I have no inclination to justify my interest in comics. It’s enough to read them. In childhood the American comics were unique. It was similar to Hollywood. Though conceived in other countries, America was where the culture developed and flourished. The size, the shape and the substance of the American comic book opened a world of retreat, ownership and collectability.

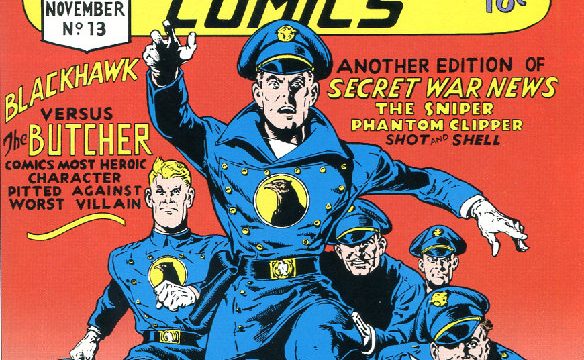

I relished smelling a page and guessing which decade it reeked of. Checking out the cover I’d guess the year of publication. Eventually I’d recognize most cover artists – at a glance.

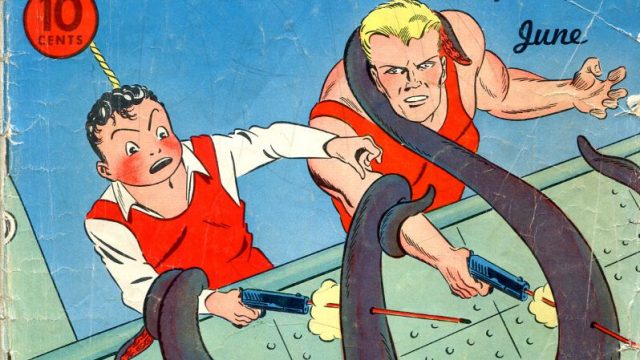

My favoured period was the 1930s, a high point in the annals of the syndicated newspaper strips and also a great decade for Hollywood. From 1933 the foremost newspaper strips were reissued in comic book format. As for nostalgia, forget it. My passion was for the retro aspect – perhaps. I hope I’ve articulated if not the credo, then the essence of my personal addiction.

Sometime in the early to mid 1970s:

At the end of a cul-de-sac in Camden Town, kids and adults clamoured at the doors to get inside the church hall taken over for the day by a comic book mart. I was with Mark – another freelancer from the cutting rooms. I spotted a dealer I knew heading for a side door. Mark and I nipped in after him. I usually managed to get in before the doors opened. Most of the dealers knew me.

Inside I flitted past a few tables – too contemporary. I didn’t need to buy that at a mart. Those imports were available at Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed in Berwick Street amidst the fruit and vegetable market, conveniently near to the Soho cutting rooms. A descendent of the author of Dracula, Bram, owned and ran the shop. From way behind, his vociferous blond partner ranted about the cult band Chili Willi and the Red Hot Peppers. Bram wore his long hair down to his bum. Eventually he threw in the comic book towel, and became a wrestler.

It was a pain to shop at Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed. It was pleasanter when the shop had started in Covent Garden. This was the first pukka West End comic shop. It’s where I bought the epic tome the 1967 Saga de Xam, a masterly work reflective of the interplay between cinema and comics paramount in French culture.

The other comic book shop I frequented was Forbidden Planet in Denmark Street owned by Nick L – the straight guy that never changed. At least his shop didn’t have the barracking blond lurking in the shadows boasting about being a fan of the up and coming cult band.

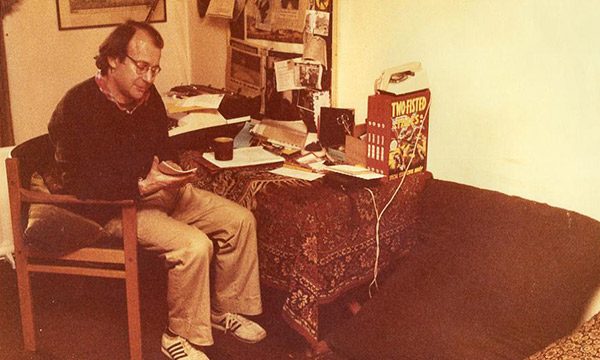

Back at the Camden mart I found a dealer’s table which looked interesting. I flipped through a pile, pulled some items, and hurried off to the adjacent dealer’s table. A box of about a hundred old comics was plonked onto the table. The dealer knew what I was after. I picked out nearly half the box and rushed on. I wanted first dibs on what I wanted.

