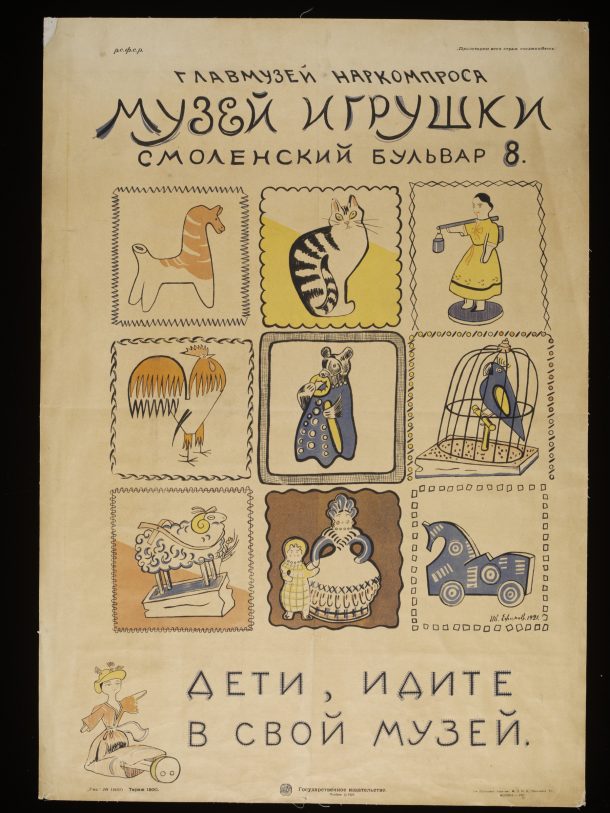

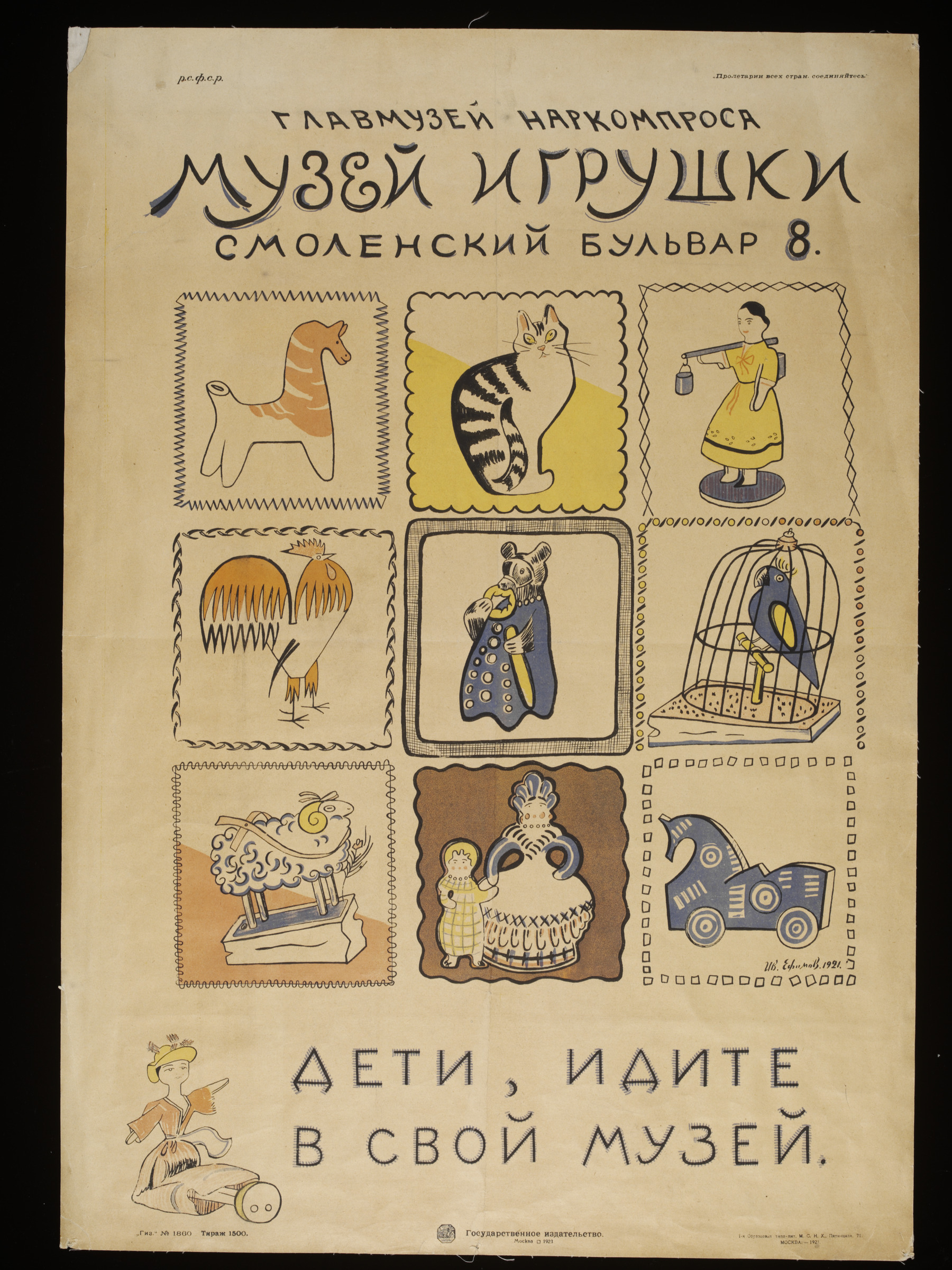

I’ve been learning Russian for a few years and each term in class we look at a different theme, most recently childhood, toys and games. I’ve been looking for objects in the V&A’s collection that will help me with this topic. As our own Museum of Childhood is about to undergo an exciting redevelopment, I was delighted to find a poster at the V&A for a Russian toy museum [музей игрушки – musey igrushki].

