I recently catalogued an unassuming brown leather sketchbook which turned out to contain a wealth of beautiful drawings documenting agricultural work in the British countryside, including haymaking and harvesting. As we’re approaching harvest time I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to share this hidden gem.

The title page of the book is signed simply ‘Lewis’, and the sketches were originally attributed to Frederick Christian Lewis (1779-1856), a British artist known for his engraved reproductions of Old Master drawings. However, Frederick came from a family of artists, and the Royal Academy suggests that the sketchbook may in fact have belonged to his brother George Robert (1782-1871), while admitting that ‘the process of determining authorship is complicated by Lewis’s prodigiously artistic family environment.’ The whole Lewis family spent summers on a farm in Kempston Hardwick, Bedfordshire, developing their drawing skills through observing landscapes, animals and agricultural scenes. George also spent the summer of 1815 in the fields at Haywood, Herefordshire, and the following year he exhibited twelve paintings of haymaking at the Society of Painters in Oil and Water Colours, four of which are now in the Tate collection. In the early 19th century there was a movement towards naturalism and authenticity in landscape art, embraced by artists such as John Constable, John Linnell and Peter De Wint, and all of Lewis’ Haywood paintings include the words ‘painted on the spot’ and note the location and time of day. The sketchbook, too, shows a keen observation of movement and attention to detail that could only have been done on the spot.