Mark followed close, ready for anything. The banging on the doors got more impatient. I moved faster. I’d just skimmed through the last dealer I’d aimed for when the doors swept open. The horde charged in and spread out. I held back for the tumult to subside. It didn’t, it wouldn’t. I plunged in. Mark followed as I back trailed from dealer to dealer selecting from the stashes I’d amassed. I rejected between a quarter and a third of the initial selection. I wrote out Wells Fargo cheques, and hurried onto the next table. A dealer admiring my cheque said he’d like to frame it. Someone always remarked on the picturesque tilting stagecoach on my cheques – probably a painting by F Remington.

I’d met an American at a party. We talked comics. He worked for Wells Fargo. He offered to get me an account. They were big on the west coast. In London it was a service for travelling Americans, a sort of clearing house. I got an account and a colourful cheque book.

I was with Wells Fargo for years until the bank stipulated that one had to have a hundred grand in each account. I wasn’t in that league but I got terrific treatment in grand surroundings. It was mistakenly thought I was a pal of the owner.

With an armload of comics, Mark traipsed behind me. We passed Dez who was buying, not dealing. He gave me a rundown on the dealers I might have missed, likely to have what I was looking for. In that way Dez was generous and astute.

My favourite dealer, the zany BJ, was cackling surrounded by his brood. He said something to a punter which was untrue and winked at me – of course he was willing to do a deal! Wasn’t he the most reasonable shark in the business? One of the BJ kids helped us ferry my booty out to Mark’s car, a dark grey state manufactured Russian Lada Riva.

As we drove away Mark said he was staggered by the amount I’d spent. I hardly heard him. I was too intoxicated by what the hunter-gatherer had come away with. I’d made a terrific score.

I was impatient to get the comics home and read. I was especially pleased because I’d found some Joe Palookas. Joe Palooka was an anomaly. Though, arguably, the most successful syndicated strip, I never met another Palooka collector. One thing was for sure – creator Ham Fisher was no great artist. Anyway, I’d bought the oldest Palooka I’d seen. On the cover Joe is behind a machine gun and Adolf is dancing and sweating: ‘Haf a heart, Joe – mine goose step ain’t vot it used to be!’ Joe Palooka, number 2, 1943, condition fair.

Mark had noticed collectors with checklists. I didn’t have any lists. Occasionally I doubled up, but not often. Mark asked what I intended doing with the collection. I told him I was not going to keep them forever but also I was not going to become a dealer as many collectors needed to, to feed the habit. I could always get a film job.

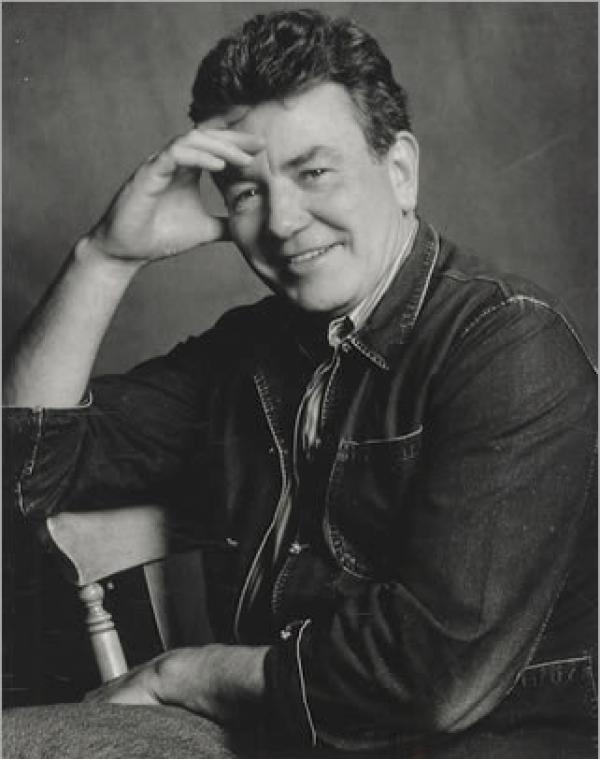

Albert Finney, the star of Tom Jones, deferred his salary for a percentage when the film got into trouble. Consequently he made a fortune and set up Memorial Enterprises Ltd. I worked for Memorial on four films. Albert launched a string of first time directors including Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Tony Scott.

Finney had turned down the lead in This Sporting Life. Lindsay never forgave him. When Lindsay heard I’d got friendly with Albert he was outraged. When he learnt it was connected to comics he said we were a couple of idiots who deserved each other.

