This blog is written by Roberta Zanini, PhD student from Ca’ Foscari, University of Venice, and explains why Roberta is spending a few months at the V&A examining our glass objects.

Why do certain types of glass corrode?

This is still a mystery: despite numerous studies that have focused on the interaction between glass and the environment, the mechanism of glass corrosion is not fully understood yet.

There are many factors involved in the process of glass alteration, affecting also the speed at which it occurs. They include the composition of glass itself, temperature, pH, and the amount of available water in the environment among other things.

Why the V&A?

As part of my PhD, which I am carrying out at the Centre for Cultural Heritage Technology (CCHT-IIT) and the University of Venice (Italy), I am spending four months working with the V&A scientists in the Conservation Science Lab. The Lab has been recently revamped, and one of the new pieces of kit is a hand-held X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer which we are using for the non-invasive characterization of glass objects from the V&A collection.

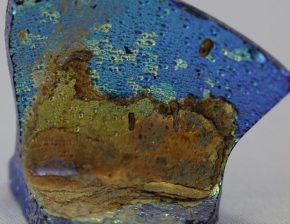

The aim of my project is to investigate the composition of a number of V&A objects and verify their state of conservation. I am selecting the glass objects considering the different types of alteration that are visible on their surface (crizzling, iridescent patina, pitting), and I am hoping to correlate the specific glass composition (and therefore the period and place of production) with a characteristic type and degree of alteration.

Nanotechnology to the rescue

At the same time, I am part of the research and development of an innovative glass consolidation treatment based on nanotechnology. The treatment is part of a new generation of sustainable, eco-friendly products, and is non-toxic both for the operators and the environment. Since it is also 100% compatible with the vitreous material, it guarantees great adhesion to the glass substrate, and long-term stability.

At the V&A I have access to a few fragments of deaccessioned museum objects, and I am going to test the nano-treatment on them. After I deposit the consolidation treatment on the fragments, I will put these in an environmental chamber, subjecting them to high levels of temperature and humidity. This will allow me to evaluate the treatment’s resistance and its ability to confer more chemical stability to glass objects exploiting the advantages of nanotechnology.

Stay tuned, and I will update you with the next steps of the project.