I was recently asked to work on a very unusual object, which was a 19th century Tibetan drum, made of human skulls. The drum was about to travel to the Wellcome Collection’s exhibition titled; ‘Tibet’s Secret Temple; Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism’. It was highly exciting to work on this loan as His Holiness the Dalai Lama, himself has given his special blessing for the show.

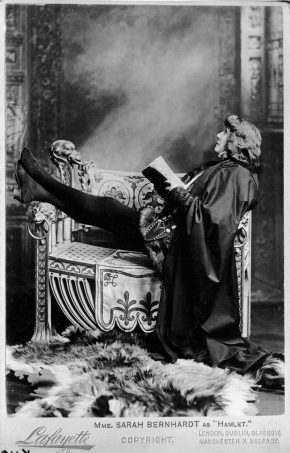

Although a colleague had recently assessed the skull that was used by the actress, Sarah Bernhardt (1844 – 1923) in a production of Hamlet, handling objects made from human remains is a rare occurrence in the V&A. Being in close proximity of human remains invokes pertinent feelings of mortality.

Working with such material prompts many questions: whose skulls were they? Why were they made into a musical instrument!? Was it ok to handle this object? Was it sacred? And how did it come into the Museum?

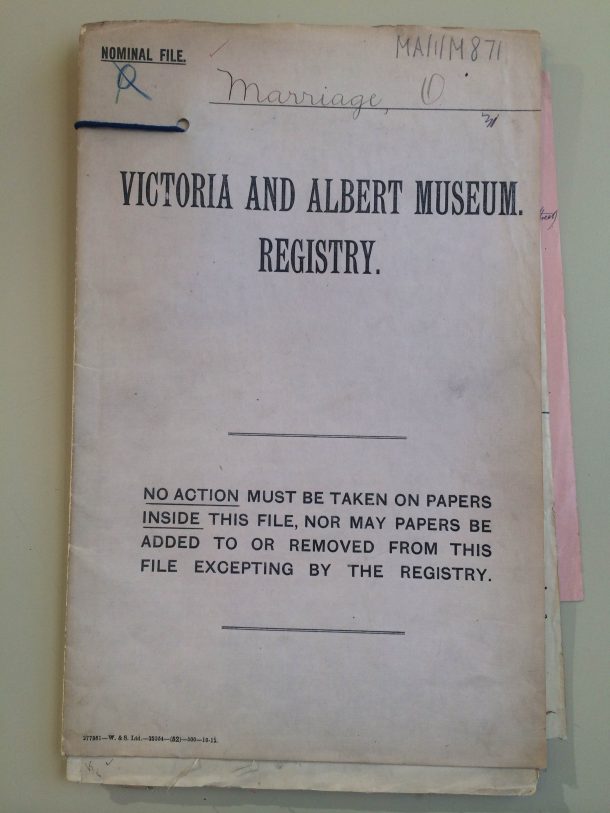

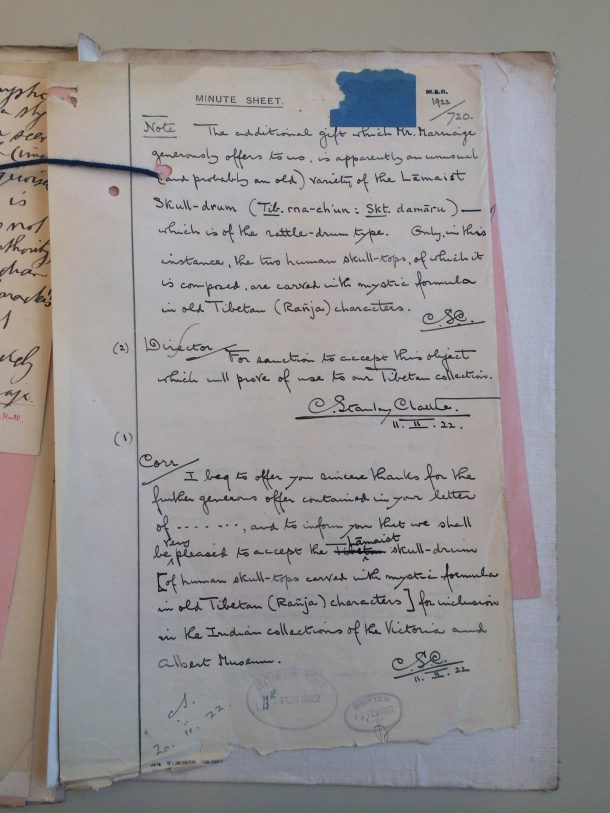

To find out where the drum came from, I requested the registered files, which contains the acquisition information.

It turns out the drum was given to the Museum in 1922 by Octavius Marriage Esq of Hampstead along with other objects including a necklace made of human bones and a frontpiece from the Ngakpas, who are lay tantric practitioners usually of the Nyingma sect.

Dr. John Clarke, Senior Curator, South East-Asian Department (specialising in Buddhist material) said that there are a few possible scenarios, familiar to him from other objects, for how this piece got into our collection. The date of accession is just 18 years after the British military expedition to Tibet, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Francis (later Sir Francis) Younghusband. This now notorious event started as a diplomatic mission to engage the Tibetan government in talks designed to open trade and diplomatic contact with what was then a closed country. In the wake of the mission fighting its way to Lhasa there was a great deal of object collecting which included both looting (from any monastery that resisted the British) and buying (from any that did not resist). It is impossible to say now if these pieces came from the