In our last post, we discussed the various issues that can affect autochromes, including green spotting and damage to the autochrome’s emulsion via cracks or delamination. This time, we explore how these issues can, or can’t, be addressed.

Autochromes are extremely fragile and susceptible to environmental changes. Every autochrome consists of multiple, delicate layers, and feature fugitive dyes with a tendency to alter, or bleed, when they come into contact with solvents, including water. For this reason, treatment options for autochromes are limited. Furthermore, some issues cannot be addressed: changes to colour, such as greening or orange spotting, are permanent.

For autochromes with cracked or damaged glass, one method of conserving the plate involves sandwiching the damaged fragments between two new pieces of glass. Any treatment of this kind should incorporate borosilicate glass, which is more inert than other types of glass, and therefore safer to use in the autochrome package. While this method stabilises the plate, damage caused by the cracks will still be visible.

When it comes to caring for autochromes, the best approach is one of preservation measures that can stop or slow down potential damage. This requires limiting the autochrome’s exposure to light, heat and humidity, and the potential for damage via handling.

The work on the V&A’s autochrome collection, began in 2019, not only involved scoping and cataloguing the collection, but re-housing most of the plates as well. Each plate was housed in an individual four-flap folder, made from material suitable for the long-term storage of photographs. These housed plates were then stored in boxes which were packed and padded to reduce the plates’ movement. Boxes were then returned to the photographic stores, which are temperature- and humidity-controlled.

Where plates are missing cover glass or have damaged sealing tape, further measures can be taken to limit their exposure to moisture and external pollutants. We first need to determine whether the cover glass is indeed missing – or if the plate never actually had cover glass. For example, Mervyn O’Gorman’s ‘Christina’ plates do not show any evidence of original cover glass. In these instances, a decision needs to be made whether to be faithful to the plate’s history, and the artist’s intentions, or to undertake the conservation measures necessary to ensure its future safety.

If autochromes have damaged sealing tape, the tape can be fixed. The stability of the tape is important, as it binds the autochrome plate to its cover glass, while also acting as a protective seal around the edges.

When working on the autochromes in the conservation studio, access to the objects had to be balanced with minimising light levels. To do this, a card hood was made to shield the autochrome.

The many limitations around the conservation of autochromes underline the significance of the PERCEIVE project. As there is little that can be physically done to address historic damage to autochromes, digital interventions become a useful and viable approach to understanding what autochromes may have originally looked like.

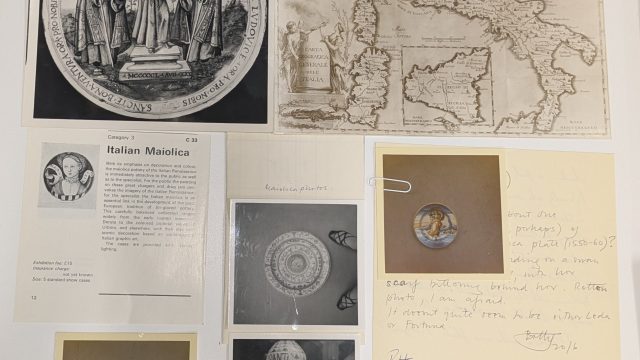

Currently, PERCEIVE is undertaking research to further understand the unique components of the autochrome. One approach is looking at separating the contribution of the gelatine silver layer from the colour filter, through high-level imaging. Early examples of this digital separation are shown below. This research could help determine whether damage – such as fading or greening – impacts both the colour and silver layers.

This research will inform the use of emerging digital technologies, with the aim of virtually restoring autochrome plates.

We look forward to sharing more of this research with you in the future.