Japanese woodblock prints produced during the Edo period (1615-1868) are famously known as ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’). Distributed in their many thousands, these affordable pictures played a significant role in information-sharing in bustling cities, from the latest fashion trends to new forms of entertainment.

A lesser-known genre has recently gained topical relevance. Hashika-e, or ‘measles prints’, were mass-produced at the height of Japan’s worst outbreak of measles in 1862. Measles was a common infectious disease in Japan, and an epidemic struck every 20 to 30 years during the Edo period. The devastating crisis of 1862 is thought to have claimed thousands of lives in the city of Edo (present-day Tokyo) alone. Outside of the field of medical history, these relatively rare prints had received little attention until last year.

Utagawa Yoshifuji (1828–87), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.13574-1886

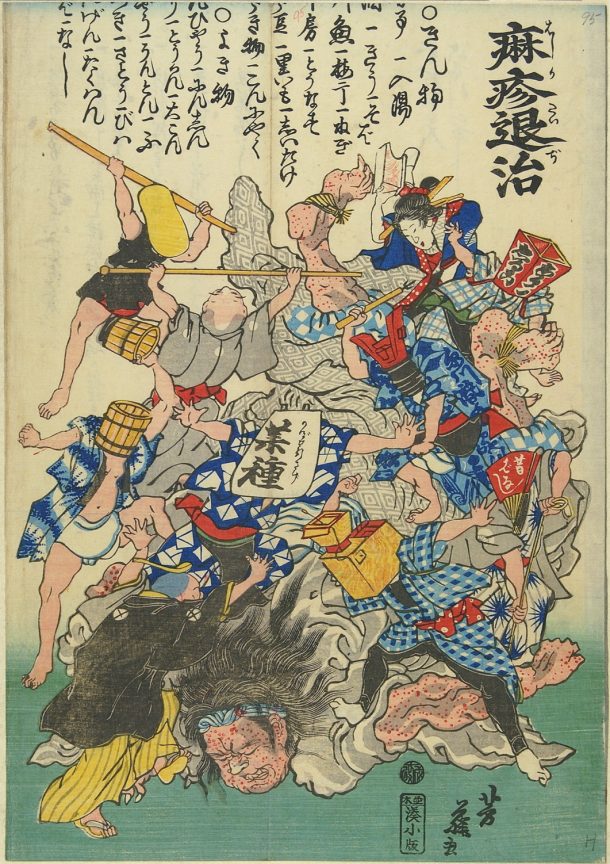

Measles prints reached Europe during the age of Japonisme – a period in the 19th century when many artists and connoisseurs in the West took great interest in art and design from Japan –, but no study had focused on their existence in European collections. The most curious examples found in the V&A collection are the social satire of the epidemic which portrays winners and losers of the crisis. In the example above, by Utagawa Yoshifuji, four figures representing the businesses severely affected by the disease are tying up a sleeping measles demon child, covered in reddish rash, in an attempt to bring the outbreak to an end. The virus was often depicted in a humanlike form. The losers here include a sake seller with a two-handled sake-bucket head, and a party boat owner with a boat-shaped head. They were both victims of a warning against drinking during the epidemic. In contrast, the pharmacist, who has notoriously prospered from the epidemic, is shown in the lower left corner on his knees, imploring the others to spare the demon child.

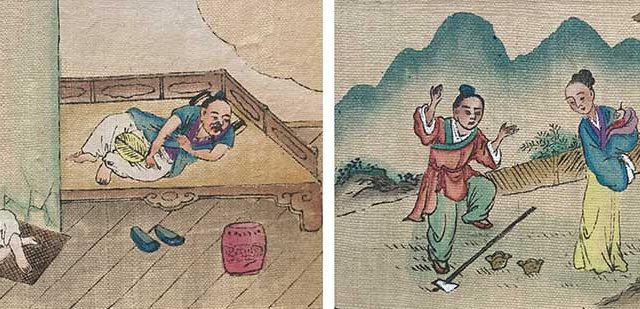

Regardless of design differences, almost every measles print included textual information on dietary advice and what not to do while recovering from the disease, sometimes of a dubious nature. Here, sexual intercourse and eating greasy food are advised as things to avoid.