expedition as the papers provide no clues and only a very few items in the V&A’s collection do actually come from it. However the result of the Treaty of Lhasa signed by the Tibetan and British sides afterwards led to the establishment of trade stations at Yatung, Gyantse and Gartok in Tibet and the succession of diplomats posted to these places with their military escorts and staff led to a great deal of the collecting of Tibetan memorabilia. These things were often kept in the families for decades before they were eventually given, or sold, to museums such as the V&A. It’s also worth mentioning that Tibetan objects such as these were also sometimes traded out of the country or brought out by pilgrims visiting India in the late 19th and early 20th century.

After learning about the origin of the gift by Mr. Marriage, I set off to work to compile a report, that travels with the object stating its condition and highlighting its composition. This report was used by the courier Diana Heath, a Senior Metalwork Conservator, who was chosen to accompany the object in transit and installation, because of the Mahasiddha Virupa (made of copper alloy) is also being lent to the exhibition (The sculpture is normally on display in The Robert H.N. Ho Galleries). Diana had conserved and studied the Virupa figure in 2012 and had published an article in the V&A Conservation Journal about her treatment and findings.

The drum also needed cleaning, so it would look its best once on display.

Naturally intrigued, to discover more about the meaning of this particular piece, I set off on a journey to discover the current codes of ethics when working with sacred human remains as well as the meaning of Buddhist rituals, sacred musical instruments and the materials that were used to make this drum, including semi-precious stones.

Current codes of ethics

Human remains are found in museums across the world. The International Council of Museums ICOM has strict guidelines on how to handle human remains respectfully.[1] Museum staff, including conservators, use ICOM’s code of ethics as the basis for their modus operandi when conserving, housing and displaying all types of objects and especially those that are of cultural importance, sacred or made up of human remains.