Albert had been round to my flat in the World’s End in Chelsea for comic book sessions. His chauffer waited outside with the silver Rolls Royce parked illegally in Edith Grove as the traffic thundered by. At the end of a couple of hours Albert said he didn’t know why but he’d like to come back. The next day he arrived ready for more.

I had a subscription to Russ Manning’s Tarzan published by Gold Key, previously Dell Comics. Number 168 from 1967 caught Albert’s attention. Drawn by Manning it followed the ape man slipping into the ruins of Opar. There were gold bars in the vaults.

Repeatedly the ape man fought the white hirsute dwarves ruled by the beautiful La, Queen of ruins. She loved the lithe, sleek limbed Tarzan. She either tried to seduce him or kill him. He resisted both her approaches – time and again.

Albert was impressed with the artwork and the sense of cinema inherent in the placement of frames. The sequential drama races from frame to frame and page to page. The lighting and the angles are flawless, and the flow fluent yet the borders are wild and higgledy-piggledy. Triangular and oblong shapes encase the image and are as diverse as the dramatically contrasting points of view. The shadows and the perspective are exquisite.

The Tarzan artwork placed Russ Manning in the forefront of the interchangeable grammar of comics and cinema, almost as substantially as the Milton Caniff Terry & the Pirates in the 1930s. Caniff was admired as the Rembrandt of comics. The earlier Tarzan also much admired was by Burne Hogarth who was termed the Michelangelo of comics.

I had an idea for a sci-fi comic book, wrote something and engaged a sequential artist to do some colour pages. I kept on popping in to Memorial to show Albert The Saga of Greg Portina. Albert offered to finance the project. I never took him up on it. That was then – now I cannot say I would have turned down the comics for a career in film, unlike Nick L of Forbidden Planet and Titan Publishing, who chose comics after studying film.

Albert played daddy Warbucks in Little Orphan Annie. He was questioned about his interest in comics. Doing the interview was my publicist friend Barbara at Columbia-Warner. She recalled Albert visiting me in Edith grove. He answered that he was never interested in comics. He was interested in my interest in comics.

While working on Deliverance, the director John Boorman introduced me to a friend who’d published what John described as a comic book. I read it. There was no awareness of any comic book grammar. There was nothing sequential and no sense of frame. It was an illustrated picture book. The author was a gangly schoolteacher. Boorman was a nice guy. I didn’t want to be picky. I said as little as possible. I’d been offered a generous credit on Deliverance.

The author of Deliverance – the poet James Dickey – had it in for comic books. On the academic circuit Al Capp of L’l Abner commanded more per lecture than James Dickey. Call it a culture clash.

Deliverance was shot in the Appalachians and edited at Ardmore Studios in Ireland. Sue M and I shared a house on the coast in County Wicklow along with Tom P the editor. I was buying comics from America, and from BJ in Wandsworth. I had them shipped to Ardmore. When it came to leaving Ardmore I had the comics shipped to London with the film cans.

Towards the end of our stint at Ardmore Sue and I went to a woollens shop in a County Wicklow backwater. Mounds of pullovers, scarves and cloaks were spilling off the one table and onto the floor. There was hardly room for customers. I heard a booming American voice. I peered around a pile of blankets and saw this big fellow.

I know you! I blurted. With good natured aplomb the big man flung his arms up and wearily said – I am not Burl Ives. But then who are you – I went on. He was Robert Altman, the American director working at nearby Ardmore. He asked who I was. I said he wouldn’t know me. I told him my name. He’d heard about me. He wanted me on his film Images.

I met Altman’s editor, a long haired Aussie, with a nervy disposition and a stammer when he got agitated. He spotted the comic in my pocket. It was an early 1950s piracy comic published by one of those small companies such as Ace or Toby Press. I showed him the comic and said he could borrow it. By the time I exposed him to the Furry Freak Brothers by Gilbert Shelton we were friends for life – or so it seemed.

I had a slew of comic book conversations with the American lawyers of Deliverence. Later I heard one of the lawyers bought the rights to X-men – ages before Superman reached the screen. The marriage between comics and film was drawing closer in Hollywood.

In between leaving Deliverance and starting on Altman’s Images I was mooching about the NFT having just seen the Monty Hellman film Two Lane Blacktop. I thought I saw Clint Eastwood coming towards me. It wasn’t Clint Eastwood, but he was making for me with a girl next to him looking like she had flowed in from Haight-Ashbury. The chap wore a long brown coat, was tall and wore a hat right out of a Spaghetti Western. He may not have been Clint but he sure looked the part. I wondered if he’d been drawn to me by the comic in my pocket.

