Did you know that the V&A was the first museum in the world to use gaslight in its galleries? This innovation was the brainchild of Henry Cole (1818-1882), the V&A’s first Director, who believed that extending the Museum’s opening hours until 10pm on two evenings a week would further his social reformist agenda by enabling working class people to visit after work and so ‘furnish a powerful antidote to the gin palace’, as he memorably put it.

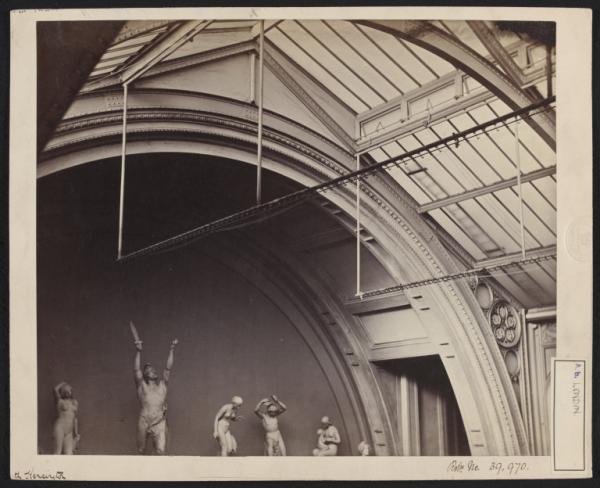

North-east corner of the South Court showing statuary on balcony (Gallery 102) and gaslight fixtures, c. 1862. V&A Archive, MA/32/15 Guardbook neg. 3022. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As if to underline the importance of this new lighting technology, Queen Victoria’s first visit to the Museum took place at 9.30pm. The Morning Post reported that she was ‘particularly pleased with the manner in which the gallery of paintings was lighted’; following technical rehearsals 4 days before the Queen’s visit, Cole recorded in his diary: ‘Sheepshanks room tried & quite successful’.

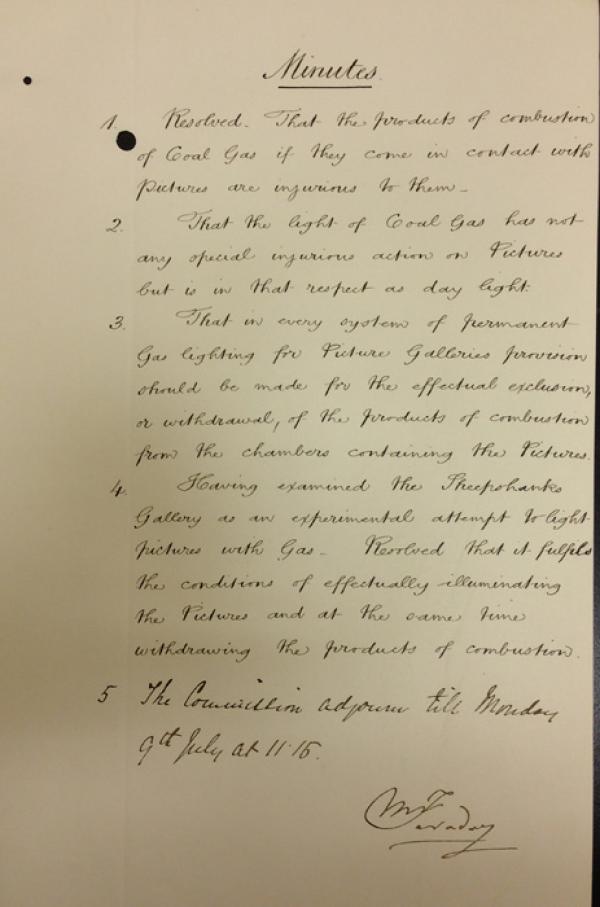

Subsequent concerns about the potential polluting effect of gas effluvia on paintings were allayed by a scientific commission chaired by the distinguished chemist Michael Faraday (1791-1867) which reported in 1859 that under suitably controlled conditions there ‘is nothing innate in coal gas which renders its application to the illumination of picture galleries objectionable’.

Minutes of the Commission to consider the subject of lighting picture galleries by gas, signed by Michael Faraday. V&A Archive, ED 84/60. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

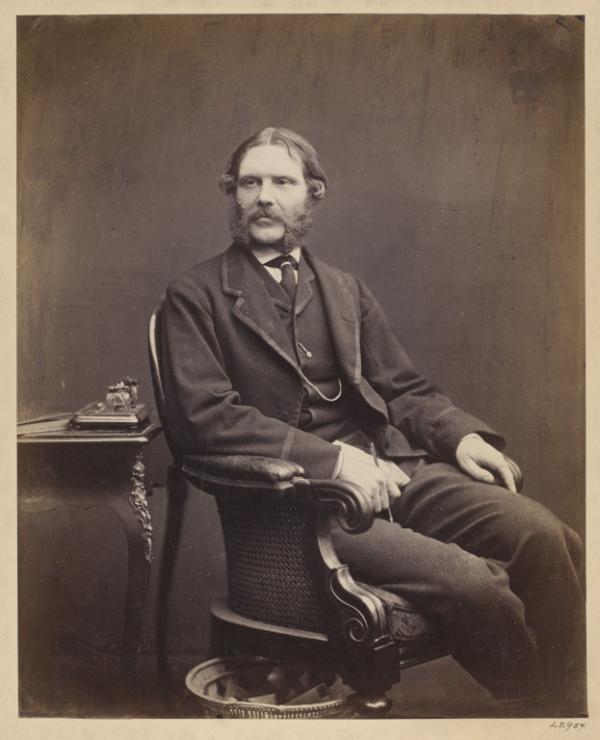

The Sheepshanks Gallery was the first of the V&A’s public spaces to use gaslight. John Sheepshanks (1787–1863), who had presented to the nation his significant collection of paintings and drawings by contemporary British artists in 1857, stipulated that his gift be displayed in a purpose-built (‘well-lighted and otherwise suitable’) gallery. Designed by the architect and engineer Captain Francis Fowke (1823-1865), the gallery opened on 22 June 1857 and was lauded by the press as ‘the first public gallery ever perfectly lighted by day and gas light’.

