In researching the work and career of Isabel Agnes Cowper (1868 – 1891), the V&A’s first female Official Museum Photographer, one photograph has always stuck out to me as an anomaly. In a career focused on the recording of Museum objects, this photograph, a still life composition, is, to date, the only ‘artistic’ photograph by Cowper identified among the known inventory of her work, a collection that numbers in the thousands.

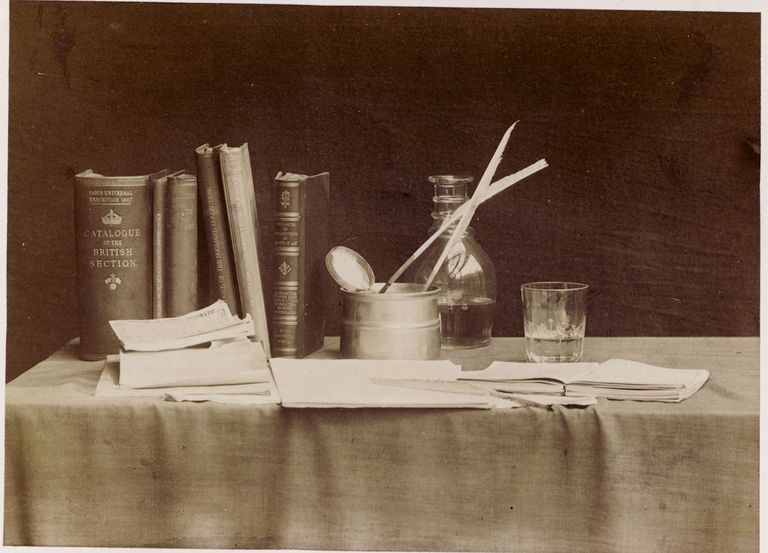

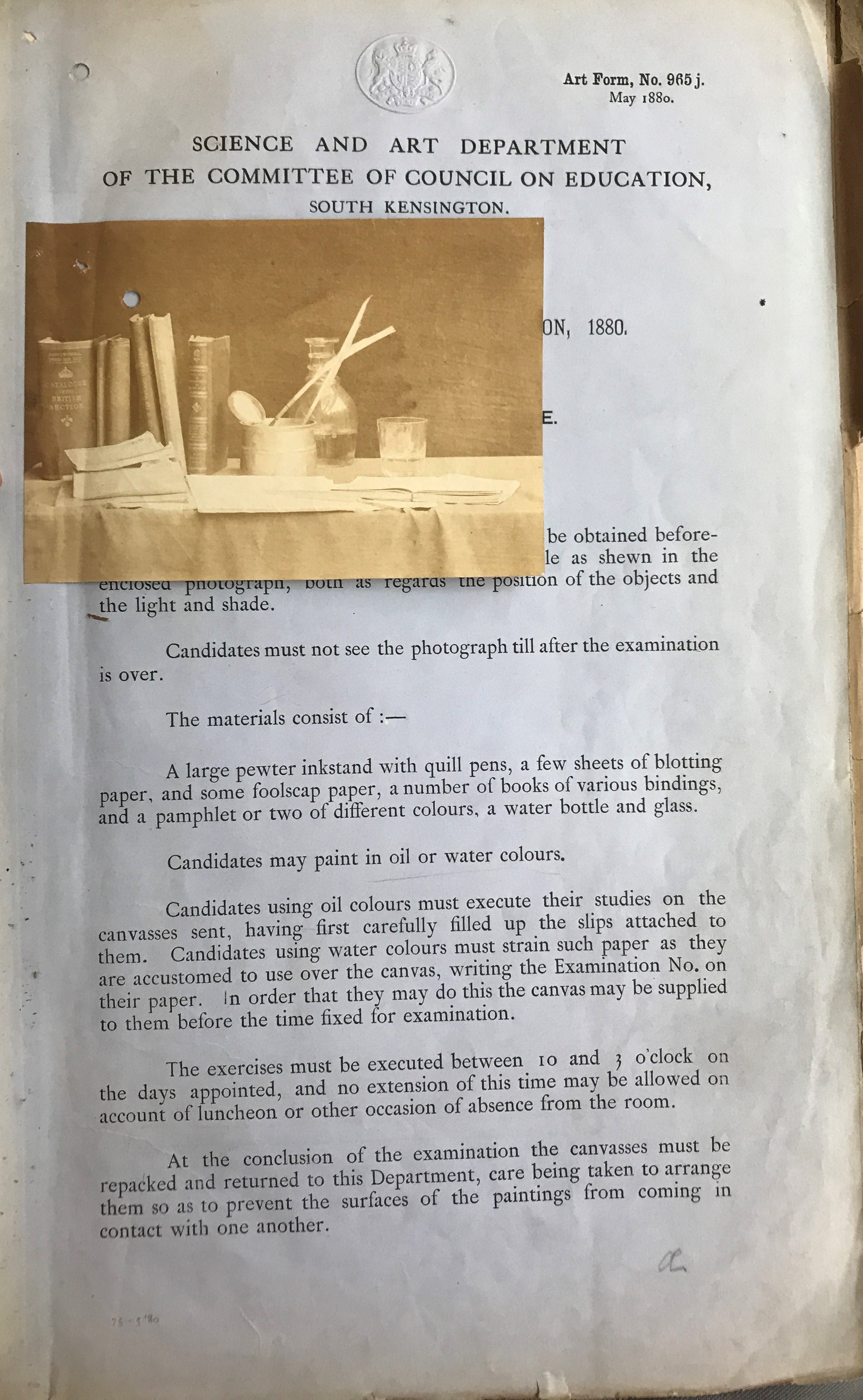

This artfully staged composition, an albumen print, includes a quill pen and inkpot, exhibition and museum catalogues, foolscap paper and supplier’s brochures. The view is enlivened by a tumbler and carafe, in which the Museum’s daylight studio is reflected.

Even before the current research into Cowper’s career began, the photograph struck a chord with V&A curators, who included it in the 2002 exhibition Seeing Things: Photographing Objects, 1850-2001. Cowper’s still life was installed in the gallery and reproduced in the exhibition catalogue among an ‘all star’ line-up that included Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Diane Arbus.

The still life is listed in the original photographs register as having been received in 1880 ‘from Stores (Mrs Cowper)’. Cowper took on the role of Official Museum Photographer in 1868 upon the death of her brother, Charles Thurston Thompson, the first Official Museum Photographer of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). Thurston Thompson was installed in the role in 1853 by Henry Cole, the V&A’s visionary founding director, who saw early on the potential of photography to dramatically extend the visual resources of the Museum available to artists, students and the public. Cole conceived of a forward-thinking photography policy that included in-house photography documenting museum objects and temporary exhibitions.

