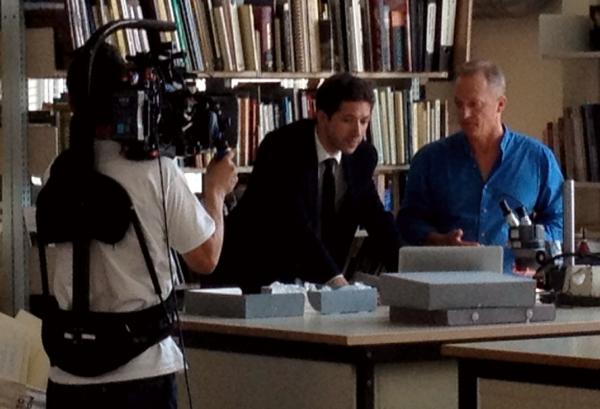

A few weeks ago, the art historian and presenter James Fox (A History of Art in Three Colours, British Masters) came by the conservation department to film a segment for ‘A Very British Rennaissance‘, a new documentary series to be shown next year on BBC 2. He came to discuss the materials and methods used by the great English miniature painter, Nicholas Hilliard with the V&A’s portrait miniatures specialist, Alan Derbyshire.

James Fox and Alan Derbyshire examine a Hilliard portrait miniature under the microscope

According to the BBC, the series will explore the British Renaissance, an epoch that saw Britain shed its medieval shackles and embrace a world of cutting edge art, literature, architecture and science.

James certainly came to the right place to talk about miniatures. The V&A holds the national collection of portrait miniatures – around 2000 objects -and Alan Derbyshire, Head of Paper, Books and Paintings Conservation, has carried out research on the materials and techniques of these exquisite works for more than 20 years. The V&A’s paper conservation studio is also unique in having its own specialist studio specifically for their conservation and examination.

Nicholas Hilliard, ‘Portrait of an Unknown Woman’, 1593. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Miniature painters (or limners) prepared most of their tools and paints themselves. We know that Hilliard in particular was extremely interested in the quality of his materials, and in the purity of his pigments. This knowledge of materials and techniques was passed down from master to apprentice, and is reflected in the fact that Hilliard’s miniatures appear in relatively good condition today. Hillard is also remarkable in his use of three-dimensionality in the application of decorative elements to his works, particularly in the depiction of precious jewels. You can see this in the jewels in the necklace of ‘Portrait of an Unknown Woman’ above, and in detail in his early portrait of Elizabeth I, below. Painted in silver and gold, these jewels appear to shine in the light, and although it may not particularly apparent when looking at his miniatures in their lockets at a distance through glass cases at the museum, it is very obvious when examining his work up close – even more so when one examines this delicate brushwork under a microscope. Hilliard’s skill with a brush in painting at such a small scale is really something to behold.

When trying to understand how limners worked in the 16th and 17th century, we are lucky in many ways that Hilliard wrote his own how-to guide. ‘A Treatise Concerning the Arte of Limning’ was written around 1600, and in it he describes many of the materials and techniques used at that time. However, Hillard’s treatise and others like it do not always tell the whole story, and some of the practical information that might give us clues as to how certain effects were achieved is often omitted. Even after studying the treatise, and carefully examining the often astounding, minute brushwork in a Hillard miniature under a microscope, we are still often left with the question – ‘how did he do that?’.

For example, and as Alan points out to James during their examination of Hilliard’s ‘Portrait of an Unknown Woman’ (above), Hilliard tells us a great deal about the pigments he used, how they were prepared, and the ways in which one should prepare the painted surface, but he was particularly secretive about the painting of his artificial rubies.

Nicholas Hilliard, Detail of jewels from ‘Portrait of Elizabeth I’, c1600. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

One way of rediscovering artists’ technique is through reconstruction. Alan, working with fellow conservator and artist, Timea Tillian, was able to determine how these jewels were created by following original treatises, and physically recreating the effects observed in Hilliard’s miniatures themselves. In the case of the rubies, a tiny circle of shell silver is painted onto the surface of the miniature to supply a reflective surface. Shell silver is made by pulverising silver leaf in honey to reduce it to a fine powder, then adding water and a plant gum binder (like gum Arabic) to create a silver paint that can be applied with a brush. It was pre-prepared for painting and typically kept in an mussel shell, hence its name. After this had dried, a tiny blob of coloured, melted turpentine resin is added using a hot needle (you can see this below on the left). Semi transparent, the resin allows the sheen of the silver to show through, giving it the appearance of a precious jewel. The jewel’s ‘setting’ was typically painted using shell gold (prepared in the same way as shell silver, described above). These tiny areas of gold were then burnished to a high sheen. Everything to do with miniature painting typically being on a very small scale, it was recommended that this was carried out using the tooth of a weasel.

In both of the miniatures above you can see that it is often the case that the silver becomes tarnished over the years, giving the jewels a rather disconcerting black appearance. Below you can see the results of Alan and Timea’s experiments to recreate Hilliard’s famous false rubies.

Recreation of Hillard’s rubies using shell silver, coloured resin and a hot needle. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Understanding how fine art objects were made in an in-depth way requires much more than examination and reading original treatises. As you can see, reconstruction is a method that conservators use to inform their knowledge in a very practical way. But as Alan points out, caution is advised. The practical application of some of Hilliard’s methods, even when closely following his own treatise, also demonstrates that even seemingly simple techniques, such as creating the ruby above, requires extensive research and many practical attempts to even come close to approximating the skills and experience of a professional portrait miniature painter of the time.

You can see James’s interview with Alan on “A Very British Rennaissance”on BBC 2 early next year.