Photograph by John & Charles Watkins, ‘Portrait of Captain F. Fowke’, albumen print, ca. 1860. Museum no. 48:957. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

During the day, natural light entered the gallery through ‘an aperture 10 feet wide along the roof, glazed externally with clear glass, a second glazing of ground glass being placed below’. A holland blind, fitted between the two skylights, could be drawn if necessary to block out the sun.

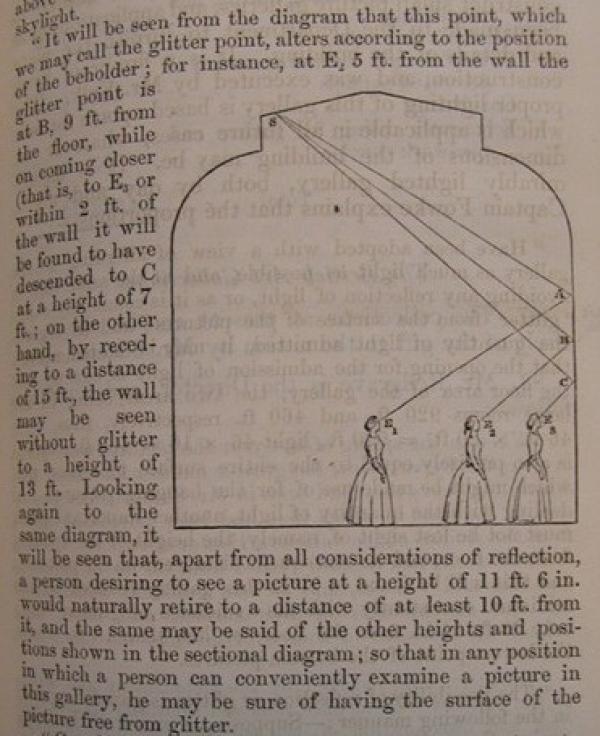

Fowke based his glazing scheme on a formula calculated to reduce or eliminate the ‘possibility of reflection or glitter’ from natural light on the surface of the paintings.

Diagram showing how the ‘glitter point’ varies according to the position of the visitor. Fifth Report of the Science and Art Department (London: HMSO, 1858). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

At night, the gallery was illuminated by gaslight: 112 burners in the two large rooms, 84 in the two smaller rooms. Not everyone, however, was convinced by the effect: one visitor thought the ambience too dim, for ‘the gas is placed too high and not enough distributed to be really useful’.

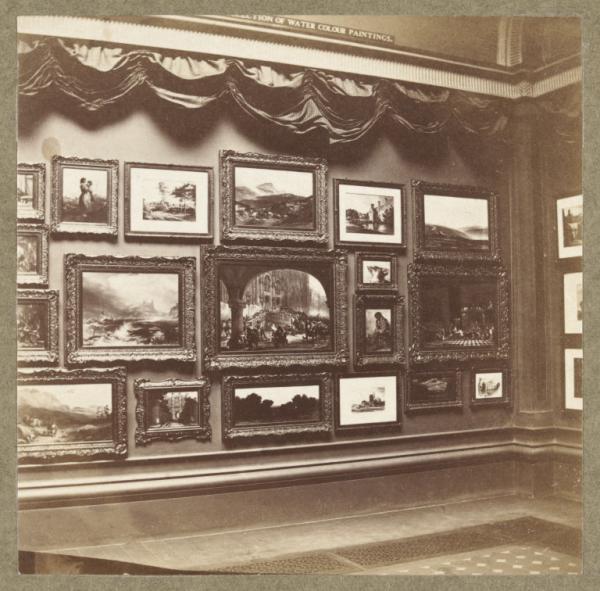

Prolonged exposure to light – natural or artificial – is harmful to objects, particularly watercolours. In the case of the Ellison bequest of watercolour drawings by British artists, the V&A installed curtains in 1864 to protect them from the damaging effects of natural light. These curtains were ‘let down at all times when the museum is closed to the public, in order that these works may be exposed to the day-light as little as is consistent with their proper public display’.

Photograph of the Ellison Gallery of watercolours, 1868. V&A Archive, MA/32/325 Guardbook neg. N2019. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1878 the V&A began experimenting with electric lighting technology for two reasons: it was potentially a more economical source of artificial light (it was estimated that nearly £140 could be saved a year lighting the Raphael Gallery) and was ‘free from the defects in lighting by gas’.

Initially there were technical problems to overcome – e.g. trials of the Jablochkoff lamp revealed that it emitted a light ‘rather too blue to be becoming to ladies complexions’ – but by 1883, Colonel Festing, the V&A’s Assistant Director responsible for buildings, reported that only two picture galleries continued to use gas light.

Photograph of the Turner Gallery, 1910. The electric lighting rig was not new when this photograph was taken and probably reused the former gas track. V&A Archive, MA/32/98 Guardbook neg. 34067. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the opinion of one visitor to the V&A in 1881, electric light heightened the inherent aesthetic qualities of the objects even more than natural light: ‘In the large courts electric lamps are now used with much success. It is wonderful to note the beauty of porcelain and all objects of delicate decoration under the new light; it brings out the minute traceries better than daylight’.

hello dearnicholas

could you help me to figure out when and why some of the sky lights wad replaced by solid panels?