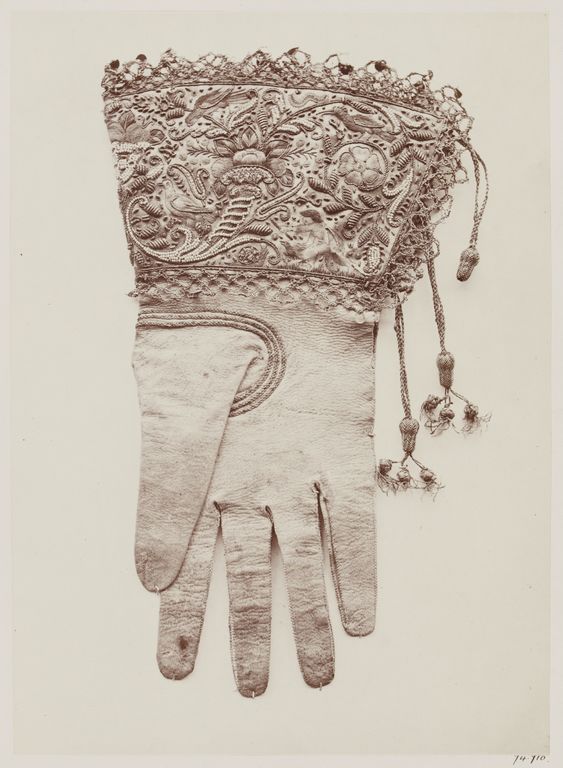

As Official Museum Photographer (possibly the first woman to be employed in that role), Cowper was primarily tasked with supporting this policy, recording Museum objects, including objects on loan and installation views of exhibitions. She excelled at documenting art objects against a plain background without any contextualizing information, a format that Svetlana Alpers has dubbed ‘the museum effect’. This mode of expression served to maximize the utility of the reproduction, making it suitable for a diverse range of consumers and uses. As part of this undertaking, she also supplied of photographs to be used in books published by the Museum. These books were part of a nascent publishing project illustrating loan and Museum collections in photographically illustrated books.

These photographs and books were collected in the National Art Library where they available for consultation by artists and scholars. Other copies were circulated to National Art Training Schools, distributed as prizes to students of merit, sold to the public in a dedicated on-site sales room and used by Museum personal in support of a range of curatorial activities.

At first glance, the composition of this still life is remarkable in the ways in which it defines Cowper’s role as Official Photographer, which likely involved record keeping in quill pen and ink, the production of catalogues and the perusal of suppliers’ brochures. The reflection of the daylight studio reveals details about Cowper’s working methods. In the early 1880s, she would have had to prepare her negatives, coating glass plates with a collodion solution. Once focus was achieved, while still sticky with solution, the plate would be inserted into the camera and exposed – a process dependent upon an abundant and steady supply of natural light. The reflection of the studio showing large skylights, confirms Cowper’s reliance upon this daylight.

