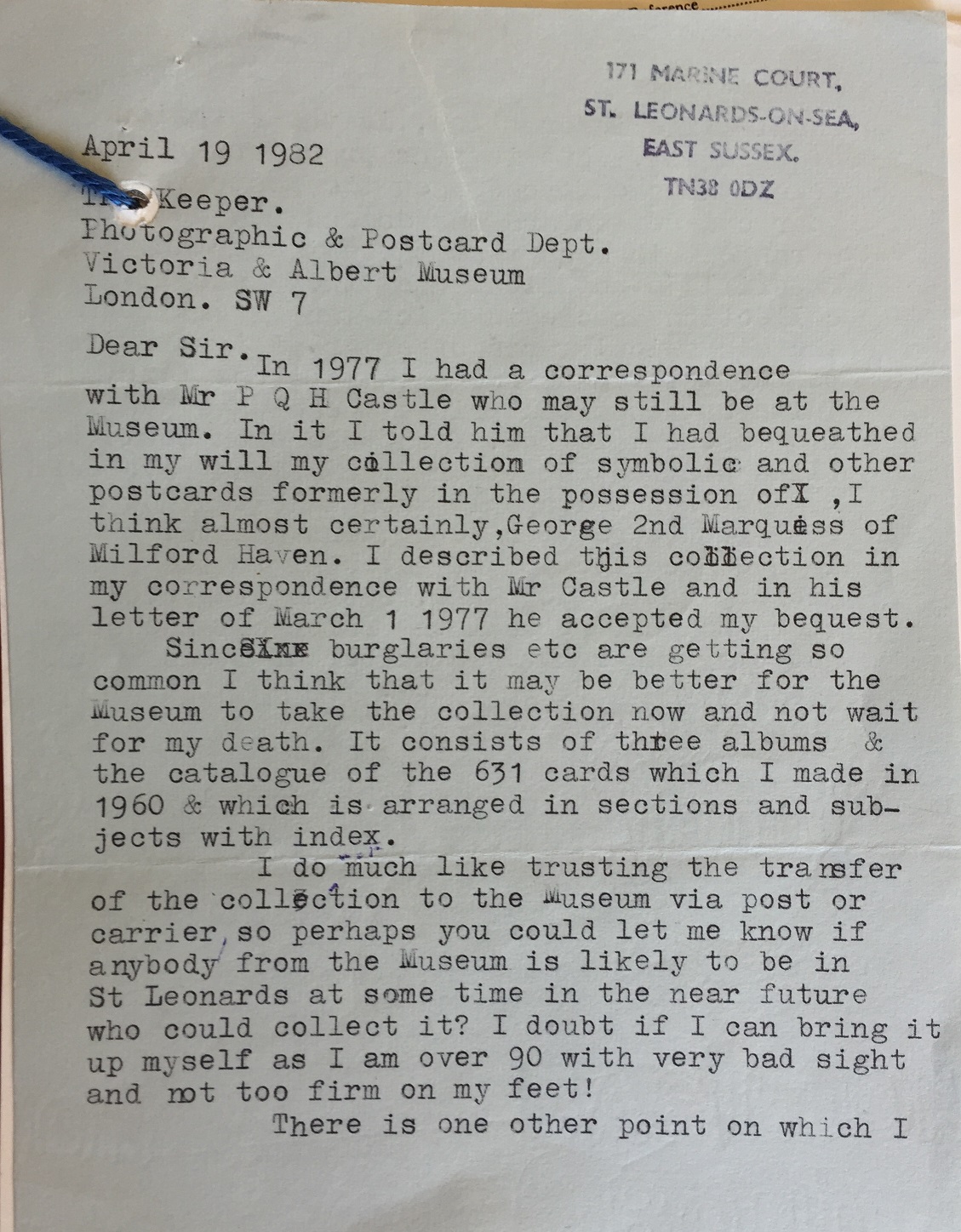

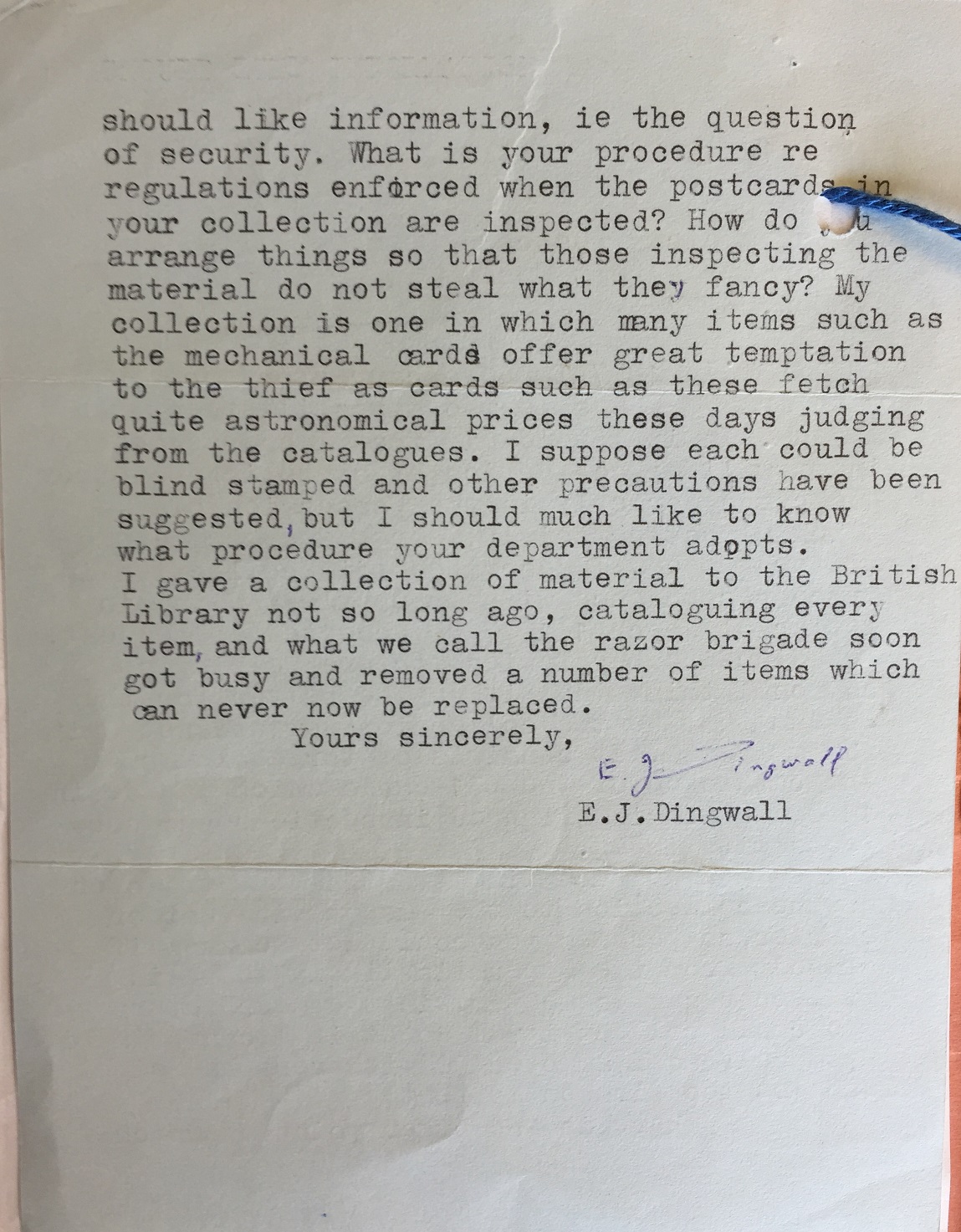

In April 1982, a typewritten letter from E.J. Dingwall (1891?-1986) of St. Leonards-on-Sea addressed to the ‘The Keeper’ of the ‘Photographic & Postcard Dept.’ was forwarded to the Curator of Photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Dingwall was following up on his 1977 correspondence with Peter Castle, Senior Researcher in the Library at the Museum, concerning a collection of over 600 postcards Dingwall described as ‘symbolic’ and ‘formerly in the possession of, I think almost certainly, George 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven’. According to Dingwall, Castle had accepted on behalf of the V&A his bequest of this collection. Five years later, Dingwall, 90+ years of age and citing a rise in burglaries, was anxious to transfer the collection to the V&A immediately, rather than upon his death.

Letter from E.J. Dingwall to Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A Archive, Nominal File: MA/1/D1182

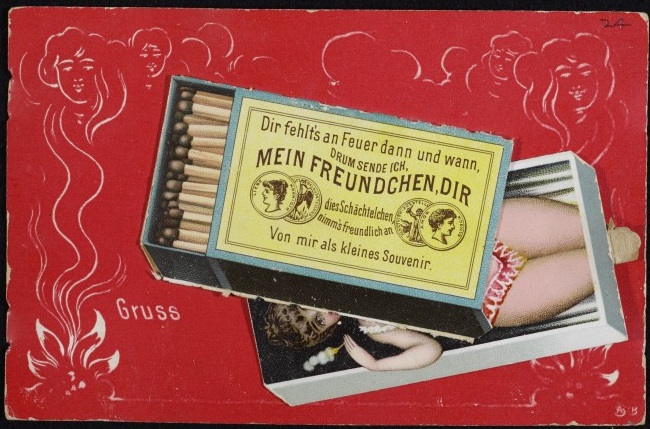

The postcards are more accurately described as ‘erotic postcards’. They feature examples of both photographic and illustrated imagery of nudes, sexual activity and sexual symbolism. These types of cards, often referred to collectively as ‘French Postcards‘ despite production throughout Europe, were very popular during the late 19th century through the early 20th century. The specific collection offered by Dingwall featured objects dating from about 1900 to 1916 and included examples from France, German and Italy.

