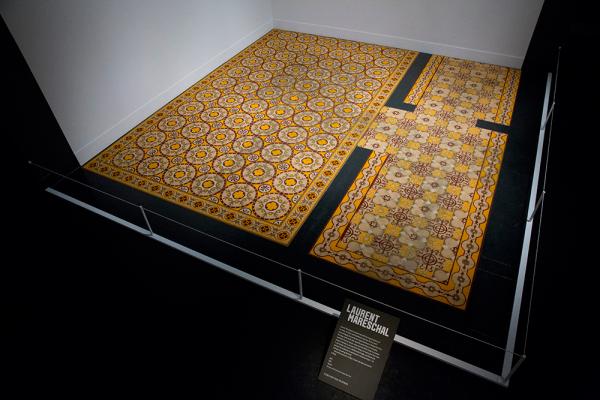

One of the more unusual activities for us in the conservation department this week was to restore damage to Laurent Mareschal’s Jameel Prize installation ‘Beiti’. The curious fingers of a member of the public (undoubtedly interested in confirming that Mareschal’s intriguing tiled floor pattern was in fact made with spice and not ceramic tiles) had badly damaged the edges of the work.

We normally frown upon having foodstuffs in a museum gallery – it’s a banquet for pests – but in some artist’s work, like Laurent Marschal’s, it has great significance, is part of the overall experience of the work, and we work closely with those artists to ensure their work (and our collections) are not at risk.

Mareschal’s work is concerned with impermanence. His large, ephemeral, site-specific works draw on everyday materials such as spices, soap and food. With these he creates patterns based on, among other things, the decorative floor tiles in old houses. His work is deliberately fragile, and Mareschal expects his audiences to participate in transforming it – for example, by eating the food. Taking care of these fragile site-specific and transient works requires a slightly different approach to how we define damage and how we address it.

Marschal’s entry into this year’s Jameel prize is ‘Beiti’. Emulating traditional Arabic geometric patterns it is a tiled floor created solely from spice. More particularly it is made with ginger, turmeric, sumac, white pepper and za’atar sieved carefully over laser cut Perspex stencils. It’s a time consuming and intricate task, as you can see in this time-lapse video of the installation:

Mareschal is interested in the short lived nature of this work. He is happy for the spice floor to slowly fade over the duration of the exhibition. However with such a fragile work, we also expect that some damage will occur that does not come under the remit of the artist’s wishes, and when this happens it requires our attention. At first glance, the floor looks very similar to a ceramic tiled floor, and the fact that it isn’t is not immediately obvious just by looking at the work from behind its barrier. This has been an issue when the work has been installed at other venues, as he points out:

“The first time that I made it, we didn’t put a rope around it so people just walked on it and ruined it completely as they thought they were real tiles. So I want people to look and think OK, they are real tiles and suddenly if they look another time they will realise it is made out of spices and it will surprise them.”

Part of that surprise must be an initial disbelief, quickly followed by the desire to touch perhaps to confirm that what we see and are being told by the label is true. Of course, most visitors abide by the traditional “Do Not Touch” warnings, the physical barrier, and the stern faces of the V&A’s gallery assistants, but for some – and to be fair it’s not surprising – the need to touch is overwhelming.

Damage to objects from curious hands doesn’t happen often thankfully, but with an installation as fragile as this, we expect it, and we can plan for it working together with the artist to decide when ‘damage’ becomes an issue for the appreciation of the work, and how to deal with it.

This is decided prior to the installation of the work, and in the case of ‘Beiti’, Mareschal confirmed that he was happy for our conservators to restore any physical damage to the spices using his technique.

So this morning, armed with a set of Mareschal’s original stencils and some several very large containers of spices (we like to be prepared for any contingency), Conservator Chris Gingell carefully removed the damaged area with a brush, replacing the missing areas by applying new spices with a sieve through the artist’s stencils:

The stencils float above the surface of the floor on the points of screws so that they can be lifted up without disturbing the surrrounding areas:

Because the damage interrupts the entire pattern, several stencils are used in a particular order to restore the damaged area. Here Chris adds a layer of sumac followed by a layer of ginger:

And afterwards one might never know there had been any damage at all:

Laurent Marescal’s installation can be seen in the Jameel Prize 3 exhibition in the Porter Gallery until 21st April 2014.

The Jameel Prize is an international award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition. Its aim is to explore the relationship between Islamic traditions of art, craft and design and contemporary work as part of a wider debate about Islamic culture and its role today.

I never realized that decorative floor tiles are now seen to have the value it deserves. Having the time to make the history be restored to be seen and displayed by many will surely inspire the inside artist in you.