Exhibitions are the culmination of work by a large number of people, who bring their own knowledge, expertise and opinions to the table. In this post, three of the volunteers contributing to the Africa Fashion exhibition (June 2022 – April 2023) discuss their experience of working on the project.

Henry | Instagram @superglue_collective

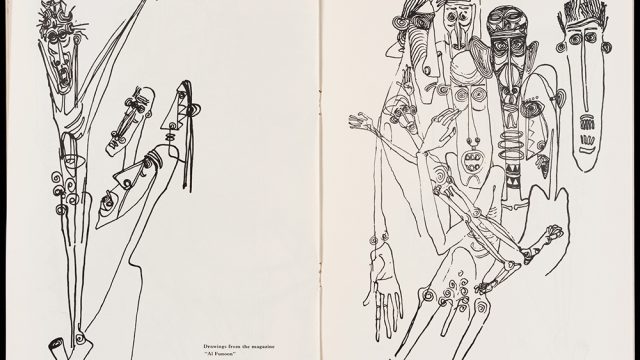

In producing Africa Fashion, the curators have been keen to collect inputs from a varied selection of voices. This has meant that I have been able to contribute my working, art historical knowledge of West African art into both the research and the curation of the exhibition. I am interested in moments in history at which art permeates the social, and in particular how the collective feelings of the public manifest themselves in artistic production, such as the pre-Colonial motifs that permeated Ghana after its independence in 1957. With this in mind, I have been exploring liberation movements in Africa during the 1960s, trying to find narrative hooks for the audience of Africa Fashion.