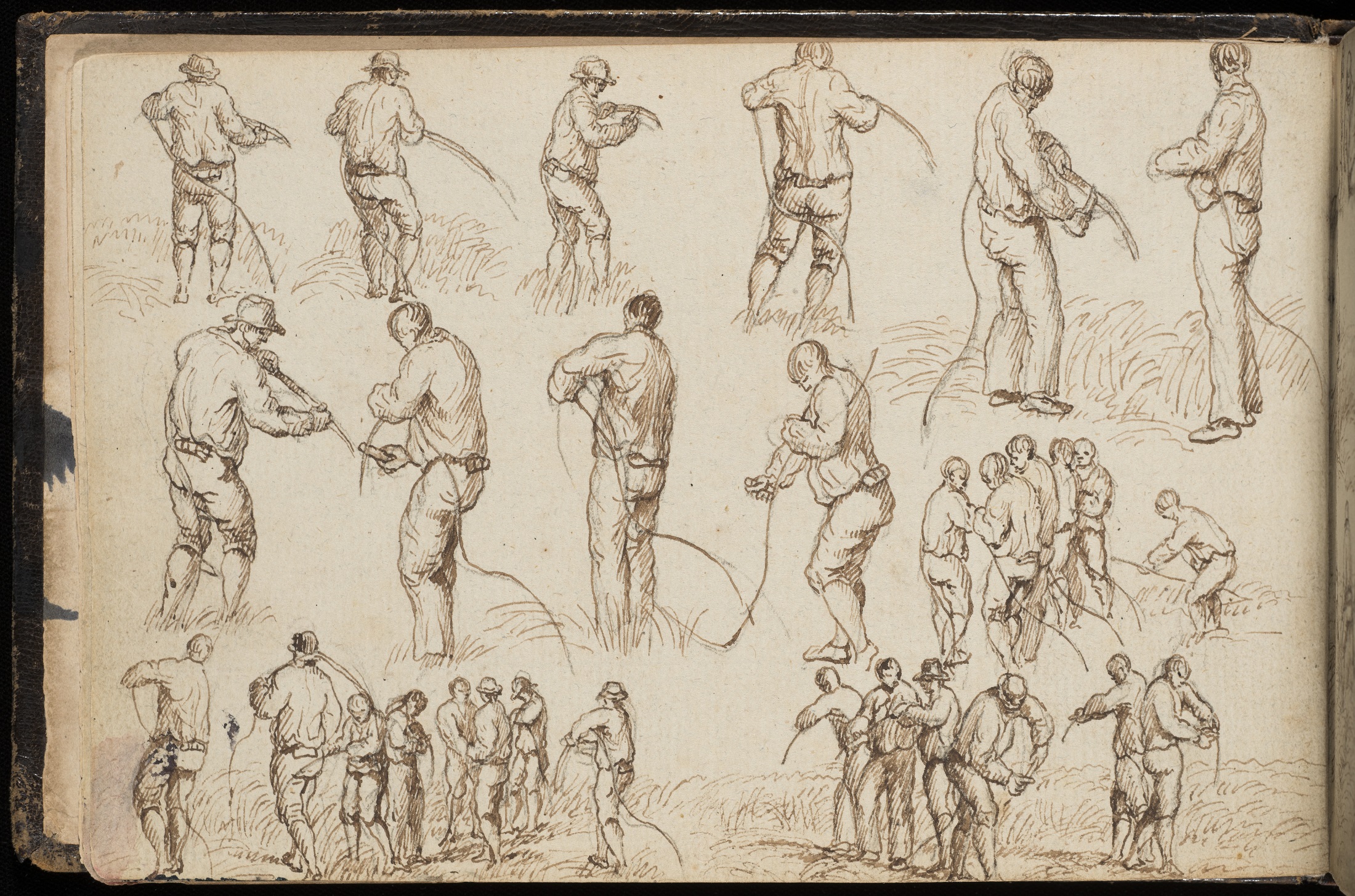

The book contains depictions of each stage in the process of haymaking – a vital part of the farming calendar, providing food for the animals during the lean winter months. The first stage is mowing the grass, which in the 19th century was done by hand using a scythe, as seen in the below sketches. Each page of the sketchbook starts with rough pencil drawings, capturing the range of movement and different body positions of agricultural labourers at work. Lewis later added to many of his sketches, adding detail with pen and ink, tone with wash, and in one case creating a full colour scene with watercolours.

The worked-up sketches and particularly the finished paintings made for sale sacrifice to some extent realism for romanticism, playing down the poor conditions and poverty among rural workers, and emphasising the more pleasant aspects, such as the sense of community and beautiful location. However, the number of sketches from different angles shows Lewis’ commitment to capturing the physicality of the labourers, and the hard work involved in these tasks.

In this pen and ink sketch workers use whetstones to sharpen their scythe blades. Blades needed to be resharpened frequently during mowing to keep the scythe gliding smoothly through the grass, and many workers carried a whetstone in a holder attached to their belt.

