Humans have depicted rabbits and hares for thousands of years. Rabbit-like creatures feature in 7,500-year-old rock paintings found in Baja California; they are also prevalent in ancient Egyptian paintings and are often found on Grecian urns.

The Museum’s Prints, Drawings and Paintings Collection contains an array of images of rabbits and hares covering many of these creatures’ natural personality traits and representing much of the symbolism that these traits have inspired throughout the history of art.

One thing that has become clear to me through my investigation into the symbolism of rabbits is its complexity which is fraught with paradoxes.

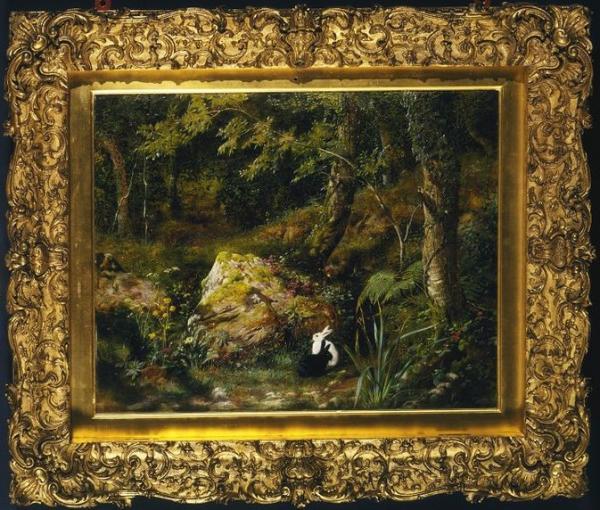

It was the Romans who introduced the rabbit into Britain. They kept them in fenced-off warrens as a source for food and fur; a practice known as ‘cuniculture’. Widespread selective breeding of rabbits began in the Middle Ages during which time they were still only bred for of food and fur, not for companionship. Although there is evidence to suggest that some wealthy medieval women kept pet rabbits, their widespread emergence as a household companion did not begin until the Victorian era. This painting by Robert Collinson hints at this shift in the relationship between humans and rabbits showing two escaped pets that have found themselves in the middle of a wood.

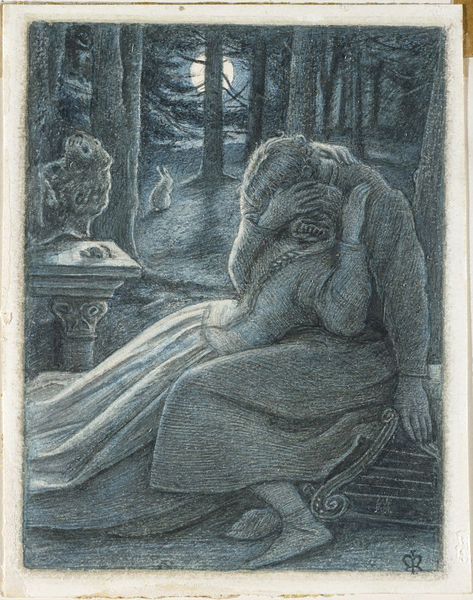

Love, John Everett Millais, ca. 1862. Museum no. 178-1894. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Rabbits have paradoxically been used as both symbols of sexuality and virginal purity. They have been a sex symbol since antiquity. In ancient Rome rabbits were frequently depicted as the animal of Venus. Conversely the rabbit was used by artists of the Middle Ages and Renaissance as a symbol of sexual purity and was often depicted alongside the Madonna and Child. In the above work by Millais it could refer to either – or cleverly allude to both.

Millais’ watercolour was commissioned for an illustrated edition of Poets of the Nineteenth Century to illustrate the poem ‘Love’ by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The poem tells of a moonlit meeting between two lovers. To a contemporary reader the poem’s content would have seemed quite risqué due to a woman meeting a man so late at night flirting with him and embracing him. Despite this deliberate attempt to titillate his audience, Coleridge repeatedly emphasises the heroine Genevieve’s modesty and virginity. This cannot be easily conveyed through one pictorial scene so it is possible that Millais added the rabbit to serve at once as a reminder of Genevieve’s virginal purity whilst alluding to the more intimate, and controversial, connection between the lovers.

This rather gruesome, darkly humorous and absurd representation of hares roasting a hunter was inspired by the popular trope of ‘the world turned upside down’, with its use of ridiculous role reversal imagery. Again this image is illustrative of the paradoxical nature of the symbolism of rabbits and hares by simultaneously alluding to the cowardice of the animal whilst also revealing the fear rabbits instilled in some cultures. Because of the hares association with cowardice, connected to the animal’s natural tendency to be fearful of predators, the imagery of the hares roasting the hunter was perhaps the most absurd the artist could think of, particularly as one would normally think of rabbits as the hunted, rather than the hunter! In addition, in Christianity, rabbits were often thought to be witches’ familiars, making people fear them. Therefore, perhaps the hares in this image could be burning the men who persecuted them.

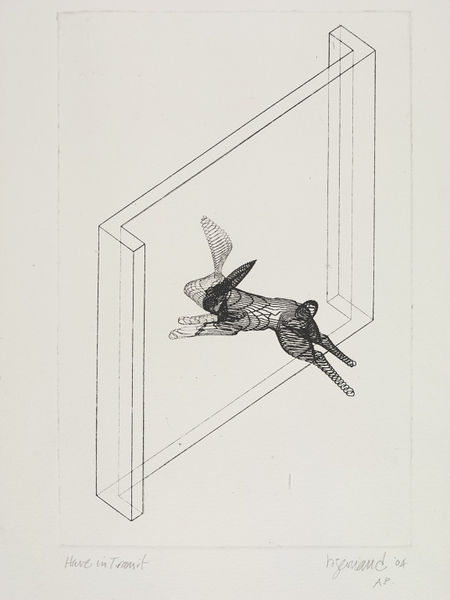

Hare in Transit, Bruce Gernand, 2004. Museum no. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Bruce Gernand.

Rabbits and hares still feature in contemporary art practices including computer art. Based on Aesop’s Fable ‘The Tortoise and the Hare’, this work by Bruce Gernand uses the hare as a vehicle to represent the relation between the virtual and material. The hare in this case is representative of the speed of computers and computer processes.

This round playing card adorned with hares is part of a set from around 1500. Although rabbits and hares have long been a favourite subject in studies of nature card engravers usually depicted animals and plants from model books. However, in this case, the hares have been drawn from nature. This may be why these hares are so lifelike in terms of their poses with distinct personalities and characteristics –although some are a little menacing looking – sniffing the ground, standing to attention and looking around with curiosity.

The symbolism of the hares in these cards remains a mystery to me, if indeed there is any symbolism intended at all. What is the significance of hares as a suit? Could it be for their decorative appeal? Or was there perhaps some deeper meaning that has been lost over time?

Thank you Anna. Do you have an idea of why rabbits would be depicted on the waste bowl of an American silver tea service, c. 1852? Each piece of the service is engraved with an emblem or scene related to its function, such as a cow on the creamer. Not sure why rabbits would be though appropriate for the waste bowl.

Hello Bradley. Sounds like a very interesting tea service. It would be really helpful and interesting to see some photographs, if possible. Please send them to our metalwork enquiries at metalwork@vam.ac.uk (you can mention my name so the enquiry is forwarded to me). Many thanks.