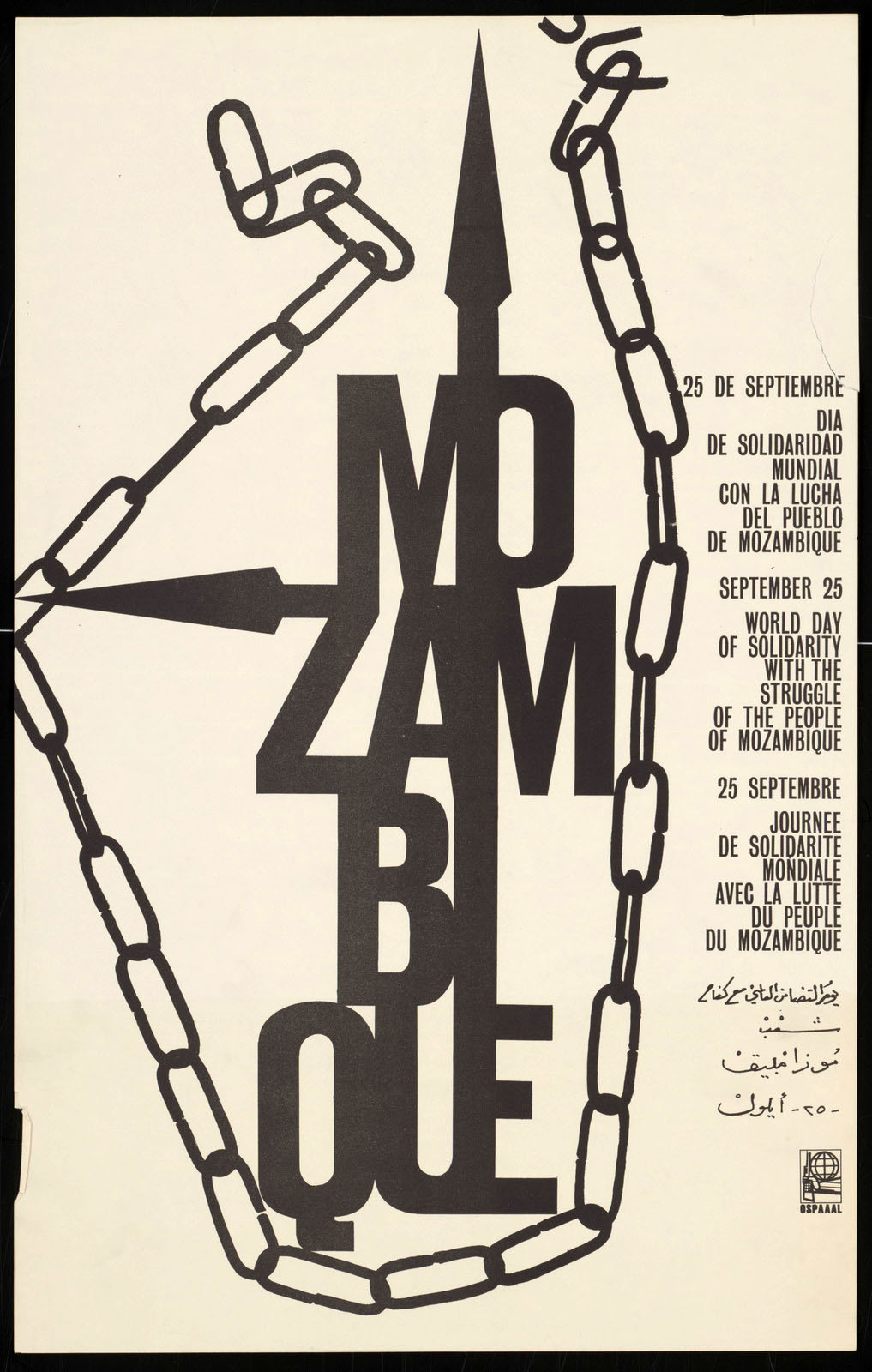

Two particular strands of research have become prominent; how can you possibly encapsulate each of the specific countries’ sentiments of liberation into the exhibition, and are there similarities between these concurrent cultural manifestations in the countries of Africa? I have been drawn towards pan-Africanism, an ideal that aims to unify people from African descent, which was championed by the first Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah. Pan-Africanism proliferated throughout cultural production during the 60s in West Africa – and was epitomised by the myriad, celebratory festivals held throughout the continent. Given their pan-African outlook and variety of art forms – along with the vast audiences they garnered – the festivals provided a crucible for arts and culture in Africa during this time. Alongside this I have been trying to uncover commonplace items, such as posters or music albums, that reflect the sentiments of liberation and independence within the public in Africa. As it turned out, I struggled to find collections of posters produced from the continent during this time, and instead was led towards a group of posters made by Latin American artists during the 1970s as part of the Organization for the Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL). The posters were made in Cuba, before being disseminated around the world, to garner support for African people in their fight against oppression. A collection of these posters are held in the V&A, and it has been interesting to delve into the different designs. In this poster created by Cuban artist Olivio Martinez, the artist has depicted Mozambique as breaking the chain link itself, alongside text that reads in a multitude of languages, aiming to bolster support for the struggle across the globe.