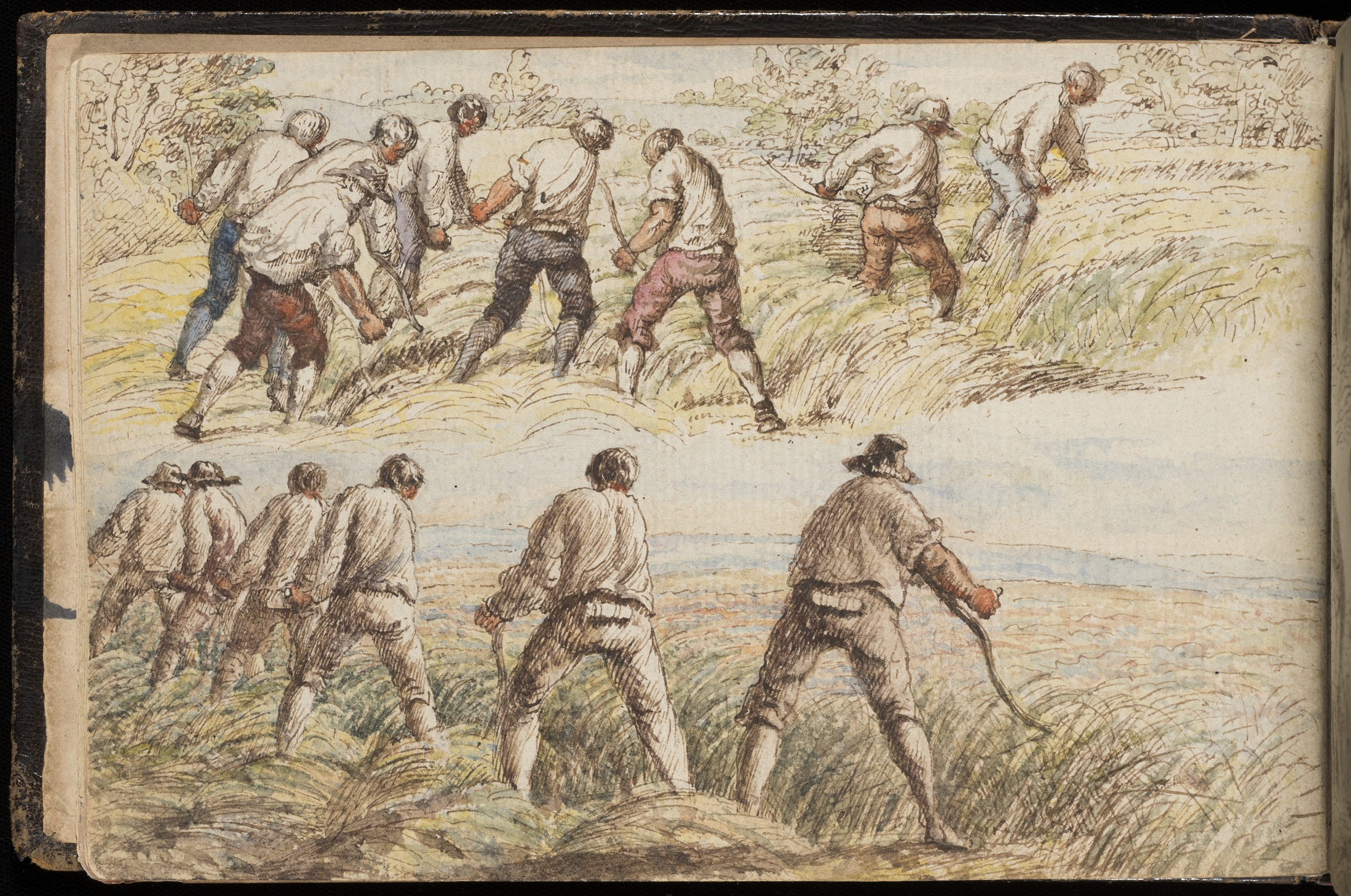

Scythes sharpened, the men would line up in rows to work their way along the field, each staying at a safe distance from their neighbour’s swinging blade. The scythe had changed little in design since it was first introduced to Europe in the 12th century, and consisted of a wooden shaft (known as a snaith or snath) with a handle in the middle and a long, curved steel blade. The blade was held parallel and close to the ground, and the mower swung it in an arc, slicing the grass before moving forward to the next patch.

Only men were involved in mowing, but women participated in many of the tasks that followed. Here, under the shade of a large tree, we see both men and women raking and turning the grass, making it into rows (windrows) or piles (haycocks) to dry out into hay. Haymaking was apparently popular among the better-off who wished to get a taste of farming life – the poet and essayist Leigh Hunt suggested that ‘ladies may practice haymaking on a small scale upon lawns and paddocks; and if they are not afraid of giving their fair skins a still finer tinge of the sunny, nothing makes them look better’. (Leigh Hunt, The Months, London: 1821, p.72)

