hold it out to fill it, and make a free cuppa when I get home”.

Looking out on O Connell Street rain is so heavy it is drowning out the voices of the speakers on the podium, despite the PA system. Protesters are running in all directions; many using their placards as makeshift umbrellas. The heavy rainfall ably demonstrates one of the reasons why water charges are so unpalatable to the Irish people; as one banner puts it “I’ll pay for water when God sends me a bill”.

As an act of civil disobedience peaceful, organized demonstrations may seem quite tame, but there is something powerful about taking to the streets; the spectacle of hundreds of people all moving together cannot but have an impact, for both participants and observers. Recently I was speaking with Sabine D’Argent, a French born designer resident in Dublin, about the power of parades and pageants. Sabine is the designer of the St. Patricks Festival outreach group City Fusion/Brighter Futures. Every year they take hundreds of children from Community groups all over Dublin, and dress them in Sabines’ fantastic costumes, hair and make up, to perform in the St. Patricks Day Parade. As Sabine puts it:

Usually, it is the important people, the King or Queen, who parade in the street with all of the people waving and cheering. But for these kids, for one day, they are the King. They have taken over the streets, and everyone is looking at them, waving and cheering. And I think it has a huge impact on their confidence; it changes them. I know it does.

(Sabine D’Argent, March 2015)

Many of the water charge protestors interviewed say the same thing; that they have never been on a protest before. That this issue has brought them out onto the streets, time and time again over the past year, in huge numbers, is a demonstration of how deeply felt is the opposition to these charges. Interestingly I have noticed that those who carry a physical object tend not to shout slogans as much as those who don’t. Their objects are a physical expression of their opposition, and the uniqueness of their homemade objects enliven the protests just as much as the shouting and singing.

Eimer Murphy, October 2015