Photograph, postcard, French, c. 1910

E.523:87-2001

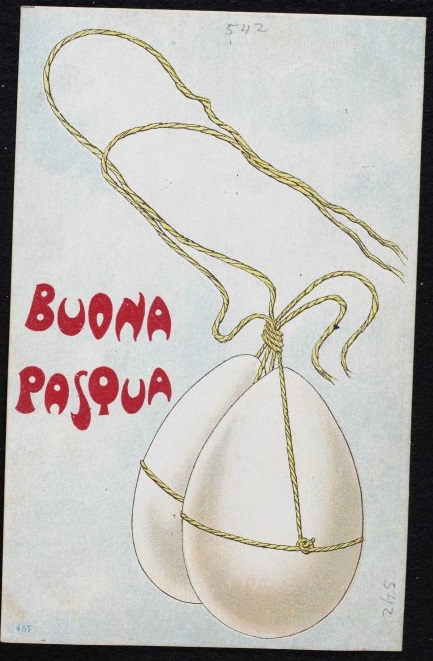

Postcard, lithograph, Italian, c. 1905

E.525:542-2001

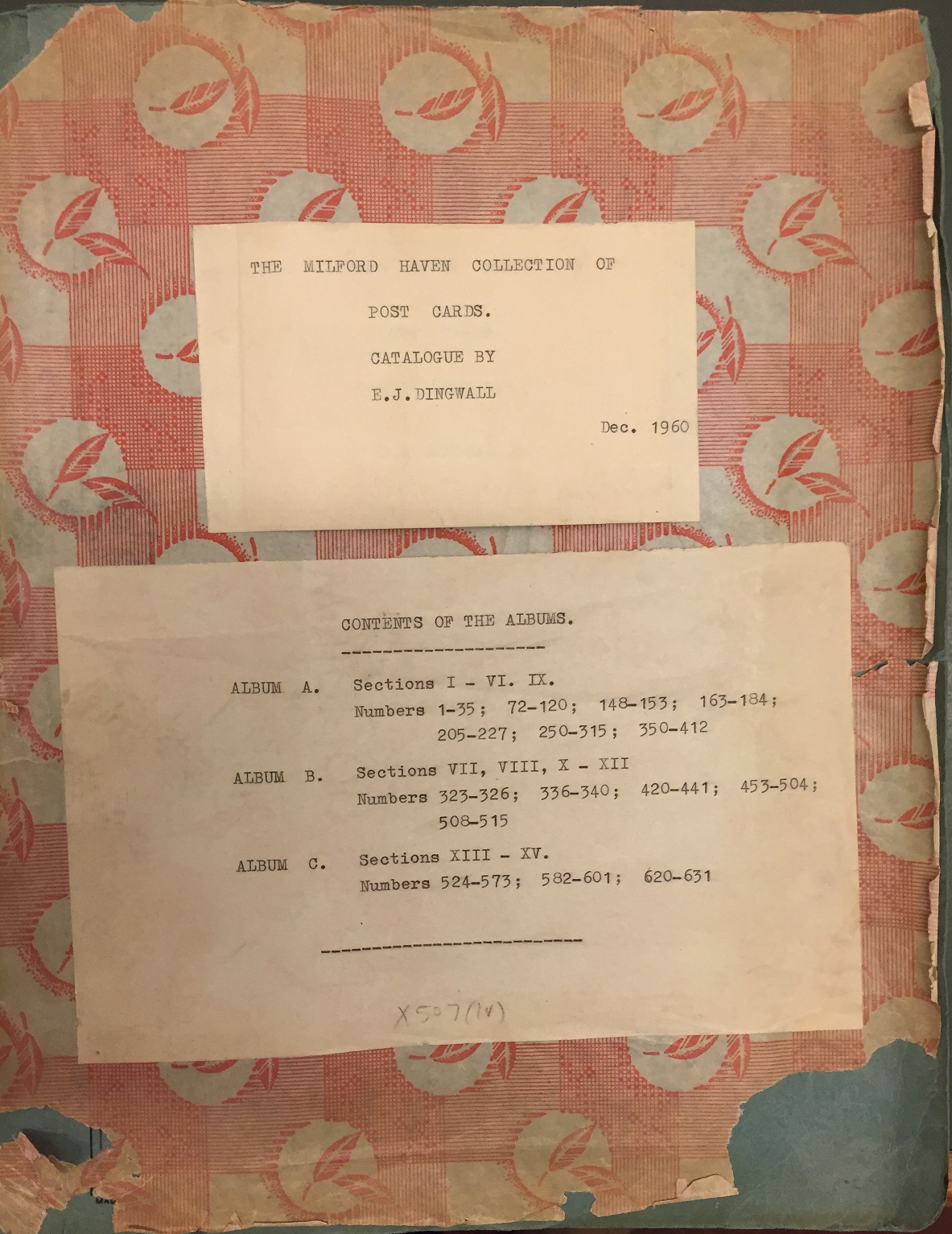

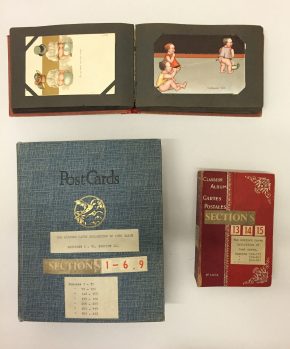

Accompanying catalogue prepared by E.J. Dingwall

The V&A’s archives show an unsuccessful attempt within the Museum to track down the original correspondence to which Dingwall referred. Further inter-department notes include ambivalence about the gift and the curator’s admission to colleagues that ‘I suppose we [the V&A] are committed to accepting this gift.’ Consequently, on May 7th 1982, C.M. Kauffmann, Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings & Photographs replied to Dingwall with thanks and plans to arrange for the transport of the collection.