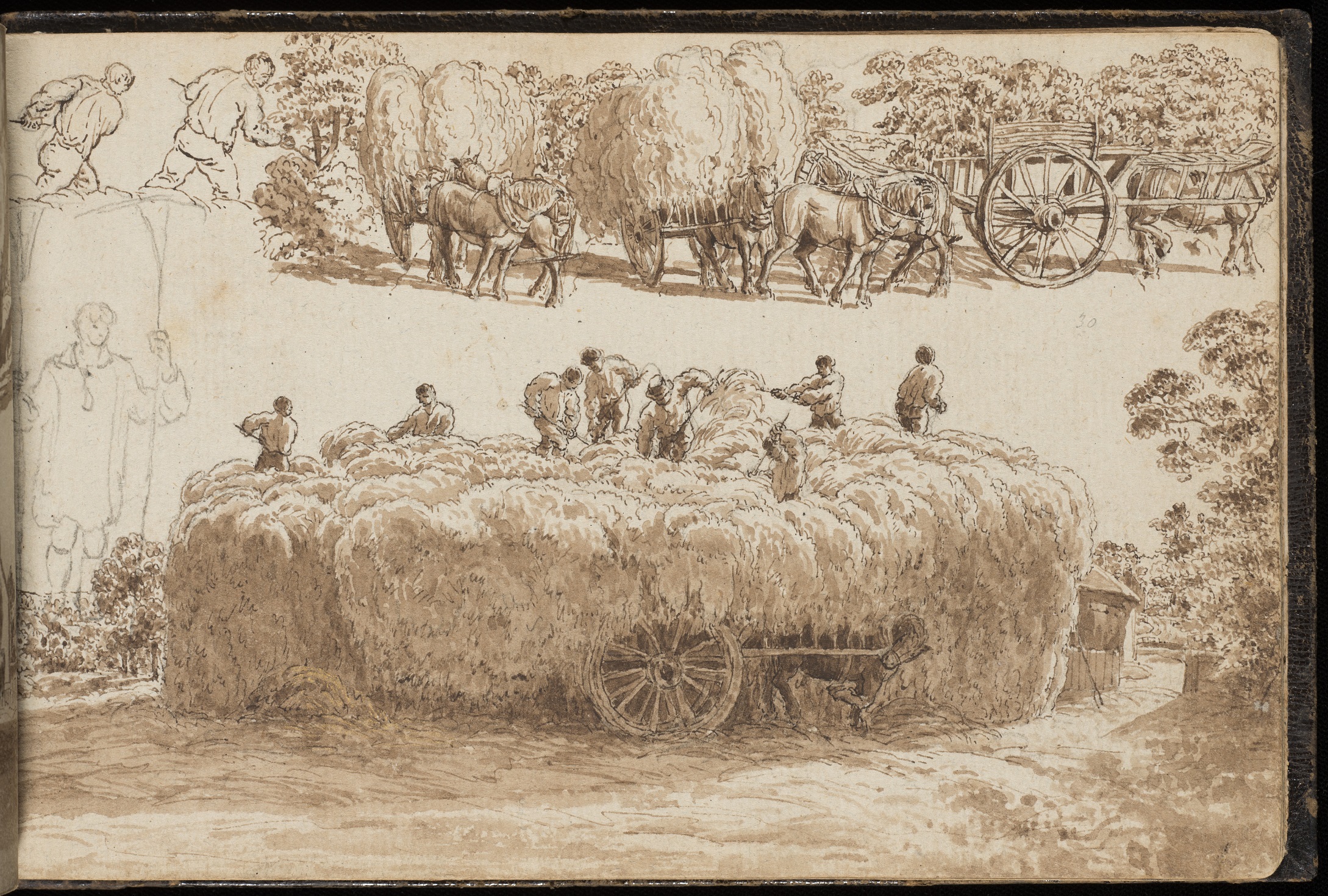

Once the hay had dried out it was loaded onto carts using pitchforks – later, machines packaged it into bales but in these drawings it is loose. This page of the sketchbook is typical in depicting a more fully realised scene with smaller studies around it, including a tiny image of a cart and horses in the bottom left.

The loaded cart was a popular motif in rural scenes of this time, signifying prosperity and plenty. I am slightly concerned about the strain being put on the poor horse under this cart!

Back at the farm, the hay was pitchforked from the cart to form a hayrick – a large, almost house-shaped structure from which slices could be cut when needed to feed livestock and horses. A badly-timed rainstorm could spell disaster for the crop, so this rick appears to have a canopy that can be unfurled to protect it.

Hard physical labour and hot summer days made rest breaks a necessity, and these scenes of relaxation are common in rural art. They emphasise the sense of community and the pleasures of rural life, and women and children were often included in these scenes to add to this impression. I love how the different tones of wash and the use of white space captures the brightness of the sunny day and the shadows inside the barn.

The sketchbook focuses on haymaking, but there are also some images of wheat harvesting, which involved different tools and techniques. The drawing below shows several different stages, including reaping the wheat with a sickle, gathering it into a bundle and tying it into sheaves with straw rope The sheaves were then bound together as stooks or shocks (which can be seen in Lewis’ ‘Harvest Scene’ in the Tate). Any stalks or ears left behind were ‘gleaned’ or gathered by the poor, usually women and children.

This sketchbook is a beautifully detailed and well-observed record of a summer spent in the English countryside, bringing us closer both to the artist and to a vanished way of life. If you would like to see this or other sketchbooks up close, please do visit the Prints and Drawings Study Room – full information can be found at https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/study-rooms#prints-drawings-study-room.

Acknowledgement: Christiana Payne’s book Toil and Plenty: Images of the Agricultural Landscape in England 1780-1890 (Yale, 1993) has been a great help in writing this post, and is a fascinating read for anyone interested in learning more about the topic of agriculture in art.