1871-2021: The Royal Albert Hall’s 150th Anniversary.

In the last two and a half years I intensively researched the history of the Royal Albert Hall, I now want to share my discoveries. I will dedicate this innovative building a series of blog posts.

Throughout the year I will uncover and celebrate different aspects of what has become a landmark. A symbol not only for London. Globally, it is well-known as an extraordinary venue for a wide range of exceptional performances and cultural events.

As a starting point I will use news stories published back in 1871 about the Royal Albert Hall. What did contemporaries think of the new building? Which aspects captured the imagination of the general public and the attention of specialists? What facets triggered debates or were taken as a basis for satire?

January 1871: Enthusiastic Press for The Great Organ at the Royal Albert Hall

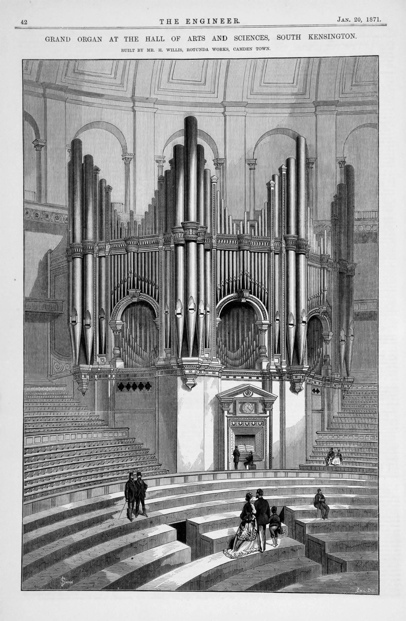

At the beginning of 1871, the press took a great interest in the Albert Hall’s organ. Specialists and the general public were both eager to know more about the instrument under construction. The cost of the Albert Hall’s organ was a whopping £8000, 4% of the total cost of the entire building.

They described the organ as the largest in the world and one of the finest in Britain. Its builder was already well-known. Mr Henry Willis had constructed the famous organ at St George’s Hall in Liverpool (fig. 2). Furthermore, Willis had designed an impressive one for the Crystal Palace, Alexandra Park.

A Technically Innovative Instrument

The specialised technical press gave the Great Organ at the Albert Hall ample space. They were enthusiastic about the ‘gigantic instrument’s’ technical specifications.

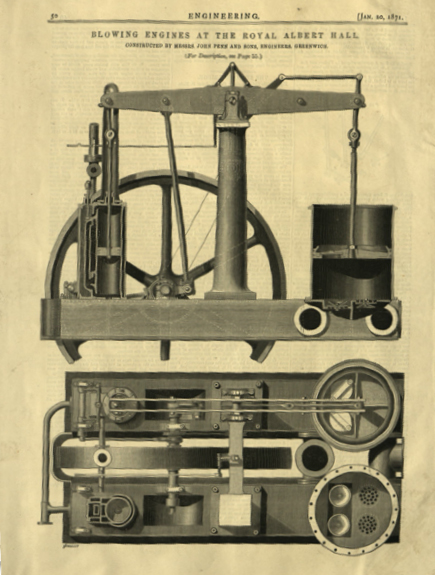

The organ boasted six pairs of bellows or ‘feeders’ and a pair of blowing engines (fig. 3) which supplied wind to the organ at high pressure. As the journal Engineering commented:

Great advantages appear to result from this arrangement, as, in the first place, no effort is demanded of the performer to open and abut the slides; and, in the second, the instrument is disencumbered of an immense amount of lumbering machinery.

[‘The Royal Albert Hall Engines’, Engineering, 20 January 1871, pp. 55-56]

It has been observed that the Albert Hall’s Organ’s innovative technical solution resembled in many respects the scheme of the organ of St Sulspice in Paris. This had been built in 1861 by the great organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (181-1899), who would go on to design the organ for Manchester Town Hall, in 1877. It is not clear if French precedents influenced Willis.

Willis worked with Messrs J. Penn & Son. These well-known Greenwich based engineers specialized in maritime engines. They had won prizes at the 1851 exhibition. The firm, in fact, especially designed and manufactured the Albert Hall’s engines.

A ‘novel’ appearance

Innovation did not only characterise the organ in technical terms. Importantly, the instrument was also an aesthetic novelty. Contrary to general practice at the time, the Albert Hall organ does not have a proper case.

