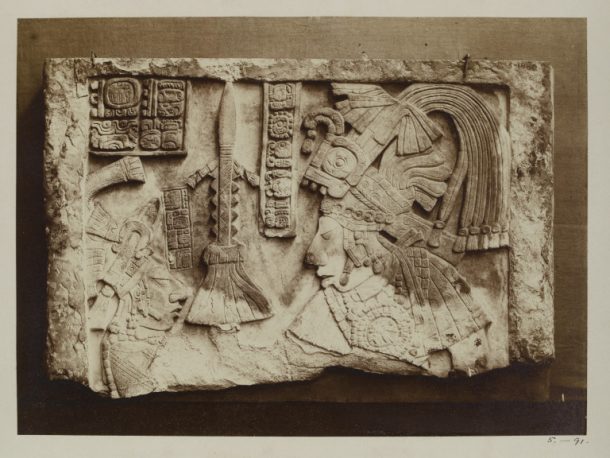

Albumen print from a gelatin dry plate negative. Photograph of a damaged panel carved with Mayan script and human figures, found on the banks of the Usumacinta River, Mexico

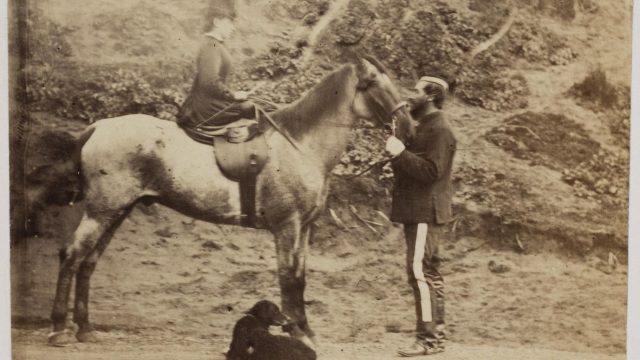

These striking photographs caught my eye recently, as I don’t normally come across material relating to the Maya in the Photographs Collection. Research showed me they were taken by Alfred Percival Maudslay (1850-1931), a British colonial diplomat, explorer and archaeologist who was one of the first modern archeologists to study the Mayan civilization. He began his career working for the colonial service in Trinidad, Queensland, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, but in 1880 he left the colonial service and first travelled to Guatemala. He explored Mayan ruins at Quiriguá and Copán with fellow archaeologist Frank Sarg, and travelled with him to Tikal. (Sarg also introduced him to Gorgonio Lopez, who went on to be his guide on many further expeditions). Maudslay was the first European to describe Yaxchitlan, and gained fame for his explorations of Chichen with Teoberto Maler.

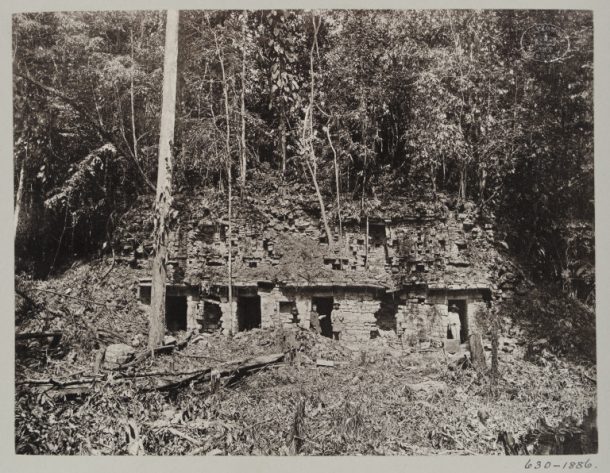

Maudslay used a variety of techniques to record his archaeological finds. He took photographs to record the sites he visited, and made good use of the new ‘dry plate’ photography process, which involved fewer chemical processes for the photographer to undertake at the point of capture, and was therefore easier to use whilst on expeditions.