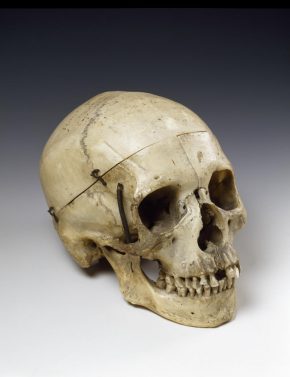

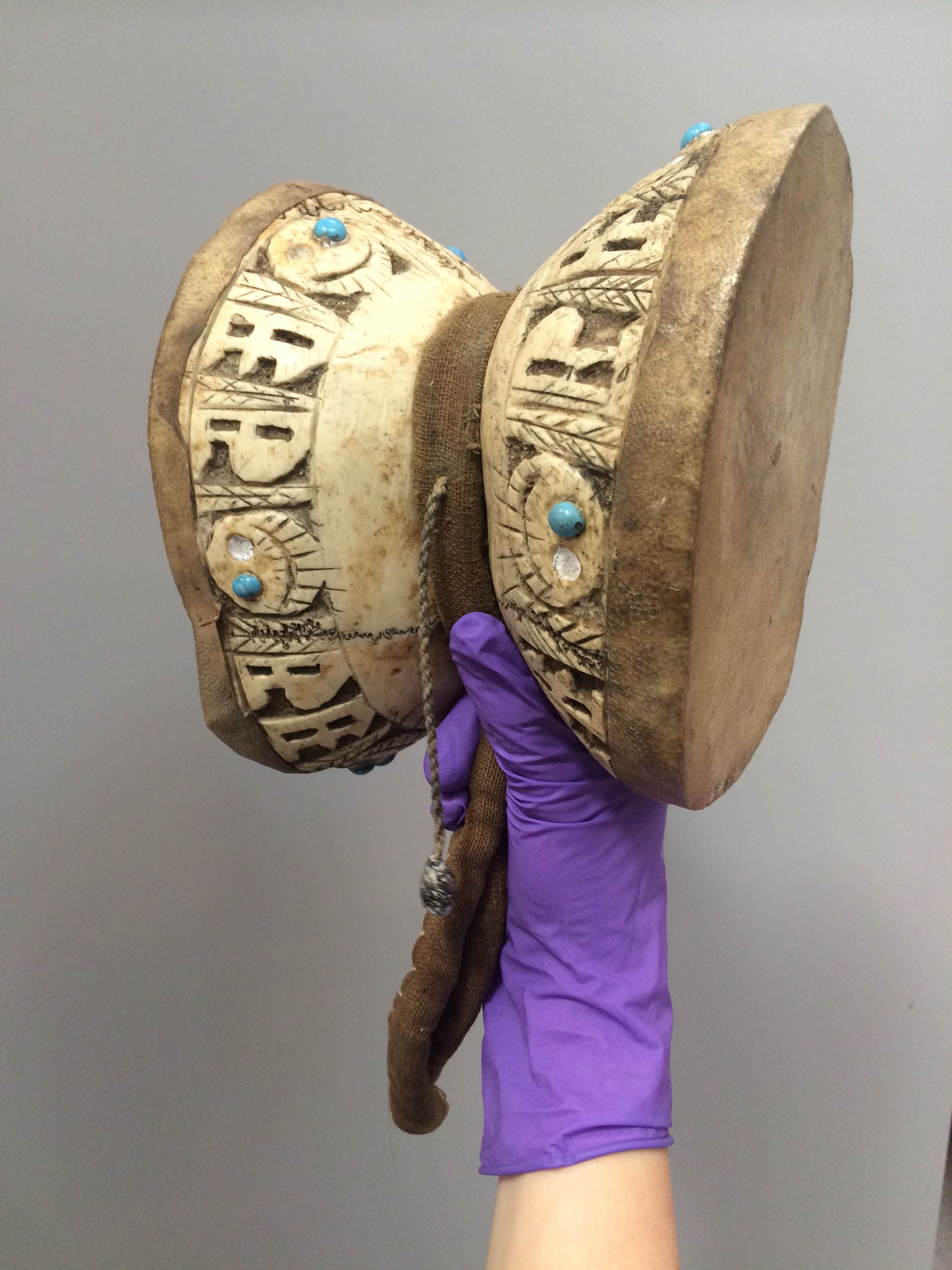

Composition and condition of the drum

I had a close look at the drum to check its condition to see whether its components were stable and at the same time tried to work out the meaning of its motifs. The skull components are from the cranium, the part of a skull that encloses the brain. Parchment was stretched over the skulls to form the drum skin. One of the craniums appeared slightly larger than the other. The skulls were roughly carved with interesting motifs resembling lettering and ‘happy faces’ with engraved straight lines pointing downwards, seemingly mimicking the rays of the sun. The ‘happy faces’ have in-set turquoise-coloured beads, and although some were missing, the remaining beads were firmly stuck in place. The cotton cloth, with its crude but neat stitching, was tied in between the two skulls, and formed a loop for holding the instrument. At close inspection, the most vulnerable areas appeared to be the two so called ‘strikers’, which were wax coated pellets attached to two rather fragile looking cotton threads.