As Dingwall was also gifting to the Museum a pair of Chinese ceramic boxes, a curator in the Far Eastern Department was despatched to collect the postcards along with the ceramics. They arrived at the Museum in three bound albums accompanied by a detailed typed catalogue prepared by Dingwall. Kaufmann promptly acknowledged their safe arrival to Dingwall, reassuring him about the invigilation safeguards in place at the V&A.

Perhaps the initial lack of enthusiasm for the gift explains the delay in appropriating resources to the collection and accounts for the fact that it was not until 2001 that the cards were actually catalogued and given museum numbers. But recently, as part of a long-term and ongoing project to digitize the whole of the V&A’s collection, this quirky collection was identified as one which would benefit from further research and documentation.

The postcards themselves are interesting, and include some rare examples of moveable cards (known as cartes articulées), But the story of Dingwall and this collection is equally fascinating.

Information concerning Dingwall has recently been made available to the public as a result of Wellcome Trust funding to catalogue his archive, held at the Senate House Library of the University of London. Dingwall was probably best known as a psychical researcher. He investigated many curious cases and had a deep interest in paranormal phenomena. He wrote extensively on the topic, including the 1927 How to go to a medium: a manual of instruction. While Dingwall believed in the validity of the paranormal phenomena, he was also critical. As a member of the Society for Psychical Research, Dingwall was instrumental in exposing as fraudulent the Crewe Circle, a spiritualist photography group founded in the 19th century.

Later in life, Dingwall expanded his study to that of ‘strange and queer customs’, and began to pursue his other main interest, the study of human sexual practices and erotic literature and ephemera in all languages. Along the way he published his findings in articles and books with titles such as: The Girdle of Chastity (1931); The American Woman: An Historical Study (1956); Very Peculiar People: Portrait Studies in the Queer, the Abnormal and the Uncanny (1950).

Very Peculiar People, 1950

His specialization in erotica resulted in his appointment at the British Museum as Honorary Assistant Keeper in the Department of Printed Books with special oversight of the Museum’s ‘Private Case’ of obscene literature. According to Christopher Josiffe, a cataloguer at the Senate House Library, Dingwall’s research into this topic had him variously known as the ‘British Kinsey’, the ‘pornographer royal’ and ‘Dirty Ding’.[i]

Dingwall’s representation of the material as the former property of George, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven, (otherwise known as Sir George Mountbatten, 1892-1938), was not unlikely. Josiffe, citing a 1991 history of the Library of the British Museum, writes that the 3rd Marquess (David Mountbatten) offered a collection of pornography to the Library at the British Museum in the early 1960s.[ii]

The timing coincided with the police investigation into friends and associates of osteopath Stephen Ward, (one of the central figures in the Profumo Affair, the 1960s British political scandal, and a friend of Mountbatten’s). The investigation threatened to expose Mountbatten’s extensive pornography collection and as a close friend of Prince Philip, such exposure might cause embarrassment to the Royal Family.

According to Josiffe, the erotic material ended up in the Library’s ‘Private Case’, presumably in an arrangement ‘brokered by Dingwall’, with the rejected items going to the Kinsey Institute for sexual health research. [iii]

If this is true, it seems that not ALL of the Milford Haven material found its way to the British Museum’s ‘Private Case’ or the Kinsey Institute. The Milford Haven Collection of postcards somehow ended up with Dingwall and was subsequently gifted to the V&A. The specific circumstances and terms of Dingwall’s acquisition of the postcards remains unknown.

The collection arrived at the Museum meticulously catalogued by Dingwall. It was divided into 15 specific categories, each defined by tabs and a complicated numbering system. They were: I: General; II: Nudes; III: Prostitution; IV: Underclothes; V: Seduction; VI: Sexual Activity; VII: Breasts; VIII: Tongue; IX: The Buttocks; X: Defecation; XI: Urination; XII: Phallic Scenes; XIII: Symbolism; XIV: Animals in Symbolism; XV: Changing Cards. The accompanying catalogue contained individual typed entries for each card with a brief description of the depicted scene, translations into English of any printed text, and where possible, explanation of the meaning of illustrated double entrendres, puns, etc. There are also commentaries on the significance and history of some of the illustrated themes.