He sidled up to me and without looking at me asked where Monty was. I asked why he was asking me. He said I looked like I’d know. I told him he looked like Clint Eastwood and I knew nothing about the director Monty Hellman. The Clint lookalike (Al Logatelli) told me he worked in the art department for Bob Altman. I said some coincidence, and told him I was signed up for postproduction on Images.

Logatelli was the art assistant on Images. He wasn’t supposed to be in London. I was asked not to tell anyone that we’d met – in London. Over the next week we saw a fair bit of each other. Logatelli was interested in comics, especially the undergrounds. He had them all at his fingertips. He asked for Robert Crumb. I gave him a Crumb. I reckoned that the crew of offbeat young Americans I was going to work with would all be interested in comics. The writing was on the wall.

Lindsay had a film – O Lucky Man! The production supervisor contacted me. He’d heard I wasn’t happy on Images. Though the shooting schedule was two months away Lindsay wanted me to start immediately. He wanted me to prepare a film on a mythical African State for back projection. I’d read the screenplay and I was not enamoured. Whether I was willing to forego a year’s reading of comic books in order to serve Lindsay was a moot point.

The production supervisor was abrupt and a bit of a Colonel type – puffed up. I told him what money I wanted. He snapped that was a preposterous figure and handed me a piece of paper saying that was what I’d be getting. His manner was unpleasantly rude – not at all what I’d anticipated or been used to.

I unfolded the piece of paper. I saw the amount and asked what was going on. He tugged at his moustache and smiled. It was conspiratorial. He spoke softly – I know all about you and Lindsay Anderson. I don’t want you as an enemy.

What he’d proposed was a lot more than I’d asked for. That settled I got a clause about comic books inserted into my contract with Warner Brothers. I did not tell ‘Colonel’ about my history over comics with Lindsay. There it was, I was back with the nearest thing to a superhero I had known. I was on board for Lindsay’s O Lucky Man! It would be one of the toughest years of my career but with an income to buy more comics than I could dream of.

If only I liked the screenplay as much as I’d liked the script of If….

I came home from the cutting rooms. My louche flatmate was serving tea to a big girl sounding off. She flapped about on a floor cushion just missing hitting her smaller, shapely sister alongside, engrossed in a comic book. The big sister yapped that her exuberance was because she was an American from Oregon, and she could not be blamed for that. Plus it was the sister’s first visit to Europe. I thought she was a caricature of a Robert Crumb piece of beef but louder and more out of control. A sense of a future of unhappiness rolled off her overgrown frame.

The girl curled up on the other half of the same cushion was in a faraway place devouring a Furry Freak Brothers. I went over, took her hand and led her out into the hallway. We stopped. We kissed for the first time. I asked her name. She told me. I latched onto her initials – KK.

Yap-yapping, the sister came out into the hallway. They had to leave. I gave KK my phone number. The next day KK telephoned and said she loved me. She had a soft beguiling American west coast accent.

KK came round wearing a hippie styled multicoloured sequinned dress and baked a carrot cake. It was a wonderful heady moment. But she had to rush off to collect her two year old, Arrow.

Within a couple of days the two sisters were back. I came home from the cutting room to meet the little tyke – Arrow. He was at my desk, kneeling on a chair defacing a pre-code ACG western. KK was horrified. I picked Arrow up and carried him away from the comic. He tried to hit me.

A few days later my louche flatmate flew off to work in Athens. KK and Arrow moved in. Arrow was wild. KK had a smile warm enough to melt a room.

Unfortunately things got shaky with the newly acquired readymade family unit. It seemed impossible. I couldn’t take any more. KK and Arrow flew back to the States. She didn’t know why they were leaving, and neither did I.

I missed KK and Arrow. KK was the only female I’d been involved with who was seriously receptive to comics. Since that first incident defacing a comic, Arrow had kept away from the comics he was not supposed to touch. He had a lot going for him. He was irresistible – like his mom. Given my addiction to American comics I suppose it was inevitable that I’d fall for an American.

My old flatmate came back from Athens. Lindsay, after meeting the louche Levantine, decided that I needed protection from my friends. I had talked about KK and Arrow. Lindsay thought a readymade family was what I needed. Lindsay and his intuition; often it was brilliant but not always.

I didn’t hear from KK for ages. Ever prescient Lindsay had anticipated I’d be hearing from mother and son. As he predicted I got a letter from KK – lovely handwriting, terrible spelling. How was it Lindsay had known so much about things he knew nothing about? What could I have said to Lindsay that I hadn’t told myself?

After nearly a year KK wrote that Arrow hadn’t forgotten me or the comic books. She asked me to visit them. Something was amiss, something was off-kilter about the invite to Oregon. I couldn’t put my finger on it.