Photograph of Temple A, Menché, Guatemala, taken by A.P. Maudslay

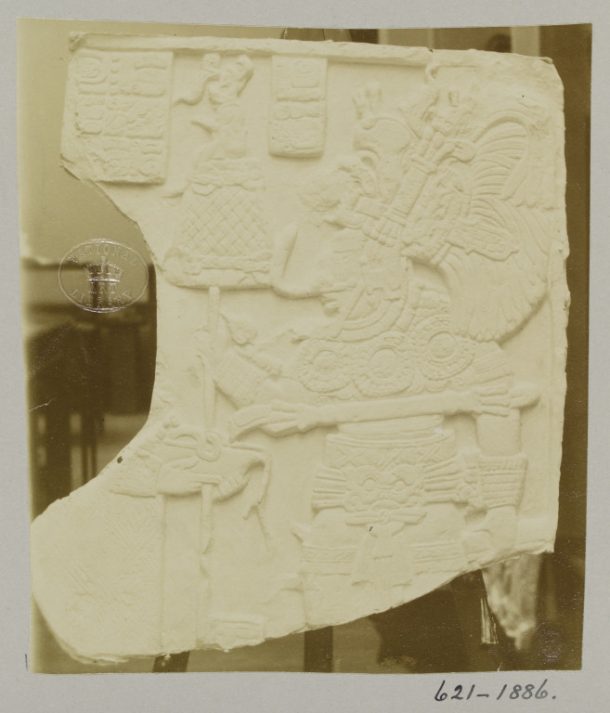

He also recorded objects by taking ‘squeezes‘ of carved surfaces. This was a process in which thin wetted paper was laid over the surface to be recorded and pressed into the indentations with a brush. Layers would be built up in this way and left to dry before removal, similar to papier-mâché. When the dry paper shape was removed it formed a negative mould of the carved surface, from which a positive copy in plaster of paris could be made. Maudslay and his team also took direct plaster casts from objects, where this was possible.

Photograph of a plaster cast of ‘The Turtle,’ Zoomorph P monument at Quiriguá, Guatemala, on display at the South Kensington Museum in 1894.

The plaster modeller Lorenzo Giuntini accompanied him on many of his expeditions, and in 1885 Maudslay persuaded the V&A (at that time known as the South Kensington Museum) to accept his finds, casts, moulds and photographs, and also to hire Lorenzo to make further casts from the paper moulds.

Albumen print from a gelatin dry plate negative. Photograph of a plaster cast of a bas-relief from Palenque in Mexico.

Unfortunately, the carvings, casts, objects and moulds took up a great deal of space, and over time were increasingly viewed as incongruous in terms of the rest of the Museum’s collections. They were eventually passed on to the British Museum, and a few are now on display there. Some of them are quite amazing in terms of the skill which must have been involved in creating the cast…

