Since the shutting down of most museums around the world in March and April, a major question has lingered about how we will make exhibitions in the near future – namely given lower projected visitor numbers and the need to maintain strict social distancing. Slowly, as institutions re-open their doors, many have been able to extend the runs of exhibitions that had initially been cut short by the virus, making the best of a bad situation. Work has also resumed on exhibitions that had already been in the works prior to the virus, but now with revised opening schedules. We will soon see what form these shows take, and how they will accommodate our new situation.

For the most part, however, these exhibitions – having been initially approved for the museum schedule years ago – are still a reflection of pre-pandemic realities. How will programming and the subject matter of exhibitions change in the future? V&A Dundee, in this regard, might offer some interesting insight. When they opened their doors again on August 27th they were one of the first in the world to debut an exhibition that was entirely conceived and created during the period of closure. Appropriately enough, the topic of the exhibition is the pandemic itself.

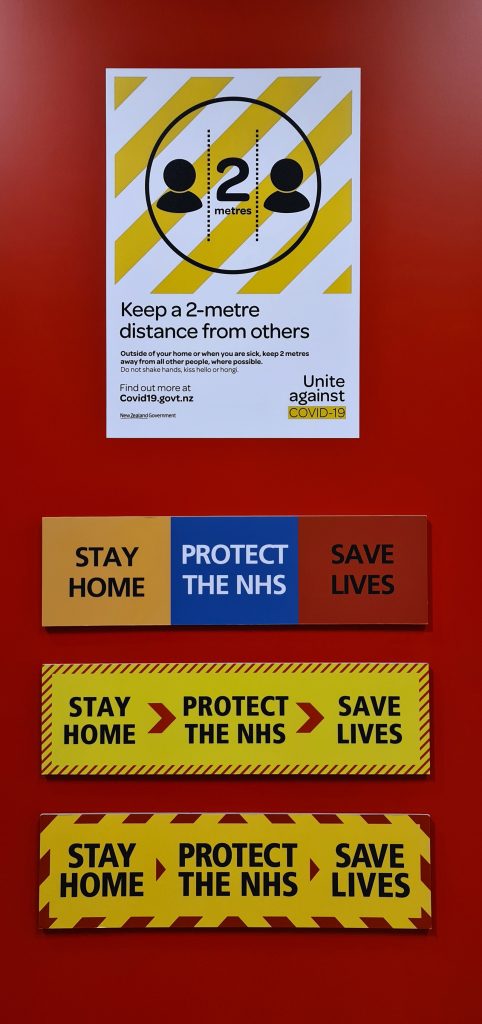

The idea for the exhibition, called ‘Now Accepting Contactless’, was first proposed by Sophie McKinlay, the Director of Programme, in late May as much of the museum staff were still on furlough. She felt it was important to concentrate the museum’s effort on his topic because, as she says: ‘As Scotland’s first design museum there has never been a more urgent need to demonstrate how design is central to all our lives. From the instruction of new behaviour to the wearing of face coverings to the redesign of hospitals to cope with the crisis Covid-19 has triggered a wealth of design initiatives to help us navigate a path through this new reality.’

But in order to pull together an exhibition in such speed and all while working from home, an entirely different way of working had to be constructed. Fortunately, by June more and more of the Dundee team were able to come off of furlough and a core group of six people working between Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Perth and Stroud, began with weekly video-conferencing calls, where each would pitch different object ideas to be included in the show. Once the key criteria for inclusion was agreed and a number of objects had been selected, certain thematic strands started to crystallize – such as ‘Instructing New Behaviour’, ‘Hacking Health Care’ and ‘The Home’.

From there, managing the workload was a matter of divide and conquer. Two-person teams were assigned to each of the eight overall themes, tasked with developing the themes into discrete sections for the exhibition. Team members didn’t just include curatorial staff, but involved staff members from across the museum, some who had never worked in curation before. The museum’s Young People’s Collective, who co-design and represent young people (aged 14-24) within the museum, were also given an entire section to curate. The video-conferencing meetings evolved to being a forum where each team could test out their ideas with the wider group for their respective sections.

Once the general structure of the show was set, curator Kirsty Hassard and assistant curator Lauren Bassam were tasked with overseeing the overall production of the exhibition. When asked how they dealt with the inherent sensitivity of tone needed in curating around such a delicate topic, Hassard says:

“Tone was discussed right from the outset of the project. We knew we couldn’t take an overly optimistic view on things – whereby we just celebrated the ingenuity of design. Some of the audience coming to the exhibition will have experienced personal loss, or be struggling with the precariousness of our times and it’s important to recognize that. We also wanted as much as possible to show the pandemic as a global experience, to amplify the voices of different communities, such as immigrants and NHS workers, whose experience of the last few months will have been dramatically different than others.”

Procuring objects has also had its challenges. In normal times, a curator might be expected to meet with potential lenders and see objects in person before deciding if they should be included in an exhibition. Here, that was obviously not the case; however the constraint was turned into an advantage, as unburdened from any possibility of travelling, the team was able to select projects from around the world – pieces coming from as far away as Bogota and Beijing – simply negotiating these loans over video-conferencing and email.

Another challenge of curating an exhibition about an event that is still ongoing is that other objects weren’t immediately available because they were currently in use. That was the case with the Coronavirus helmets worn by police officers in Chennai, designed to promote more awareness about the dangers of the virus. In this case, the artist, B Gowtham simply gave the team permission to create a reproduction version in Dundee for display, and provided images of the original helmet to be displayed alongside for context.

Finally, this is the first global pandemic to play out in the digital era, and many of the most interesting design responses to the virus have been online. The display of digital projects however is challenging, as it’s not always clear how best they should be represented (eg. screenshots, video, interactives). For this, Hassard and her team discussed directly with each maker how best to represent their work. For instance, working with information designer Federica Fragapane, they created a three-minute playthrough of the website she created for the Overseas Development Institute.

Museums are famously known as slow-moving institutions. To a large extent, such careful pacing is important, as with the long-term maintenance of collections, and the production of new academic insight. But, what the example of ‘Now Accepting Contactless’ shows is that museums also have an important role to play in being quick-footed and reactive to the world. In wrestling with the limited staffing and short timelines, V&A Dundee also point to curatorial tactics which might be useful in the future – such as in opening up the curation of ideas to a larger group, creating massively co-curated exhibitions. We still don’t know what curating in the future will look like, but at the very least, we can take heart in the fact that it’s still possible to conceive and develop new exhibitions, even while under the constraints of lockdown.

Thanks Brendan – that’s a compelling insight to such flexible and creative working on a huge and contentious issue, and it looks like a great job by all involved.

I’d love to see that exhibition at the South Kensington site, or at least a video walk-through by one of the curators (or perhaps a member of the Young People’s Collective).