Dingwall presented the material in a manner consistent with his reputation as a fastidious archivist, reliant upon scientific rigour. For example, under the catalogue entry for Section XII: Symbolism, Dingwall writes: ‘From the psychoanalytical point of view the cards are of especial interest since they show many of the Freudian symbols which were perfectly understood by ordinary people some time before psychoanalytic theories regarding dream interpretation and the meaning of many symbols were being discussed outside medical and psychological circles..’ Or Section IX: The Buttocks: ‘The collection is well representative of these [scatological] examples of crude humour and the different treatment of the same theme by French, German and Italian artists is especially to be noted.’

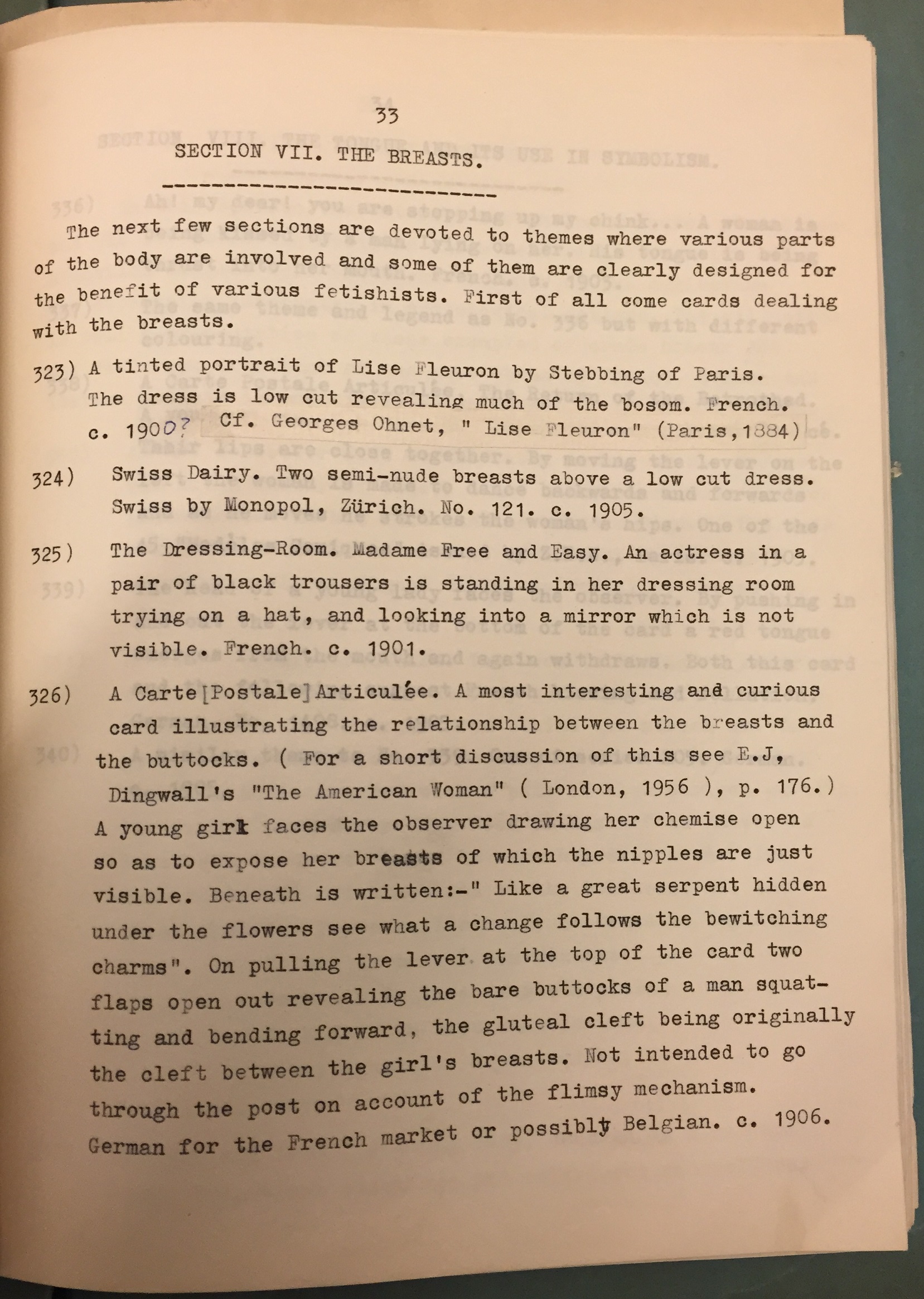

The collection includes examples by some of the most prolific erotic postcard illustrators of the period including Xavier Sager and Georges Mouton.

