This year has seen many exciting changes in the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries, as a large number of manuscripts and printed books on display were replaced with ‘new’ ones from the National Art Library. We call these operations ‘rotations’, in curator jargon. Page turns and rotations are essential in the museum’s permanent galleries to ensure that fragile material, such as illuminated manuscripts or hand-coloured illustrations, does not get over-exposed to light.

In January 2018, all prayer books and detached illuminated leaves on display in the case dedicated to Personal Devotion: 1300 – 1500 (Gallery 10) were replaced with a ‘new’ selection from our collections.

This case contains, alongside an amazing little ivory booklet which you should not miss, numerous books of hours, a type of prayer book which flourished from the mid 13th century to the mid 16th century in Western Europe. This book, intended for the laity, takes its name from one of its main textual components, the Hours of the Virgin. The Hours of the Virgin, like the monastic office, were divided into eight hours, from Matins to Compline, meant to be said at different times of day. The library has a rich collection of over seventy manuscript books of hours (13th-16th century), so we had plenty to choose from.

We selected:

- a book of hours typical of the early 15th-century Parisian production whose colours are still so vibrant, after six hundred years (Museum no. MSL/1902/1646 (Reid 4); fig. 2). At the beginning of a passage from St John’s Gospel, the Evangelist is shown accompanied by his symbol, the Eagle. He is busy writing on a scroll, and one would expect it to be his account of the life of Christ, but the first words, clearly legible, are those of the Our Father prayer (‘Pater noster qui est in celis’)

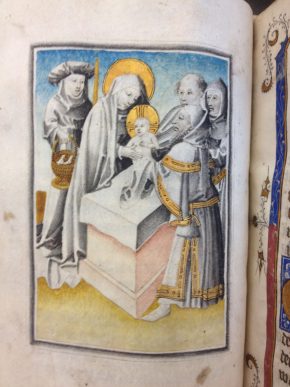

- a mid 15th-century Netherlandish book of hours written in Dutch, illuminated in a semi-grisaille technique, with the figures painted in shades of grey contrasting with gold and vibrant colours used to highlight details and background (Museum no. MSL/1902/1667 (Reid 32); Fig. 3)

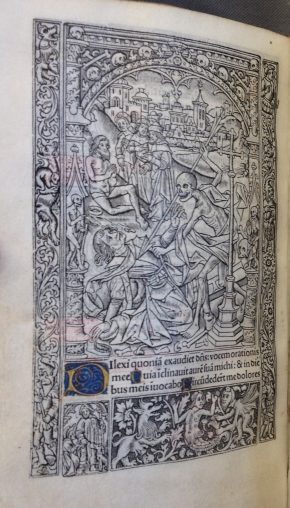

- a book of hours printed in Paris in 1503 by Thielman Kerver, with small painted initials added by hand in red, blue and gold (Museum no. 38041800982431; Fig. 4). From the mid 15th century onwards, a new means of book production developed in Western Europe following the invention of the printing press. France, and especially Paris, specialised in the production of printed books of hours teaming with illustrations. To give an idea of the scale, 299 editions printed in France have survived for the period up to 1500 alone. This is an enormous output when compared, for instance, with the 74 surviving editions printed in Italy, in spite of a head-start, with the first extant Italian examples dating back to the early 1470s as opposed to the mid 1480s in France (C. Dondi, Printed Books of Hours from Fifteenth-Century Italy, Florence, 2017, p. 7).

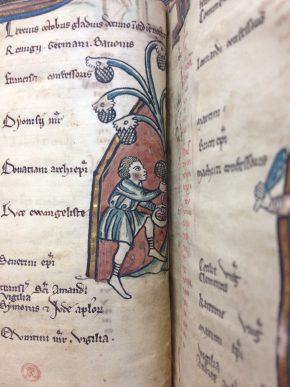

Before the book of hours came into fashion, the psalter was the prayer book of choice, so we included a late 13th-century Flemish example in the display (Museum no. MSL/1902/1664 (Reid 24); Fig. 5). The psalter is one of the books that compose the Bible; it contains the full book of psalms, commonly attributed to King David. Psalters, like most liturgical books, began with a calendar indicating which saint to celebrate on which day. This section was usually illustrated with the labours of the month. For the month of October, a man is shown here harvesting strange fruits from a fantastic-looking plant.

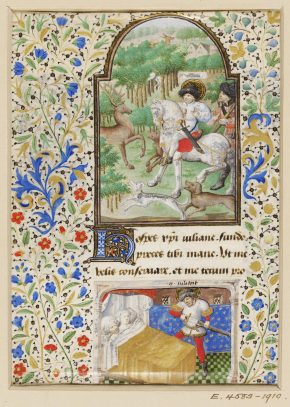

The V&A also has a large collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscript cuttings: sometimes a full page, sometimes an initial, a miniature, a snippet of border. 19th-century collectors were particularly keen on assembling collections of fragments of different dates and origins, or pieces attributed to well-known painters, and the market catered for them. In the context of the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A was then named), these pieces were acquired to serve as sources of inspiration for artists and craftsmen. They also charted various styles and regional schools. Three individual leaves from 15th and 16th-century French books of hours have been mounted on the wall at the back of the case: two come from a Parisian 15th-century book of hours attributed to the Dunois Master (Museum no. E.4583, Fig. 6), and the third one from a Rouennais early 16th-century hours (Museum no. 9004J).

Next time you visit, come and explore the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries to see these fascinating books in person!