I live in a 1970s ex-local authority flat in south London. It’s been 1.5 years since I moved here and what glorious – and warm – 18 months it has been. Safely tucked away between streets of beautiful Victorian terraces, a 1-minute walk to a well-maintained park within a local conservation area, my concrete corner of socialist utopian design enjoys an important legacy of 1970s municipal planning; it still relies on its original, communal central heating system, which thanks to a district boiler controlled by the local authority supports all flats in the building at the same time. It makes heating and hot water available to its occupants (council and private tenants alike) all year in exchange for a fixed and very affordable annual service charge (which also includes shared costs of building and communal garden maintenance). I haven’t given my energy set-up much thought when I moved here. But the pandemic-imposed winter of remote working made heating at home a hot topic. As colleagues joined Zoom meetings hugging their hot water bottles and ‘how-to-save-money-while-working-from-home’ features became this year’s must-read, my radiators remained comfortably warm and my bank account balance unchanged.

There aren’t many buildings like mine left in the UK – buildings in which everybody can afford to stay warm at home. In many local authority blocks, similar district central heating provisions are at risk or have already been replaced by individual boilers and metered energy systems. These transformations have little to do with infrastructural improvement. In moving away from state-managed heat available as public good and favouring instead provisions of heat as individual commodity, controlled by private energy suppliers, homes become both less affordable and less energy-efficient. A recent study of Churchill Gardens estate in Pimlico, one of the remaining London estates which also still enjoys a similar, publicly-owned heating infrastructure revealed that its Co2 emissions were 8-10% lower because of its reliance on the communal energy supply than if each individual flat in the estate relied on its own boiler and energy supplier. But communal heating in the UK has a bad reputation, in part due to its reliance on often outdated technologies and systems in need of maintenance, but perhaps most significantly due to its association with council housing and all that it stands for in the popular imagination today. Yet, we know that community heating delivers significant economic, environmental and social benefits. It is one of the most effective ways to reduce building-related carbon emissions, helps build sustainable communities and deliver affordable energy, significantly contributing to the elimination of fuel poverty and carbon reductions.

In many European countries, district heating is an infrastructural standard. In Denmark, for example, more than 70% of all homes are heated through communal, neighborhood heating networks (in contrast, only 2% of homes in the UK rely on them). But the Covid-19 crisis might play an important role in rethinking domestic heating standards in the UK too. In fact, this relationship between heating infrastructures and public health – and pandemics in particular – has a long history. Many transformations and innovations in architectural design and city planning introduced in the first half of the 20th century have their origins in the growing contemporary understanding of the relationship between living conditions and health. The early 20th century ‘fresh air movement’ proponents in the USA referred to unventilated rooms as the ‘national poison’, promoting access to windows in all habitable spaces as a building standard. Bauhaus is often understood as a movement focused on germ-free designs, promoting healthy housing for the future. And the ‘clean lines’ of the iconic modernist home originate in the tuberculosis epidemic of the early 20th century.

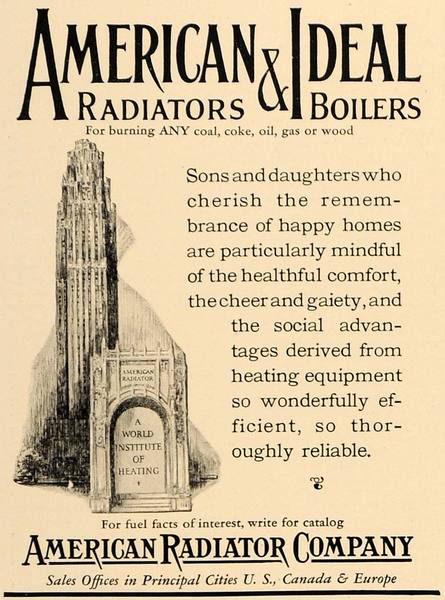

Some of the most notable transformations in thinking about home heating systems and their design date back to the outbreak of the Spanish flu in 1918, which brought with it the radiator as we know it. A steal, iron or brass radiator – a ‘hot box’ using water or steam to generate heat – dates back to the 1850s and this model of heating was a result of the contemporary theories of infection control. Like today, in the late 19th century health officials believed that fresh air could ward off infectious diseases. And while in the summer outdoor green spaces offered a viable, popular alternative to staying at home, in winter, spending a whole day outdoors proved a less attractive proposition. According to Dan Holohan, during the Spanish Flu epidemic the Board of Health in New York City ordered that windows should remain open to provide ventilation, even in cold weather (a recommendation familiar to anyone who might have attempted working in a shared office space in the last few months). This seemingly contradictory need for fresh air and heat at the same time proved an important factor in the transformation of radiator design. The new radiator still relied on the same steam-powered infrastructure but was made more powerful to keep spaces warm when windows were open during a very cold New York winter. Such robust steam boilers – often powered by local district heating systems, another design innovation of the period – became a standard not only in New York City but also in other northern US cities with colder winters, such as Chicago, Detroit, and Boston. And their effectiveness meant that the powerful American radiator also grew in popularity elsewhere (the American Radiator Company, the leading radiator manufacturer at the time, established factories in France, Italy, Germany, Austria as well as Hull, in the UK), fueling a major transformation on a large scale in ways in which homes were kept warm.