The catalogues and books Cowper chose for the composition provides another clue to details of Cowper’s professional life. Of the six volumes, five of them represent or refer to Cowper’s work as Official Photographer. A search of the original photographs register reveals that two of these books, including the Guide to the Duke of Edinburgh’s Collection (1872) and the Catalogue of Objects of Indian Art (1874) are illustrated exclusively with photographs made by Cowper or with wood-engravings based upon her photographs. The 1869 Catalogue of Reproductions of Works of Art: Electrotypes, Plaster Casts, Fictile Ivories, Chromolithos, Etchings, Photographs (1869) listing museum reproductions include those made by Cowper (though unattributed). The photographs included in Italian Sculpture of the Middle Ages (1869) were printed from Charles Thurston Thompson’s negatives but registered as having been received from Mrs Cowper, who oversaw the stores of his negatives after his death. The Paris International Exhibition: Catalogue of the British Section (1867) is also significant as it recalls Cowper’s first appearance as part of the photographic service of the Museum. This is corroborated by Cole’s 6 November 1867 diary entry referencing Thurston Thompson’s arrival at the Paris Exhibition on official museum business with ‘Mrs. Cowper’. But this begs the question, did Cowper randomly assemble this still life from the clutter on her desk? Or did she consciously choose a majority of volumes that would illustrate the large quantity and broad reach of her work?

Looking beyond the subject matter, the singularity of this constructed photograph in the context of Cowper’s career as a maker of documents, poses questions relating to its original purpose and use within the Museum. To explain the inconsistency, I initially posited that it might represent a surviving example of a ‘practice shot’ by Cowper, part of a program of self-directed professional development. But as this photograph dates to 1880, twelve years after Cowper was first employed, I discarded this supposition as Cowper would have been a seasoned professional by this point.

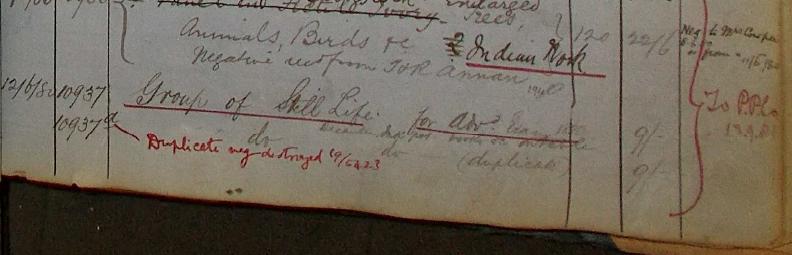

Diving deeper into the archive, I consulted the 19th-century Negative Register, a hand-written record of every negative produced by Museum photographers, each assigned a sequential number as they were received into the Museum. This channel of enquiry provides a tantalizing clue. Negative number 10937, titled ‘Group for Still Life’ is annotated in faint pencil: ‘for Adv. Exam 1880 / decanter, ink pots, books, etc. on table’. Cowper was paid 9 shillings for the negative on 12 June 1880. While this reveals interesting facts about women’s work and compensation within museums in the 19th century, also significant is the reference to advanced examinations.

The South Kensington Museum was only one division administered by the Department of Science and Art, which also oversaw a network of national art training schools. As part of the schools national curriculum, students sat exams in topics deemed essential to demonstrating competency in art and design.

