Being Italian, I always felt secretly chuffed when I passed by the V&A Cast Courts and saw the plaster replica of Michelangelo’s David standing there: who better than him could watch over other reproductions of medieval and Renaissance masterpieces from the Bel Paese?

Imagine then how thrilled I was when I was asked to perform the scientific equivalent of exploratory surgery on the surface of the David! As our expert conservator Johanna Puisto planned the cleaning of the surface of the statue (see her blog), we felt it necessary to find out what type of surface finish and paint had been used over the years on the David, and see how many times the surface of the plaster had been repainted since the construction of the cast.

On a cold morning in October 2013, Johanna and I donned our safety boots, climbed the scaffold that had been erected around the cast and started our inspection of the David. We were looking for existing areas of surface damage (Figure 1): these would be the perfect place to remove small samples to be analysed in the V&A Science laboratory.

Think of it as a plaster cast biopsy! In the end I took three small samples, two from the hair curls and one from the upper right thigh of David (see Figure 2). The samples were approximately 1 mm across and contained all the paint layers down to the plaster substrate, the ‘core’ of the statue.

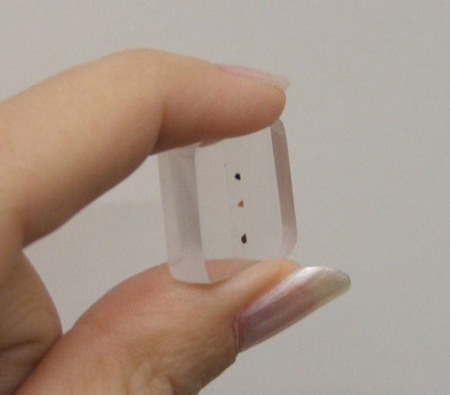

I embedded them in clear polyester resin (figure 3) in order to inspect the layer structure of the paint.

Figure 3: Samples embedded in polyester resin.

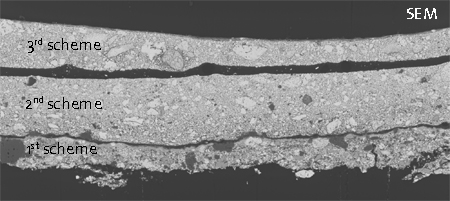

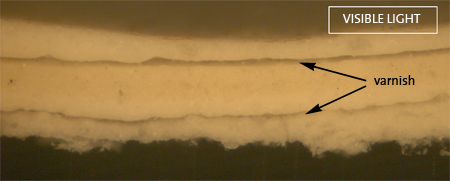

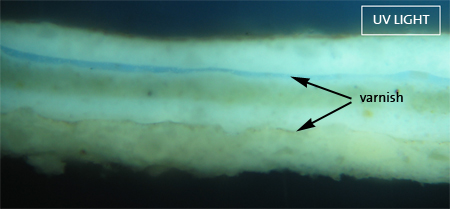

I viewed the samples under a microscope with white light and ultraviolet light (Figure 4), and then I also brought them to the Natural History Museum for analysis with one of the scanning electron microscopes (SEM/EDX) there.

The samples showed very clearly that three paint schemes, each with its own layer of transparent varnish on top, are present on the surface of David (Figure 5). The SEM/EDX experiments suggested that the white pigment lead white is the main component in all these layers; lead white is mixed with other materials such as barium white (another white pigment in use from the second half of the 19th century), gypsum and possibly chalk.

Two of the samples also had a very thin brownish layer on their surface, probably a diluted wash of brown ochre used to tone the current surface of the statue, providing subtle modelling for David’s rippling muscles. All the materials identified in this study were regularly used from the mid-19th century onwards, therefore we cannot date the layers precisely. Additionally, the presence of varnish in between the paint schemes suggests that each layer represents a different stage in the appearance of the statue.

Johanna was happy to hear the results of the analysis as they helped her understanding what she was going to be cleaning, making sure David would look his best at the end of the process: it is important to know when lead paint is present on an object, as it is a hazardous materials and needs extra precautions. Besides, it was very satisfying to find out how many layers of ‘skin’ David has, and all in a day and a bit’s work!

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Dr Alex Ball and his team at the Natural History Museum for granting me access to one of their SEM machines.

Very interesting read. I was playing a game called “Cities Skylines”, a modder has recreated the statue digitally for the game. I was looking at the statue, and though I would do some research. Thank you.