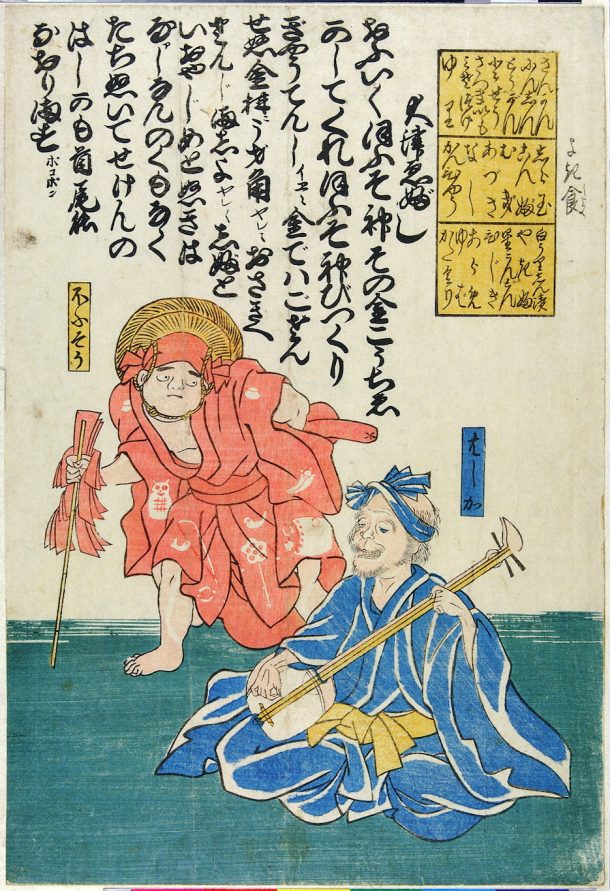

Utagawa Yoshimori (1830-84), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.13843-1886

The print by Utagawa Yoshimori similarly criticises greedy winners of the epidemic economy by depicting the virus, this time as the measles deity dressed in a plain, yellow, kimono, protected by the medical doctor in black jacket and the pharmacist in blue stripy kimono. Courageous men of Edo are kicking the deity out of the city.

The picture implies people’s dissatisfaction with medical doctors and the inaccessibility of overpriced remedies. Due to the long intervals between measles epidemics, most doctors were inexperienced in treatments for the disease.

Utagawa Yoshimori (1830-84), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.13841-1886

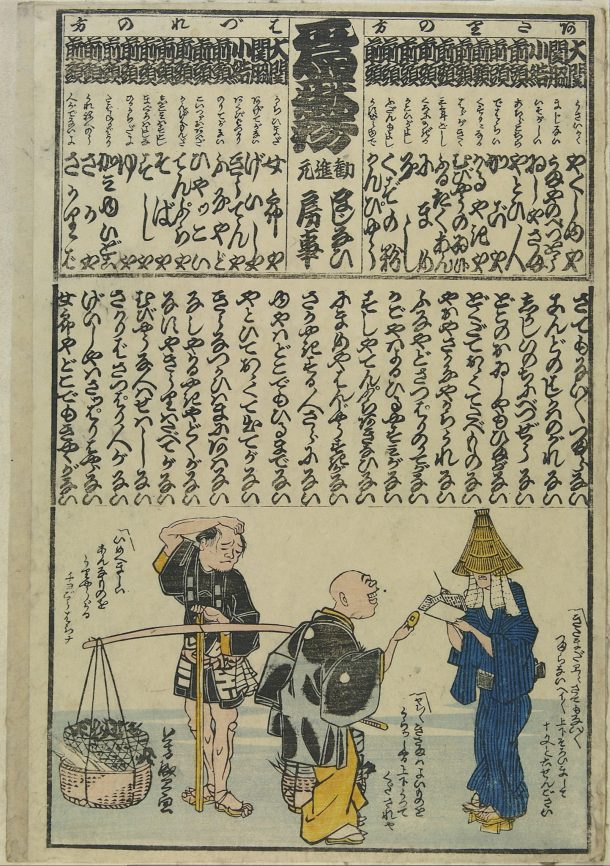

Another print by Yoshimori (above) provides further details of the epidemic economy. Modelled on the traditional presentation of graded ranking lists of sumo wrestlers, it shows a ranking of the two groups – ‘those for whom the epidemic is a blessing’ and ‘those for whom it is financial hardship’. The biggest winner is the pharmacist, followed by the stable keeper (due to the popularity of a horse-related magical rite to alleviate symptoms, such as placing an empty horse-feeding bucket over the head of a sufferer) and the medical doctor. The top three losers are the brothel owner, the geisha performer and the moxibustionist (a traditional healer using incense on the patient’s body), whose work all involved close physical contact. The illustration shows a news-sheet seller, known for often reporting dubious information on the disease, offering overpriced latest news sheets. A street seller of vegetables makes a painful expression facing the rise of an untrustworthy business.