Examination and conservation of such a complex object often involves more than one conservation discipline. For example, colleagues from Paper, Book, Metal and Sculpture Conservation all took part, as well as curators. As I was no expert in verifying the condition of the parchment, which covered the skulls, I invited Alan Derbyshire, Head of Paper, Books and Paintings Conservation, to take a closer look. Alan examined the parchment skins (possibly goat) under magnification and confirmed they were in good condition.

Senior Metals Conservator, Joanna Whalley, who specialises in gemstones and jewellery examined the turquoise beads. She noted that some of the beads appeared to have been restored in the past, as there were specks of modern glue on the edges. Other beads were set in some sort of white plaster type substance or gesso, which is not an unusual material for setting decorative parts to objects. A closer look at each bead proved that they all had gas bubbles and dark swirls inside, indicating they were made of glass, since real turquoise would have neither. Glass (as well as ceramics) are commonly used as substitutes for natural turquoise.

Buddhist rituals & sacred musical instruments

Curious to know more about the motifs and why the drum was made using craniums, we asked the opinion of Senior Book & Paper Conservator, Anne Bancroft, who is specialising in the conservation of Buddhist art at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

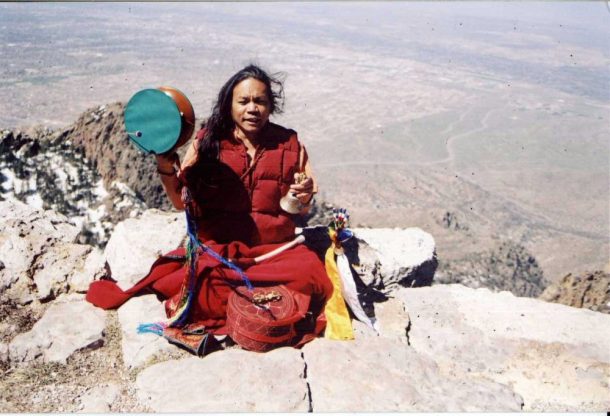

Anne explained that the drum was a sacred tantric ritual instrument ‘a hand-drum or damaru’ used most likely in the Tibetan Buddhist ritual practice called ‘Chod’. Chod is normally associated with Vajrayana Buddhism and is a type of meditation practice to cut through our ego.

In order to explain the meaning and context of ‘Tantra’ Anne mentioned that there are different types of Buddhism known as ‘Paths’ or ‘Vehicles’. There are difficulties in defining Tantra, but it is best described as the “path of transformation” it can be viewed as a ritualised and sometimes esoteric form of Buddhist practice which uses iconographic imagery/objects/visualisation, prayers, offerings and symbolic ‘mudras’ (gestures) to aid ultimately with ending ‘suffering’ and to achieve enlightenment.

John mentioned Tantra ritual practices are a mixture of visualization, breath control, ritual gestures, mantras, or words of power and ritual is characteristic. Deity yoga employing the visualization of oneself as a deity is key to the process. Wrathful deities, the embodiment of inner forces that can overcome obstacles on the path are often shown holding skull cups and dressed in bone jewellery, These all have strong symbolic meanings, for example skull cups also symbolize emptiness and bliss. Another ancient Indian tantric aspect of the use of bones in rituals or for eating from or dressing in is that the user of them is showing he/she has transcended the opposites of dirty and clean, good or bad having reached a level of being and understanding in which those opposites don’t exist.

