In the age of coronavirus, with so many employees working from home and city centres deserted, questions have been raised whether the coffee house in its modern form can survive. But the coffee house is a rather resilient beast and has seen many changes in the last 350 years. Coffee drinking, along with lighting a small fire in a ceramic pipe for smoking and wearing wigs for fashion’s sake, was a habit developed in the seventeenth century. And like the other two, it’s one whose adoption would not at first glance seem very desirable. Why would you want to ingest a hot bitter drink at regular intervals?

Yet the coffee house has also far outlasted the fads of wigs and pipes. Since its seventeenth-century inception, overseeing the rise of newspapers, insurance companies, and copious quantities of literary gatherings and political intrigue, it has evolved significantly. The coffee chains that dominate the British high street today seem a far cry from their mid-seventeenth-century coffee house antecedent.

Coffee trees grew wild in Ethiopia, and the plants made their way to Yemen by the late Middle Ages. By 1600, drinking coffee was a popular pastime across the Ottoman empire, from Hungary to the Persian Gulf. Several decades later, coffee drinking established itself in ports that traded in Turkish goods, such as Venice, Amsterdam, Marseilles, and London.

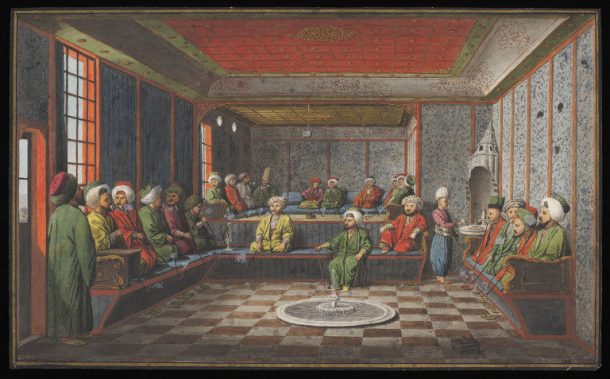

The European coffee house was modelled on its Ottoman counterpart. It was a male-only space, in which cups of coffee would be provided to patrons. They became widely popular. By 1700 London was replete with them, as male patrons combined pleasure and business when visiting their favourite coffee house. They were at the centre of political, religious, literary, scholarly discussion. There was also space for leisure activities such as cards, dice, and billiards. Although coffee was the main item on the menu, coffee houses might also serve tea and hot chocolate, and some offered meals. A seventeenth-century coffee house would likely be very unsuitable for our current Covid-19 environment, with patrons sitting close together in a small space, and often engaged in animated discussion.

Women were excluded from this male domain in most European countries, as it was considered an indecorous space. Usually the only female present might be the proprietor or the person serving the coffee. Chocolate houses on the hand were spaces where respectable women might visit during the day. And the private consumption of coffee in the home was growing apace.

The convivial space of the coffee houses plays an important part in late Stuart and Hanoverian political, intellectual, and economic history, but by the end of the eighteenth century they had fallen into decline. The rise of teahouses, which attracted a mixed-sex clientele and private clubs, which eliminated the inclusive nature of coffee house patronage, contributed to their decline in the United Kingdom. But they continued strongly on the continent, and played their role, from a site of political subversiveness during the Italian Risorgimento to the Viennese coffee house as the centre of Austro-Hungarian intellectual life.

In Britain, the nineteenth century saw coffee and bread as the main meal of the working class, with coffee’s stimulative nature curbing exhaustion and hunger pangs. Temperance houses in cities, set up by religious organisations to discourage the consumption of alcohol offered coffee to their visitors. On the latter point, the popularity of coffee drinking in the USA increased exponentially with Prohibition in the 1920s as people sought other stimulants. Private consumption of coffee continued apace, although tea was still the preferred beverage at home. Coffee was also served in hotels, restaurants, and refreshment rooms.

The twentieth century saw the introduction of the social practice of the coffee break in workplaces, which would be instituted in labour legislation in many countries. Workers would break at mid-morning (and often mid-afternoon) to consume a hot stimulating beverage.

The quality of twentieth century coffee in Britain was poor, and ‘coffee essence’ (flavoured with chicory) was a widely-used substitute. The demand for quality coffee in Britain went hand-in-hand with the rise of Italian-owned espresso bars in the 1960s, starting in Soho in London, as the new-fangled espresso machines led the way. The British preference for milk in hot beverages also saw the emergence of the cappuccino as one of the most popular drinks on offer. These espresso cafes usually only sold coffee, cakes, and sandwiches.

By the 1990s, there had been a transformation in the nature of coffee shops. The trade would soon be dominated by major coffee chains (Starbucks, Coffee Republic, Caffè Nero, and Coffee Republic). The most famous of them, Starbucks, an icon of globalisation was the last to appear on the British scene, with the first of its British cafes opening in Chelsea in 1998. By 2020 there would be nearly a thousand Starbucks Coffee in the UK. A wide variety of combinations, blends and flavours are products offered by these chains, so that the consumer learns a complex Italian-American nomenclature for different varieties of coffee, a far cry from ‘Black or White?’ offered by the average British cafe decades before. Starbucks claimed that their coffee shops were a ‘Third Place’, a location between home and work. Comfortable sofas were placed in the interior, to encourage a longer stay (and additional purchase of beverages). The coffees offered in these chains were more expensive than a cup in a cafe, but they promised a greater variety of options and often stressed the quality and origin of their coffee beans.

In the 21st century, Wi-Fi became standard and customers might use these coffee chains as an ad-hoc office space thanks to portability of the recently developed laptop. There was none of the conviviality of the early coffee shops. People might congregate in small groups or else drink their coffee alone, perhaps with headphones on and absorbed in a smartphone to drown out the rest of the world. At the same time, in offices, lunch time became shorter and shorter and speed was desired. Workers might purchase a hot beverage and sandwich to eat at their desk. A takeaway coffee carried in a plastic sealed branded cup became an icon of the white-collar worker. Likewise, the practice of bosses requesting that junior staff get them coffee (or coffee for the team) from a coffee chain, rather than the coffee brewed in house. Some decried the apparent presence of a chain coffee shop on every corner, but coffee was being sold in huge quantities. Getting a latte or Americano or espresso on the way to work was practically a daily ritual.

This all changed with Covid-19. As white-collar workers were encouraged to work from home, city centres became deserted. The plethora of coffee shops seemed grossly redundant. Even as Britain slowly opened up in the late summer of 2020, it was obvious that there was no going back to normal. Many workers continue (and are encouraged) to work from home. There is not only no need to pop into the coffee shop on the way to and from work and at lunch, but also the habit is slowly being forgotten. Many of the chains are making mass redundancies. What is the future for the coffee shop? Will the shuttered stores in city centres disappear but be replaced by more coffee shops opening in residential neighbourhoods? Well before the pandemic there had been a growing revival of independent coffee shops, offering high quality coffee to their patrons. Perhaps the coffee shop, true to its ever-changing history, will again transform itself into something else, catering to new needs and desires.

Further Reading:

Ulla Heise, Coffee and Coffee Houses (Schiffer Publishing Ltd: West Chester, 1987)

Antony Clayton, London’s Coffee Houses: A stimulating story (Historical Publications: London, 2003)

‘The Lost World of the London Coffeehouse’, Matthew Green, The Public Domain Review, 7 August 2013.

‘London’s Original and All-Inspiring Coffee House’, Amy Freeborn, Atlas Obscura.