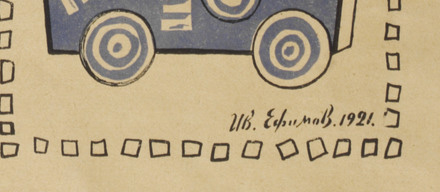

The poster was made in 1921 and has the signature of the artist – Efimov.

When the poster was acquired by the museum, this was identified as the Boris Efimov who was famous for designing political posters, particularly during World War II and the Russian civil wars of the early 20th century. He worked as an artist and teacher of art until his death in 2008. However, with many thanks to blog reader Irina Zhigmund who left me a comment below, this is now identified as Ivan Efimov, a sculptor and artist, whose interest in folk art, puppets and animals would make him a perfect choice for a poster for a toy museum.

Toy-making is an important folk craft in Russia, with a long history and strong traditions. Its origins are in artifacts made for ancient rituals such as celebrations of nature or community. Toys were often made of wood or clay, but sometimes of other more unusual materials such as moss or straw. Cottage and village industries making toys grew up around villages such as Dymkovo. By the 19th century, toys were not only ritual folk art and playthings, but also collectables.

The Toy Museum was founded in 1918 by Russian artist, critic and collector Nikolay Dmitrievich Bartram, using objects from his own collection of toys from the 18th and 19th centuries. Other collectors donated objects, but a more dramatic acquisition by the museum were the toys that belonged to the Russian Tsars. After the Royal family were killed in 1919 their belongings were passed to the state, and their exquisite playthings to the Toy Museum. Although the museum featured such exclusive objects, our poster celebrates the folk toys more familiar to, and characteristic of, Russian everyday society.

A whistle in the shape of a horse is the first image at the top of the poster. Whistles are an important toy in Russia, often made of clay and shaped into animal shapes, usually horses or roosters. They were used in a spring whistle festival in the district of Kirov (which includes the toy making village of Dymkovo) until the 1920s.

The clay shapes were painted white, then decorated with patterns in characteristically bright colours. The colours have meanings attached to them: green for nature, red for strength and health and blue for the sky.

Human figures made of clay are also part of Russian folk craft and toy traditions. They too would feature bright colours and patterns on their clothes. Often a number of figures would feature together in a set portraying a village feast, or a family gathering.

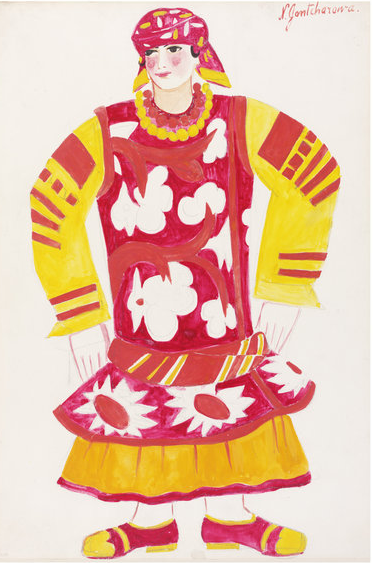

The Russian word for a potter is гончар ‘gonchar’, which must be the route of artist Natalia Goncharova’s surname. Her designs for ballet costumes were inspired by the bright colours of Russian folk arts.

The poster does not include an image of what we now think of the most Russian of toys: the matryoshka nesting dolls. Designed by Sergey Malyutin and Vasily Zvyozdochkin in 1890, and influenced by similar figures from Japan, perhaps these were not Russian or traditional enough in 1921 to earn a place on our poster.

The museum was initially located at 8 Smolensky Boulevard, in Moscow, which is the address on this poster.

In 1931 it moved to the town of Zagorsk (previously called Sergiev Posad before the communist government renamed it to remove the name of St Sergei). Sergiev Posad is one of the areas of Russia famous for toy making, particularly dolls. There is a nice example of a wooden doll with fabric clothes sitting at the bottom of the poster.

A research institute for toys was opened in Zagorsk in 1932. Here, toy makers were trained, and new technologies for toys developed. Traditionally, Russian toys with moving parts were very popular. Made of wood, they would use levers to make them move, or strings attached to a wooden weight underneath the toy that when swung around would make the figures move in sequence. Some of the toys on the poster have a base which makes me think they would have moving elements, such as the parrot – perhaps he would flap his wings and move his beak.

The text at the bottom of the poster states: ‘Children, go to your own museum’.

The inclusion of ‘свой’ – your own – is a nice touch to make children feel welcome and at home at the museum. The museum is still open in Sergiev Posad (it returned to its previous name in 1991 after the fall of Communism), and welcomes children and adults alike to celebrate toys, playing and childhood, as I am sure our own Museum of Childhood will do when it reopens.

Thanks Ruth. I found your blog very interesting and informative. ( more please)

Спасибо! it’s not Boris Efimov, it’s Ivan Efimov https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Efimov

Irina, большое спасибо. I have edited the blog to credit Ivan, and updated the object information on our catalogue.