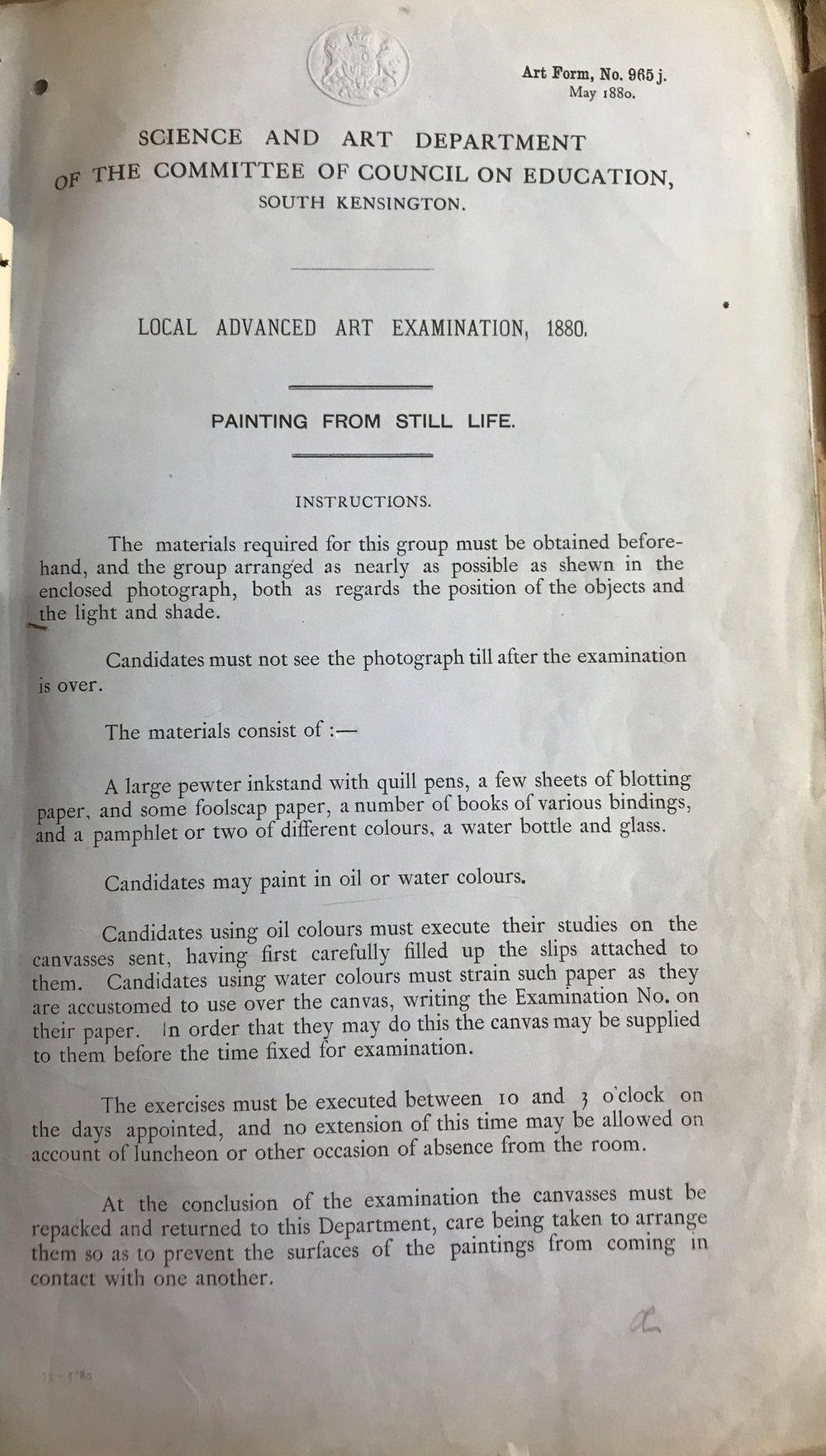

Following this thread, I consulted the original examination papers for 1880 residing within the V&A Archive. Included among the examination documents was the original test paper defining the conditions and terms for the execution of a still life in either oil or water colours.

This paper would have served as guidelines to the local instructors administrating the examination. Note the top requirement:

The materials required for this group must be obtained beforehand, and the group arranged as nearly as possible as shown in the enclosed photograph, both as regards the position of the objects and the light and shade.

The guidelines go on to define the preparation of the permissible materials and the timeframe allowed for the exercise, noting that ‘no extension of this time may be allowed on account of luncheon or other occasion of absence from the room’.

And then – found bound with the examination was another copy of Cowper’s still life, the same still life featured in the V&A’s 2002 exhibition. This was the photograph referenced in the guidelines. Its inclusion with the examination paper indicates that it was distributed along with the examination guidelines to regional schools to be used as a template for the local instructors administering the exams.

According to the official Report on the National Competition of the Works of Schools of Art, 1880, the competition ‘showed a general extension of sound methods of painting. No single work was characterised by such completeness or sense of perfection as to give entire satisfaction; and the award of four Silver medals, but no gold Medal, marked the Examiners’ opinion of the degree of success attained. The paintings had generally lost freshness through being overworked, from want of a sufficiently direct method of execution.’

A survey of exam papers from the years surrounding 1880 reveals that, beginning in 1879, the Department of Science and Art regularly engaged photography as a tool to provide templates for the still-life exam to regional schools. This might be the first example of photography employed in the institutional assessment of art students. It’s a method that would guard against accusations of regional bias, ensuring that students were working from comparable examples no matter where the exams were sat.

Up until the discovery of the duplicate copy of this image attached to the 1880 examination paper, this staged photograph was a source of curiosity for scholars of Cowper’s career. But now, examined from different angles, it reveals the multiplicity, and dynamic nature, of the ‘work’ that photographs can do, even when regarded within the confines of a singular institution. In this brief analysis, the subject matter lets slip details of Cowper’s professional life; a clue concerning the circumstances of production illustrates the ways in which photographs were used throughout the Museum; and more recently, Cowper’s inclusion in an exhibition that argues for the art status of photography, identifies her as an artist with a keen eye for composition.