Guest post by Kasia Maciejowska.

The House of Beauty and Culture (HOBAC) was a craft collective at the heart of the London club scene in the late 1980s. They mixed outré camp details with rough industrial textures to pioneer an urban dress code that was taken up by the fashion world in the following decade.

Stephen Phillips, owner of cult vintage fashion shop Rellik, in West London, has been collecting their work for decades, and is still excited about it: “It was all done on a wing and a prayer yet those early pieces established the details that would become their signatures and be copied by everyone from Topshop to Louis Vuitton”.

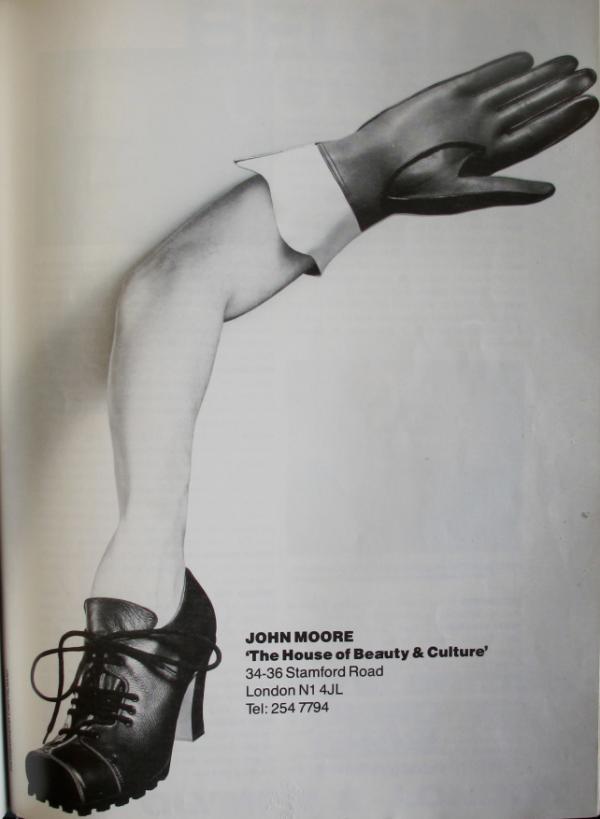

HOBAC was founded by the shoe designer John Moore. The space he found, on a residential street off Kingsland Road, East London, came with a Victorian shop below, so he invited his friends to show their work there, and to decorate the space.

Alan Macdonald, who contributed to the interior, remembers, “The most interesting thing about the shop was the floor, which was a response to having no money, because then the idea of spare change being kicked around became a concept. As you walked around the shop you crunched on it. We found it amusing.”

Among his shopmates were the stylist and jewellery-maker Judy Blame and the fashion designers Christopher Nemeth and Richard Torry. There was also the furniture making duo Frick + Frack, or Alan Macdonald and Fritz Solomon, plus other young designers who added pieces when they felt like it. And there was Mark Lebon, the photographer, who shot their work for leading street style magazines The Face and i-D.

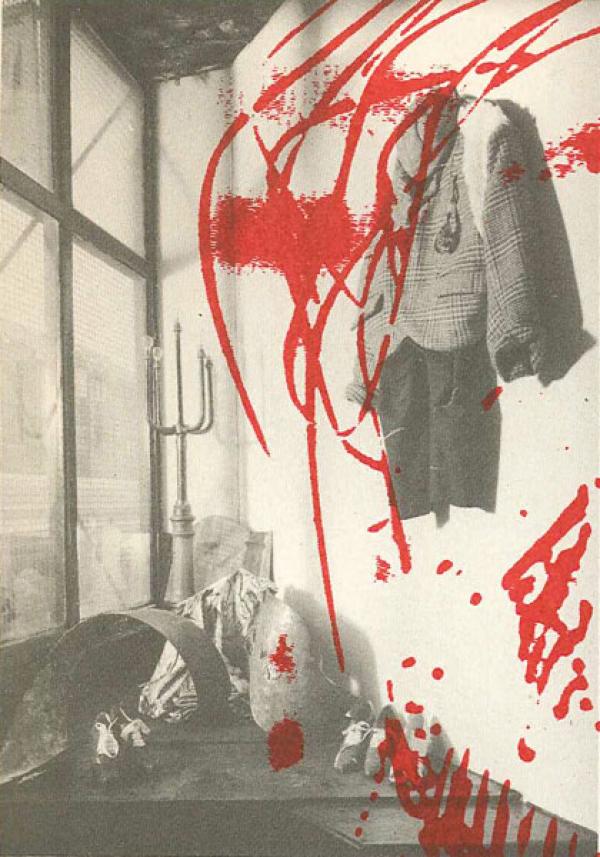

This group of young men took an ad hoc approach to their craft, collaborating when it felt right, and supporting each other as they found their feet on the London scene. Influenced by Punk and by the decaying city around them, they reworked found materials through bricolage, or 3D collage, that mashed different styles and different stories awkwardly together.