Although accustomed to seeing wooden damarus and while she knew that skull ones existed…. Anne had never actually seen one before. She thought that some of the carvings were likely to be a specific mantras – the catalogue record states that the script is carved using Ranja characters, which is an adaptation of an ancient Newar script often used on ritual objects from Tibet . The damaru was originally associated with the God Shiva, and in India was often referred to as the ‘monkey drum’. Damarus tend to be covered in vellum made from goat, fish or even snake skin. (Beer)

Anne commented that the ‘tassel’ or five-coloured silk valance tail was missing. You can see in the images below how the complete darmaru is supposed to look.

But, I still wanted to know why they used human skulls? It turns out that in Tantra the skull is recognised as a symbol which represents bliss and impermanence. In the curious case of the Tibetan skull drum or damaru the ‘…skull symbolises the union of method and wisdom as relative and absolute bodhichitta’(awakend-heart-mind).’ (Harding)

The ‘union’ gives us the hint about why one cranium is smaller than the other – traditionally the skull damaru is made from the craniums of a boy and girl that have had a ‘sky burial’ (instead of a cremation). The male and female union in Vajrayana Buddhism is symbolic of compassion and wisdom. The use of the skulls in the ceremony would be culturally thought to be very fortunate.

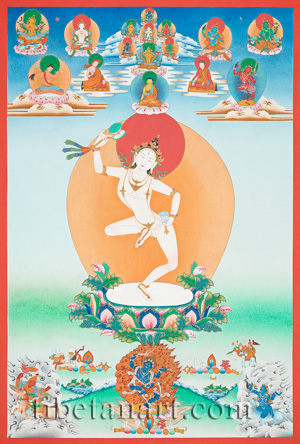

Here you can see a depiction Machik Lapdron, is the founder of the Chod teachings – one of the few unique spiritual lineages with a female founder (of any spiritual tradition).

What started out as a routine loan request to prepare an object for exhibition ended up as a fortunate opportunity to collaborate, using our in-house areas of expertise. We all found it a fascinating investigation into understanding what could have been easily misconstrued as a ‘just an unusual musical instrument’. Instead, we discovered that this drum is a highly symbolic representation of method and wisdom.

In the right hand of a skilled Chod Buddhist practitioner – a ritual tool that is compassionately used in a ceremony which aims to help free sentient beings from suffering. This object will be shown in the appropriate context alongside many other types of ritual objects in Tibet’s Secret Temple.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my sincerest thanks and appreciation to Anne Bancroft and John Clarke who contributed to this blog. I would also like to thank Alan Derbyshire, Victoria Button, Joanna Whalley, Diana Heath, Victor Borges, Cherry Palmer, James Sutton and of course the Curators at the Wellcome Collection James Peto, Ruth Garde and Ian Baker for choosing this interesting object.

Bibliography

Beer, R. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols, Shambhala, 2003.

Harding, S. Machik’s Complete Explanation: Clarifying the meaning of Chod, Snow Lion, 2003

ICOM, The ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums, ICOM, 2013

Samuel, G. The Orgins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge, 2013

Smith, S. & Bancroft, A. Worth a thousand Millibands, ICOM CC, 20

Strong, J. Buddhisms: An Introduction, Oneworld, 2015

Dear Johanna, there’s an issue about this kind of skull drum around which there’s much debate. I have some question concerning that, and I wonder if you can contact me by email? Sorry this is a sensitive issue and I have to remain anonymous here.

Great article! Was wondering if you ever read of Mickey Harts personal experience w/ a skull damaru? (Drummer for The Grateful Dead/ in his book Planet Drum). My guess is this might be CYY concerns. I can provide a synopsis if desired.

I have acquired a Damaru which is incredibly similar to this one. Can you point me what I should/ could do with it? Please contact me and I can send some photos and have a correspondence.

To have a clarity of Chod one may seek guidance of Anam Thubten Rinpoche of Dharmata Foundation who recently completed a rare comprehensive Chod online retreat for Asia & a few other occasions previously. More commonly Chod is only offered as a ritual performed on behalf of individuals by Tibetan tradition monks.

This is a drum sewn from human skin! ! ! It’s not goatskin