[Stained glass] is a very limited art and its limitations are its strength. (Edward Burne-Jones, 1897)

The qualities needed in the design […] are beauty and character of outline; exquisite, clear, precise drawing of incident. (William Morris, 1890)

In my previous post, I looked at some early stained glass designs, and mentioned how the established techniques of stained glass manufacture largely died out in the 17th century.

In the 19th century, a reaction against increasing industrialisation and commercialisation led people to look to the past for inspiration from simpler times. There was a resurgence in interest in all things medieval, including stained glass, and the Pre-Raphaelites in particular were heavily influenced by medieval themes and imagery. In 1861 William Morris set up his company Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co, known as ‘the Firm’, to provide fashionable families with everything they might need to furnish their homes in the new Arts and Crafts style. One of their biggest successes was stained glass, and they took private domestic commissions as well as replacing church windows all over the country.

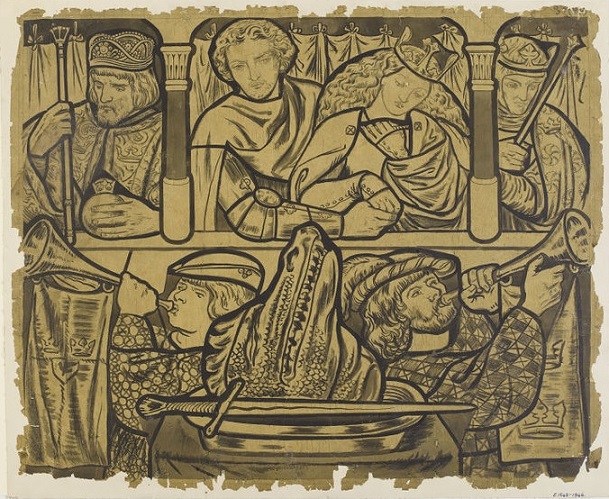

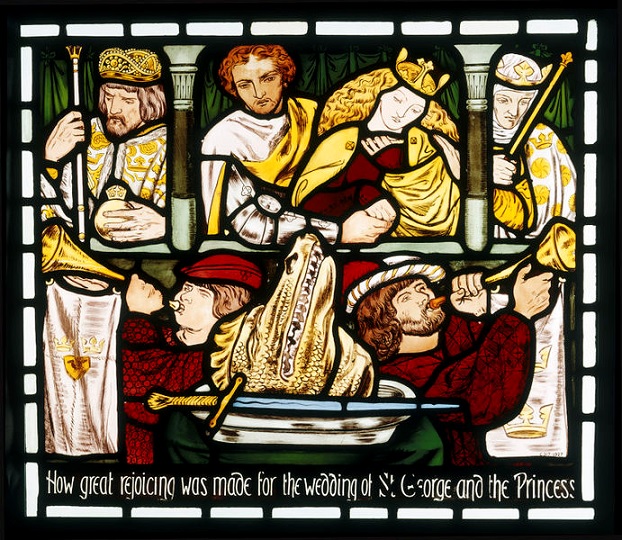

Morris used his friends – often members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, Philip Webb and Edward Burne-Jones) – as designers. The company’s first commission was a window telling the legend of St George and the dragon, for which Rossetti did the designs.

I love this design, which perfectly illustrates how glass of this period combined medieval influences, in its subject matter and dramatic design, with Pre-Raphaelite characteristics, particularly Rossetti’s distinctively strong female faces.

