My childhood collection of comic books survived intact until I was poised to start studying architecture at the University of Cape Town. My big problem was; my mother disapproved of the comics. Mom wanted a law passed against grown boys reading comics. My father said that was enough, and mom kept quiet.

L Mabusela never had a bad word to say about comic books. Confined to my sickbed I was constantly looked after by her. L Mabusela was not merely a servant. She was the heart and core of the household.

Growing up I lost the asthma but stayed attached to L Mabusela. Towards the end of the 1950s I was a thousand miles away near Pretoria on The Hellions; a British cowboy flick on location. When I returned to Table Mountain L Mabusela was gone, dismissed during my absence. This was a few months before the Sharpeville massacre. The Sharpeville murders were a brazen declaration; South Africa was a police state. My political involvement intensified.

A couple of years prior to Sharpeville I had tried to defend my attachment to comics. The family intellectual, my older sister, interceded on my behalf, declaring I was better read than other kids my age. Nonetheless, mom persisted. Comics were meant for little boys but I wasn’t that kind of boy. She’d never accepted my not being the second daughter she’d wanted. That biological misdemeanour continued rankling mom for years and years.

The vocational psychologist I was sent to agreed with mom. Dad cut the deal – I had to choose between university and comic books. I chose: the collection was dismantled and scattered amongst local charities – at the least I should’ve kept Captain Marvel Adventures #113. I did not. 30 years later an assiduous friend tracked it down.

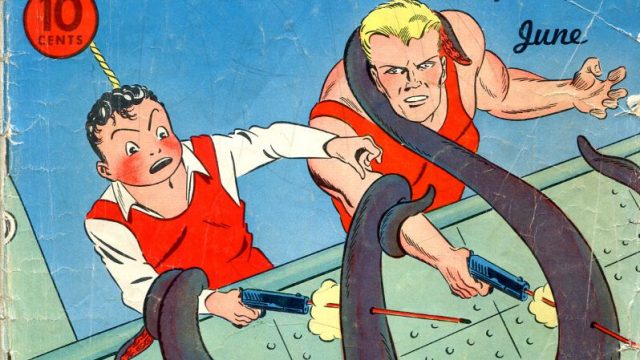

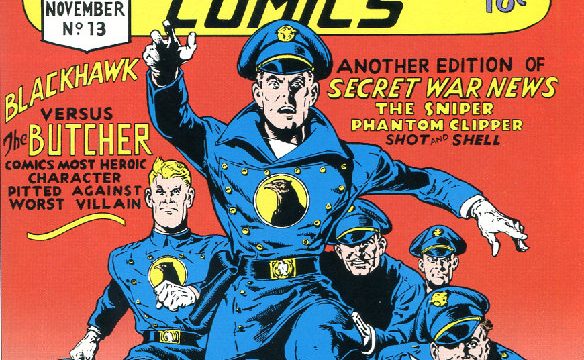

The childhood collection had a certain tenor. I disliked comics overburdened with words. This included the Lev Gleason Crime Comics and Little Orphan Annie – both of whom I now revere. Nowadays, I tend to accept some overload of words as a good thing but at its best the comic culture is dependent on the visual sequential, incorporating a balance between word and image. In childhood when I wanted a preponderance of words I turned to literature with hard covers.

I wince at publications described as comics when actually they are illustrated stories parading as graphic novels – the contemporary label for comics. It’s the literati’s attempt to shed the traditional opprobrium attached to comics.

That early collection included a complete run of Joe Palooka heavyweight boxing champion of the world. In the 40s and 50s Harvey Comics reissued (or reprinted) the 1930’s newspaper strips of Palooka slotted in alongside or in between Palooka’s patriotic wartime exploits. In apartheid SA boxing was the sport of freedom, on a par with the attitude to jazz. Boxing was to some degree, colour blind.

What stayed strongest in my memory were the comics that appealed to the neighbourhood kids of all colours. The most widely popular comic was probably Donald Duck which I have to admit I never took seriously until adulthood.

The art of Jesse Marsh transcended the conceit of white supremacy in black Africa. His rendering of Tarzan – again – was enjoyed by all the neighbourhood kids. Those childhood favourites all reappear in The Rakoff Collection.

I collected westerns oblivious to the all pervasive lie about the cowboys; black people had been completely whitewashed out of American history. Cowboys were ‘whites only.’ In the 1970s I learnt that a quarter of all the cowboy population was black. This included veterans and survivors of the Civil War searching for a fresh start in the frontier territories. This all came to my attention in the comics through the historically informative Golden Legacy series.

As for the superheroes in my childhood, I was inclined to swapping them at the ‘bioscope’ on Saturday mornings. The only superhero I collected was Captain Marvel Adventures. Even in childhood it registered that the clear line artwork and wit of the artist CC Beck were beyond the ordinary. It’s not surprising that Captain Marvel outsold Superman and got destroyed in 1954 for that – incriminated for plagiarism.