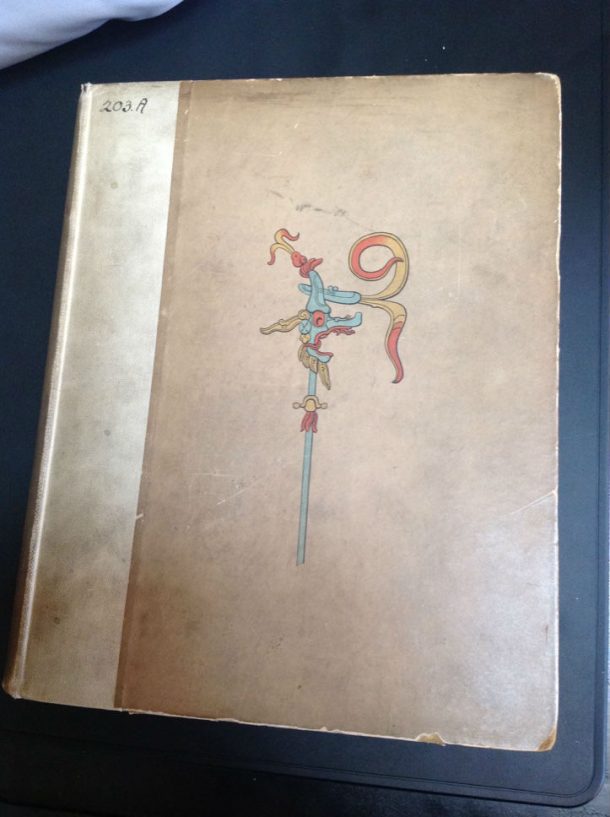

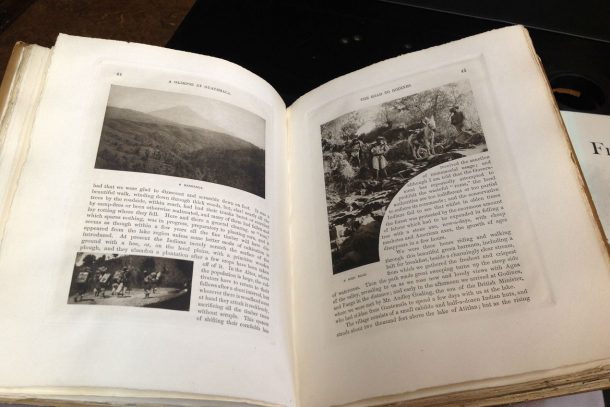

The photographs stayed at the V&A, however, and we also came to acquire other material related to Maudslay’s travels. In 1892, Alfred Maudslay married Anne Cary Morris, and for their honeymoon they travelled together to Guatemala, again accompanied by Gorgonio Lopez as their guide. The couple jointly wrote a delightful account of their trip, titled ‘A Glimpse at Guatemala’, which was published in 1899. We have a copy of this in the National Art Library at the V&A, and it is a beautifully crafted book.

It is printed on handmade paper, and includes photogravures of Maudslay’s photographs (and also some by Osbert Salvin), chromolithographs of drawings from photographs by Blanche Hunter, and maps and diagrams of the sites. The main account of their travels is written by Maudslay’s wife Anne, but her husband chips in every so often with archeological information.

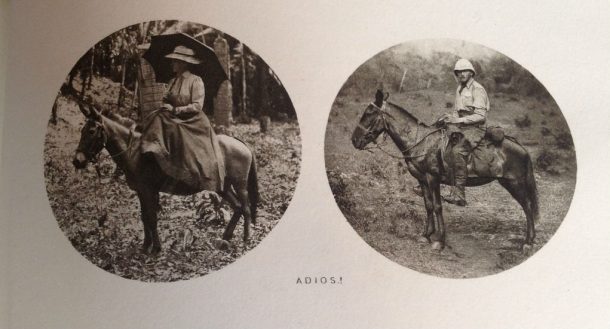

Here is the endpiece, showing them both on their expedition. The book is dedicated to their guide (among others), and Alfred thanks him as follows:

“…my friend Gorgonio, whose gentle manners and sweet disposition helped to smooth over many a bad half-hour during my earlier expeditions, and whose ceaseless vigilance over the welfare of my wife during our last journey did so much to lessen for her the discomforts of camp-life”

Despite some discord between Maudslay and the V&A after the initial gift of the casts and squeezes were not displayed as he expected and were passed on to the British Museum, Alfred Maudslay was still kind enough to bequeath many examples of Mexican and Guatemalan textiles and Mexican ceramics to the V&A, such as this beautiful jar.

Maudslay’s work on Mayan ruins and his collecting and recording of objects laid the foundations for later scholars in attempting to decipher Mayan written language, and his books and casts remain in use by epigraphers today. Although much of his material has been transferred to our colleagues at the British Museum, I was pleased to discover these remaining links with him at the V&A, and to learn more about the history of his collection.

A really lovely insight into Mayan civilisation and more interestingly into the man who brought it to us. My son is starting year 5 and Mayan culture is to be the years topic. We will look forward to enjoying the topic together!