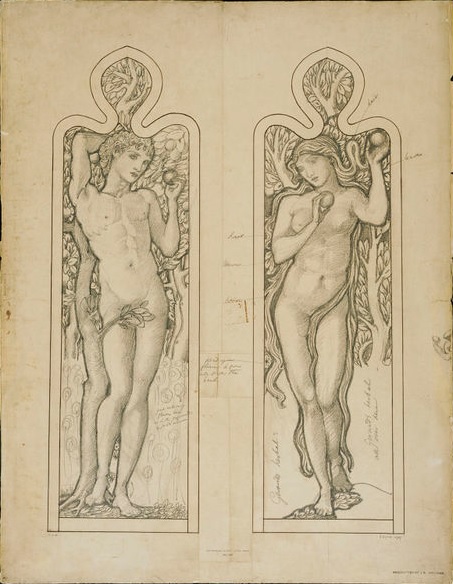

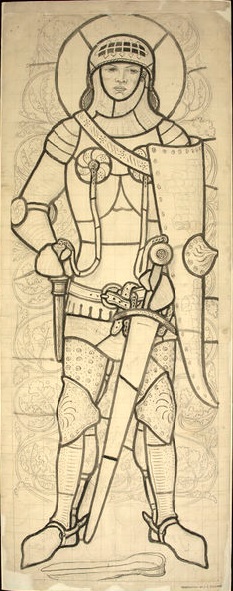

In most cases the 19th century artists did not execute the stained glass themselves: their designs were passed on to glass painters, for example those in Morris & Co.’s workshop. In this design by Edward Burne-Jones, Morris’ main designer from the 1870s onwards, the artist has left notes for the glass painters about different elements of the design. At the bottom of the ‘Adam’ panel, hastily sketched flowers are accompanied by the note ‘put millions of flowers here…’. The artist therefore relied on the craftsman to realise his vision.

Drawings such as the one above were commissioned by Morris & Co., and were then added to a catalogue of designs. They could then be reused or adapted in different locations; particularly in the late 19th or early 20th century, some windows were pieced together from cartoons originally produced in many different years.

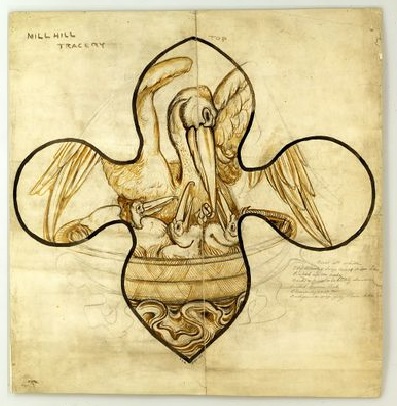

Even individual designs were sometimes worked on by several different hands. In the Adam and Eve panel above, Morris himself may have filled in the background, with his genius for turning natural forms into repeating patterns. Philip Webb, the Arts and Crafts architect who designed Morris’ Red House, was particularly talented at drawing birds, and artists sometimes left spaces in a design for him to fill in the birds!

Once the design was complete, it would have to be enlarged to the actual size of the window, so that it could be used as a template for cutting and painting the glass. The design shown below was enlarged from the original drawing to a sheet a metre tall using the grid method.

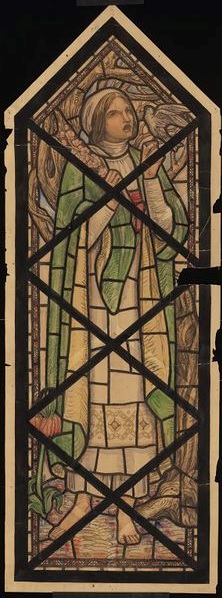

Finally, I wanted to mention Mabel Esplin (1874-1921), one of the few female stained glass artists I have found during my research. She was part of the Arts and Crafts movement, although not directly connected to Morris, and was also an active member of the Women’s Suffrage movement. Her largest commission was a series of windows for All Saint’s Cathedral in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum in 1912, one of which you can see below. Sadly she was taken ill in 1916 and was unable to finish the commission – it was taken over by her former assistant Joan Fulleylove. The cathedral was confiscated by the Sudan Government in 1971 and turned into a museum, but fortunately the stained glass windows have remained intact. I haven’t been able to find out much information about Esplin, so if you have any more, please do get in touch.

Watch this space for my final post in this series, which will look at the variety of reasons that people have made drawings of existing stained glass windows, from using them as inspiration for their own art, to recording damage caused in a bombing raid.

I would like to know if is possible to find copies of St George cartoon….

I have been creating stained glass patterns for over 20 years. I have created a website to showcase my work and also others. This is an example of more modern stained glass. http://www.anypattern.com

I have a pre raphaelite cartoon/design of Chaucers Canterbury Tales. It’s an original drawing, and I am trying to

find out who did the design and if the original still exists. Can I send images to the V and A? Thanks for your help.

Hi Sarah

Fascinating article. During your researches have you come across a list of churches with windows by Morris or Whitefriars at all?

Graham

Is this true that stained glass on paper morris is possible.