They left fabric seams exposed, kept woodwork raw, and let recycled objects remain as found. This was important because it revealed the source of each material and their own handcraft processes. In this way their design works communicated the reality of urban decay, giving them an elegiac quality that mourned a fallen England. This was a potent theme in British culture at the time and can be seen in The Last of England (1987), a film by Derek Jarman, friend of HOBAC.

By emphasising that they were handmade one-offs, their clothes, shoes, chairs and jewellery also marked them as special, and gave them an aura of the quirky and the characterful that had been lost through mass-production.

The predominance of mass production that grew during the mid-twentieth century culminated in a broad artistic rejection of uniformity that exploded in the 1980s wave of postmodern expressivity. HOBAC was a part of this, and one of several resurgent craft hubs in London that used handwork and recycling to propose an alternative aesthetic – other examples included Creative Salvage (Tom Dixon), NATO (Nigel Coates) and One Off (Ron Arad).

Of course the name of the shop is best not taken straight up, but with a pinch of the absurdist humour that amused the group and helped them convert their outsider status into craftwork and creativity. Mark Lebon explains, “It was ironic, which was important because it gave us power”.

In the 1980s the East End was an urban wasteland. The policies of Margaret Thatcher’s government were punishing for its inhabitants. Unemployment was rife. To set up a shop here, beneath a studio with no heating, to decorate it with junk and name it The House of Beauty and Culture… it was a laugh, instead of a cry, for creative energy in the harsh underside of the 1980s.

Through their craftwork they told their story and through clubbing they escaped it. London’s clubs were an alternative world where subculture thrived and junk could be fabulous.

As the disinhibition of ecstasy culture set in across disused warehouses throughout the East End, HOBAC was at the fore of creating a fashion language that merged the camp performativity of Soho clubs like Taboo and Heaven with the rough-edged post-industrialism that hosted the rise of rave.

In doing so they tested ideas – square toes, ripped seams, toy necklaces, workwear fabrics and sculptural knitwear – that would come to define the early 1990s in global fashion. Between 1986 and 1989 they explored a moment in the history of club culture where camp met macho and where casual met costume.

They struggled, they had fun, and they were the first in the fashion world to set up shop in Dalston, which has since become the hub of fashion production in contemporary London.

Kasia Maciejowska is a journalist and editor who has written for The Times and Wallpaper among others. As part of her MA in History of Design at the V&A and RCA in 2011 she wrote an in-depth dissertation about The House of Beauty and Culture, which has been used as a reference by Shaun Cole in his essay for the exhibition catalogue that accompanies Club to Catwalk, and by Gregor Muir, director of the ICA, for the current collaboration between the ICA and the Old Selfridges Hotel, which maps London subculture from the eighties to today, starting with The House of Beauty and Culture. The dissertation can be found in full in the National Art Library at the V&A.

Had a workshop down the road at the Metropolitan Hospital. Knew many of the creative names from those times. Still treasure and wear my coat from HOBAC made of worn jeans and a mermaid inside.

In the 80s I used to visit House of Beauty and Culture. I used to spend a lot of time with John Moore. Loved watching him work. A lovely guy, a brilliant designer – miss him and his shoes.

When my ex- wife decided to leave me the only way she got back at me was to take the right foot of every JM shoe I possessed.

I know John as I did would appreciate this humour LOL

I laugh at this when I think about it but I’m also pissed because they are irreplaceable.

great dayz.

Special shout out to John Moore RIP – miss you bro

I have an unworn pair of John Moore shoes size 8. There is a small blemish on one,but other than that great condition. Not sure what to do with them. Any ideas ??

Rj

I worked at the HBC as shoemaker for John Moore in 1987. My first job in the footwear industry. What an experience . Sometimes I think I dreamed it.. I have been a shoe designer ever since.

Hey mark Rogers, Ian here…long time no see… Got to say John would of had a sneaky appreciation of your wife’s approach to revenge… it’s refreshing to read something honest and accurate about hobac…same to you Andrew Davies… you clearly know about Alans amazing work.post fric and frac and the hobac days… not enough is

Written about him or Fritz

Rose… .

. I recently decided unfortunately for you… that I can no longer remain silent and have to speak up when I come across mistruths inaccurate articles.. stories.. anecdotes about john…me.. Fritz & hobac ….

Your not the first and it’s a certainty you won’t be the last …

If you had asked I wouldn’t of been able to recall your name… But even though it was 40 odd years ago I haven’t forgotten your work experience car crash… memory serves you were doing shoe design at Leicester…you turned up unexpectedly and was told to return the following day… God knows what you were expecting…not us… John asked you to do his shopping or pick up his dry cleaning…. your reaction… that you haven’t come there to do someone’s shopping etc… John was his usual colourful direct blunt self…you left in tears never to return.. you managed to survive two or three days at the most…. We used to receive scores and scores of requests from students and colleges..but after you we only had one other student come for work experience…she had come all the way from some German design school and didn’t even make it past the first mornings tea break before she left in tears…

As such I would suggest your slightly sketchy recollection was more of a nightmare than a dream…

I’m glad you r experience with us didn’t stop you pursuing your career…. please just be honest in the future…