The dispersal of the comics cut me loose. I went from an unfulfilled subversive to street hooliganism vaguely protected by the superhero lifesaver – the secrecy of dual identity. Without the comics what was repressed became expressed. I was spiralling out of control. My parents had no idea how the comics had kept me sedated.

After a couple of years of wildness, a return to university – social anthropology and psychology – connected me with a small group of subversives. They and my involvement with the theatre saved me from what I was heading towards and curtailed my adolescent extremes.

In the end the group leader told me that I had to get out of South Africa quickly. One of us, it was discovered, was a paid police informer. At the same time (on the same day it so happened) a detective – an Afrikaner pal from schooldays – gave me a warning, ‘weren’t you thinking of leaving SA? Could you be out of the country before ten days?’

Another Afrikaner working as the theatre critic on Die Burgher used his well-connected influence to sort out my passport. Within the ten days I was on my way overseas. Soon after my departure the handsome, urbane Xhosa leader of our group was arrested.

In England in 1961, living in Chelsea – sans comic books – after a year of menial jobs (Harrods Xmas toy department and Cooks Travel Agents doing itineraries) I got underway in the film industry, and I fell in love with a bubbly, curly haired, dimpled English girl, Erica. Ignoring her upper crust background we got engaged. We planned to have a family. I met the parents. She met my father when he came over from Cape Town. It was the happiest period of my life. But class pressures and disapproval of me came into play. To get away from me my fiancée was shipped off to Switzerland. She promised to come back and marry me. She never did. Her brother was an influence. He cited cultural differences. He was only trying to protect his younger sister. Her privileged background got the better of both of us. It was 1963. The swinging sixties had just got started. I could see no way forward.

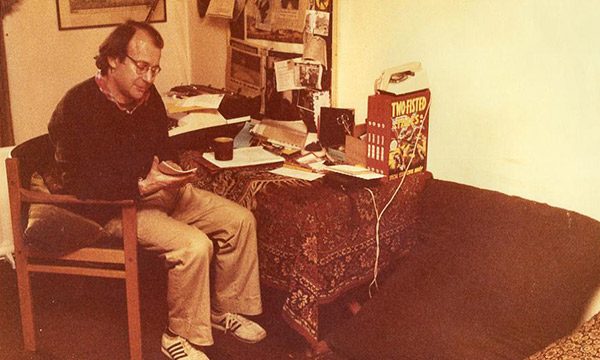

The comics issue had never featured throughout our relationship. Unbeknownst to me my five year stint in the comic book wilderness was almost over. With the ending of my relationship there was a huge void yearning for something. I moped in semi-isolation in my Edith Grove flat just off the Kings Road from where I haunted the National Film Theatre and searched for a way into films. I’d got into a processing laboratory to acquire the necessary union ticket. I’d then got a trainee job in the cutting rooms of a documentary company.

My favourite hangout place became the Victoria and Albert museum. It had a vast, seedy café. Formica table tops were cracked with curling edges. Rusted metal legs supported green plastic seats with tears everywhere. But it was spacious enough for me to happily lose myself, scribbling, reading and scrutinizing the museum programme.

One of the highlights of an Eisenstein exhibition was a talk by the corpulent, ebullient left-winger, Ivor Montagu who had worked with Sergei Eisentein. With the exhibition there was a screening of the material from which came Que Viva Mexico! The production had been abruptly suspended by the Hollywood moguls as soon as they saw the material. I too was taken aback as the exquisite but explicit black and white images filled the screen.

This lascivious orientation fitted with a large black and white drawing of Christ nailed up performing an irreverent act with a man crucified alongside of him. It was a murky portrayal and consequently my memory is hazy. But the facts all seemed to suggest that Eisenstein had a somewhat strange sexual mentality; certainly for the 1960s reflecting on the 1920s.

The long and short of it was I considered the museum to be the finest emporium I had seen. I liked the British Museum and the Tate and the Wallace Collection but they were not remotely like the V&A.

However, before I could fall unreservedly in love with the museum I had to check out something. Many, many years later I used this awful tale in my keynote address to a comic’s symposium at the V&A. It went something like this…

I and my siblings were taken by L Mabusela to visit the Natural History Museum in the botanical gardens in the middle of Cape Town. I got lost and found myself surrounded by gargantuan cabinets containing tableaux of the hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari. I was six years old and the same size as some of the fully grown bush people. They were so lifelike and their eyes so penetrative that I was frightened out of my wits.

L Mabusela was too far away to possibly hear my anguished cries. Nevertheless, she ignored the apartheid laws. There was only one day allowed for non–Europeans. It was not that day. I was in tears by the time she swept me into her arms. The figures that so frightened me, the eyes that terrified, were people killed on commission and preserved for display.

Before I could freely commit myself to falling in love with the V&A I had to verify that nothing as vile as those hunted down Bushmen, or San people, were anywhere in the museum. They weren’t. Consequently, my affection for the museum was established freely and unopposed.