This thinking about heating provisions didn’t end with the pandemic. The mid-20th realization that universal access to heating didn’t just contribute to ‘better living’ but it also helped decrease winter mortality rates was fundamental to transformations in 20th-century housing policy and modern home design standards. Radiator heating systems started to gradually replace coal-fired open hearth heating systems in the first decades of the 20th century but became widespread in 1960s. And a radiator has become a permanent fixture in domestic space design. Today, in the UK around 95% of the population has access to central heating and half of all energy in the country is spent making heat. Yet, a recent IPOS Mori poll showed that more than 1/3 of the population describes their homes as cold and damp. Cold homes, a recent Public Health England report explains, are an important cause of winter mortality and morbidity, with residents of 25% of the coldest homes facing a 20% increase in risk of death during winter than those in warmest homes. And there is plenty of evidence that fuel poverty puts households at risk of the worst effects of Covid-19 (see End Fuel Poverty Coalition Covid-19 campaign). The combination of an increase in energy use – an inevitable outcome of a much greater reliance on domestic infrastructures during the pandemic – and reduction in income for many mean that radiators will remain cold this winter. Might it perhaps be time to return to the communal heating model for all, not as a manifestation of socialist utopian dreaming but as an infrastructure that makes warm and healthy homes accessible to all. As the current pandemic makes abundantly clear, access to heating that is reliable and affordable should never be a privilege.

Related Objects from the Collection

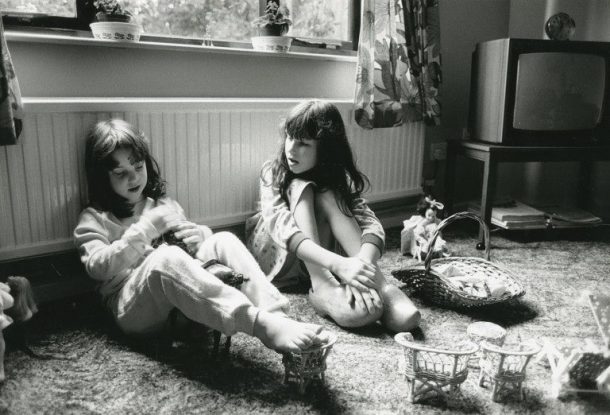

‘Reflecting’ (photograph), John Heywood, Northampton, 1984 (B.128-2013)

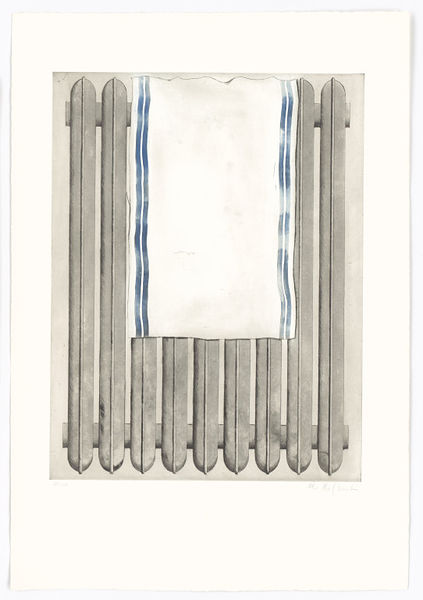

‘Central Heating with Towel’ (print), A. Hofkunst (E.41-1981)

Electric Fan Heater, Christian Barman for His Majesty’s Voice, ca.1934 (W.71:1 to 3-1978)

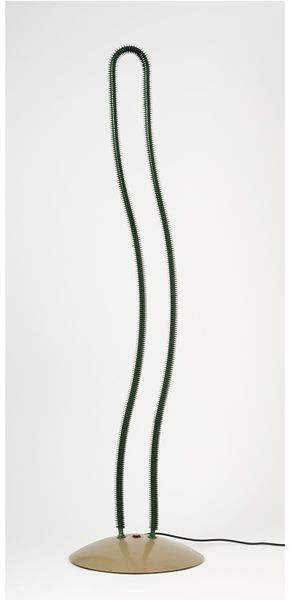

Cactus Radiator, Paul Priestman, Italy, 1992 (M.13-2006)