Postcard, lithograph by Georges Mouton, French, c. 1904

E.524:427-2001

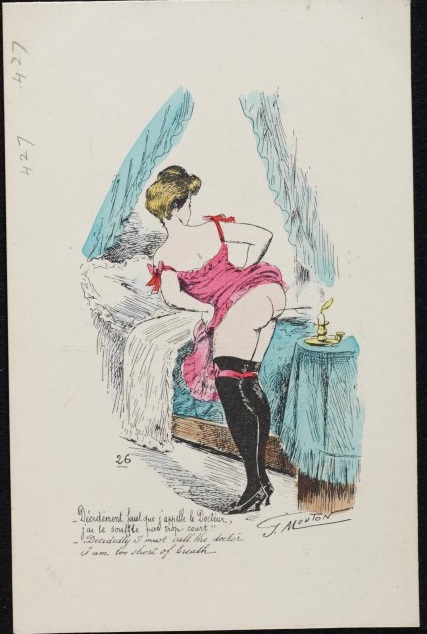

Postcard by Xavier Sager, lineblock print, French, c. 1903

E.523:409-2001

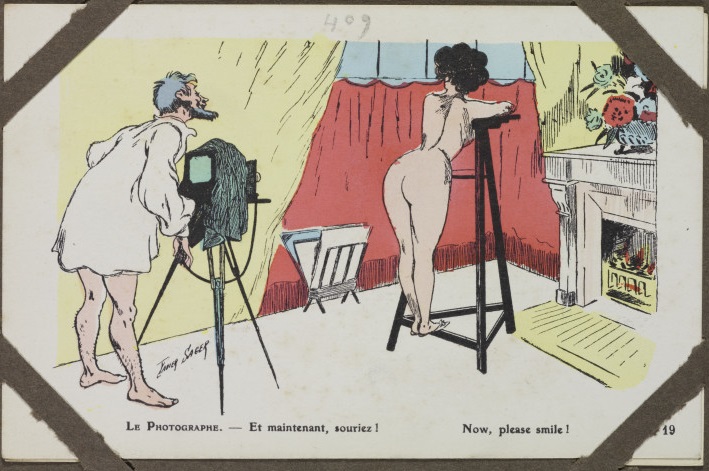

The moveable cards are particularly interesting and rare.

Moveable postcard, lithograph, German, 1906

E.523:24-2001

And there is a series of cards that are designed to be viewed through a red transparent screen in order to see the erotically charged illustration.

The cards themselves are in excellent condition and tell us much about the history of pornography, the original collector, but also much about Dingwall himself.

[i] Christopher Josiffe, ‘’Dr. Dingwall’s Casebook, A Sceptical Enquirer, Part Two: ‘Dirty Ding’” in The Fortean Times, May 2013, no. 300: p.50-54.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

Fascinating stuff. His comments on Freudian imagery are particularly interesting. Where the connection is serious, it’s not so arcane as some would have it.