Utagawa Yoshimune (1817-80), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.13861-1886

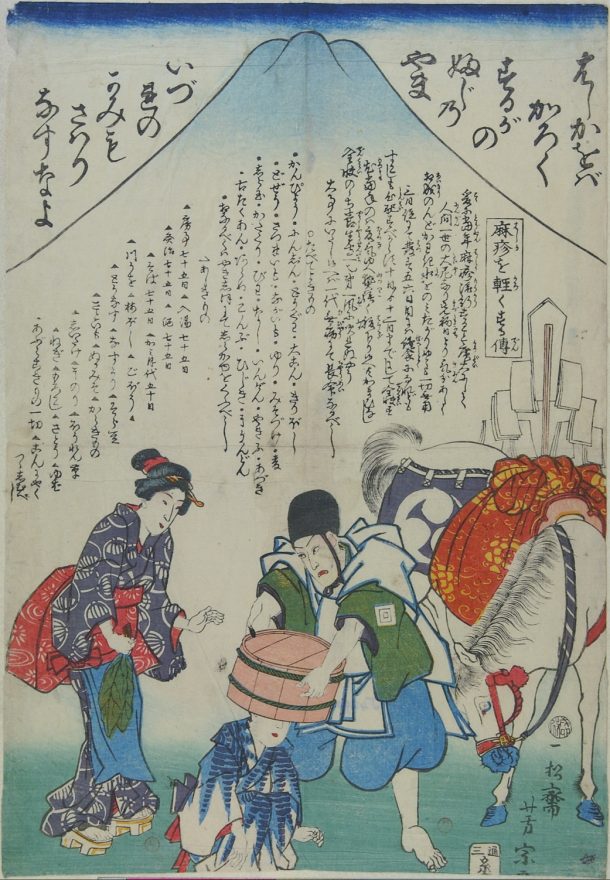

Having limited access to effective medical treatments, magical rites often remained as people’s last resort, particularly at the beginning of the epidemic. Some measles prints were designed as talismans against the disease and were placed on a paper screen or wooden door to ward off the virus from households. In this print above, a man places a sacred white horse’s empty feeding bucket over a woman’s head. The woman to the left holds holly leaves, which were also thought to have protective powers. Mount Fuji towers in the background as a symbol of immortality.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-92), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.14231-1886

Pictures of celebrities of the day who recovered from the virus were also popular. Like every infectious disease, measles affected people of all social classes. The announcement of the recovery of famous kabuki actors gave people hope and created a sense of social solidarity in the fight against the virus. Two such examples were Ichimura Uzaemon XIII and Kawarazaki Gonjūrō I, young actors who went on to become stars of the Kabuki theatre in the Meiji period (1868–1912).

Measles prints published 159 years ago reveal surprisingly similar social changes to those we have seen in the past 18 months of COVID-19. The epidemic drastically transformed the economy, creating clear winners and losers. People’s home confinement left restaurants, public bath houses and brothels in the city of Edo empty. The virus did not discriminate and could infect all people, which brought a strong sense of social solidarity – a feeling we see shared globally today.

The publishing industry was a remarkable winner in the crisis. It was prepared to keep producing a variety of full-colour woodblock prints throughout the epidemic. Today, as we continue experiencing a relentless overload of daily updates on COVID-19, it is not hard to imagine the people’s thirst for information at a time of health crisis.

Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.5391-1886

Utagawa Yoshifuji (1828–87), 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.13607-1886

Artist Unknown, 1862, Edo (Tokyo)

E.14425-1886

Further Reading:

‘Transcribing History’, Cambridge University Alumni Magazine, Issue 92, 8 April 2021.

Hartmut O. Rotermund, ‘Illness Illustrated. Socio-historical Dimensions of Late Edo Measles Pictures (Hashika-e)’, in Written Texts – Visual Texts: Woodblock-printed Media in Early Modern Japan, ed. Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart, 2005, pp.251-282.