Its appearance is dominated by its structural features. The outer pipes, burnished and polished, became ‘the chief ornament’. As the journal ‘Engineer’ observed:

a new principle is developed in its design, the object of which is to enhance the effect of the internal pipes by leaving them unobscured by those usually placed in front

[‘The Grand Organ of the Hall of Arts and Sciences, South Kensington’, The Engineer, 20 January 1871, pp. 39–40, 42]

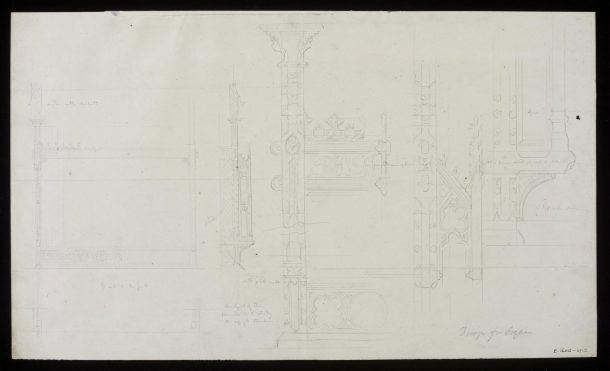

Architects design organs

In this period, the outer shell of an organ was often designed by architects. In the V&A’s collections there are a number of drawings testifying to the activities of well-known figures of the time in this field. An example of this is a design for an organ case by Philip Webb (1831-1915), dating to the same years as the Albert Hall’s one.

The V&A collections feature other interesting organ designs. One was a collaboration between the architect and pioneer of the Gothic Revival A.W. Pugin (1812 – 1852) and the well-known interior decorator John Gregory Crace (1809 – 1889), fig. 4.

Fig. 4: Design for an Organ, pencil drawing on paper, A.W. Pugin (1812 – 1852) and John Gregory Crace (1809 -1889), ca.1851, V&A Collections, E.1602-1912

John Gregory Crace was part of the Crace family firm. The business worked for every British monarch from George III to Queen Victoria. They were the most important interior decorators in Britain in the 19th century.

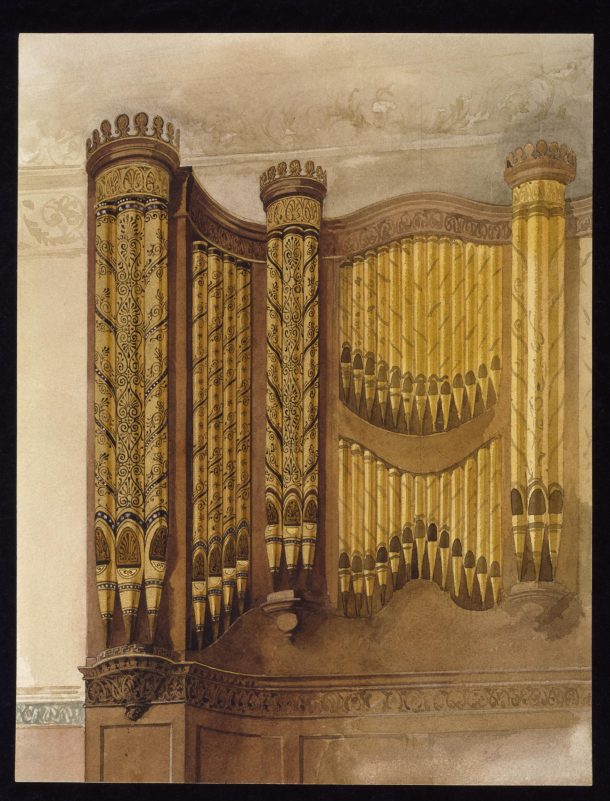

The watercolour in fig. 5, dated to the 1880e, shows an organ design by John Dibblee Crace (1838 – 1919). He first came to public notice through his Gothic- and Renaissance-style furniture for the International Exhibition of 1862.

The more elaborate nature of the organ cases in these example, showcases the distinct character of the solution chosen for the one at the Royal Albert Hall.

To know more…

This blog post is one of the outputs of the research project Designing the Future: Innovation and the Construction of the Royal Albert Hall, generously funded by the Leverhulme Trust. To learn more on this topic and the history of the Royal Albert Hall see the monograph ‘The Royal Albert Hall: Building the Arts and Sciences’. Which will soon be available.