Samriddi

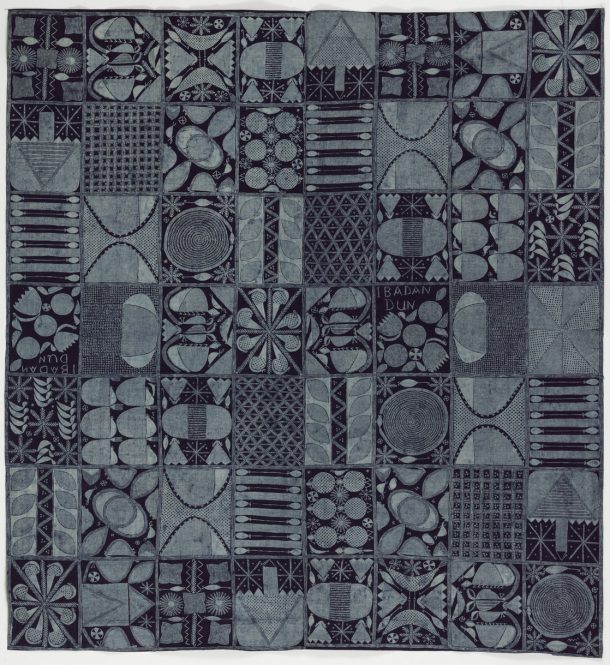

With a background in textile design, I was excited to research in-depth into Adire, an indigo-dyed cloth made and worn by the Yoruba people in southwestern Nigeria. I had previously only heard of this resist dyed textile in passing, and now I had the chance to use the V&A’s archive to dive deep into the world of indigo and the Yoruba people in Nigeria in the 1960s.

The indigo-dyed cloth is patterned through resist-dying techniques to create striking blue and white designs. The process is incredibly intricate, and there are various different forms of resist used to create the designs, from tying raffia to hand-painting starch patterns. More information about the process can be found here. The patterns and motifs can represent the maker’s identity, personal histories and, most importantly, reflects the evolution of this art. Making Adire is a skill that has been passed down through generations, each maker adds their story and perspective, while adjusting the cloth with the demands of the fast-paced world.

A lot of my research focused on how Adire was worn and used in 1960s Nigeria. The Horniman Museum’s archive of Nancy Stanfield’s photographs of Adire in Western Nigeria around 1966 was a fundamental source. The photographs show Adire worn in a variety of settings, typically worn by men and women, tied as a wrapper. For women it’s often worn with a blouse as well as a gèlè (headwrap). The cloth can also be used as a child carrier, so mothers could wrap their children around their backs for versatility. Adire is one cloth with multiple purposes, something special yet functional for everyday life.

Adire is a marker of the history and prominent culture of the Yoruba people. It highlights the loss of craft in today’s world, yet it also reminds us of the joy and importance of textiles. Understanding this significant textile and how it evolved during a developmental time in Nigeria, reminded me of my own Nepali heritage – and how indigenous crafts need to be celebrated worldwide.

Tosin | Instagram @africanstylearchive

The rich history of African textiles is hugely important to the exhibition, and research into textile production on the continent has been an integral aspect of thinking about Africa Fashion. My research background in documenting African fashion history naturally meant I gravitated more towards the social and cultural impacts of African textiles and their production processes.

I was excited to discover the Urafiki Textile Mill, which was based in Tanzania, East Africa. The mill produced local fabrics such as Kanga. Kanga is a rectangular printed cotton fabric that usually has a decorative border around the fabric, and often has a proverb on the bottom in Kiswahili. Kanga is an important medium of communication, and the text and design usually convey different messages for each wearer – this might be political, religious or social. This example in the British Museum collection says ‘MWANAMKE NI CHACHU YA MAENDELEO’ in Kiswahili which translates to ‘The woman is the catalyst to development’.

The Urafiki Friendship Textile Mill was one of the mills in Tanzania that produced Kanga in the 1960s. What I found particularly interesting about the mill – as well as the other prominent factories in Tanzania in this period – was its aim to promote a sense of national pride for Tanzanians by locally producing fabrics to be made into clothing for various occasions. The Urafiki Mill in particular employed a jazz band named the Urafiki Jazz Band, led by Juma Mrisho. The band, who dressed in Urafiki clothes, was formed to market the fabrics the mill produced. I found this marketing strategy employed by the factory so fascinating and innovative – it was a method that incorporated a national sense of pride and uniformity through fashion and heritage from the shirt styles that the band members wore to perform. The convergence of patriotism through fashion, clothes and music in post-Tanzania’s independence has been particularly enlightening for me, and I feel is important to document in relation to the exhibition.

Conclusion

These case studies and the multiple stories that can be told from them, echo the layered and interwoven narratives that Africa’s fashion creatives tell through cut, cloth and ornament, or via the shutter of a photographer’s camera. They give a taste of the richness, diversity and vitality of the fashion scene that we aim to celebrate through the Africa Fashion exhibition.