May 2021 saw some of the most intense violence in Israel and Palestine for years. Unrest was sparked by the forced evictions of Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood of East Jerusalem, and the storming of Al-Aqsa Mosque by Israeli forces while Muslims were gathered to pray on the last Friday of Ramadan. Israel launched airstrikes on the Gaza Strip for eleven days, killing 230 Palestinians, including 65 children, injuring 1900, and displacing 70,000 Gazans from their homes. Hamas’s retaliatory rocket strikes killed 12 Israelis. By the time the ceasefire was negotiated on May 21st, there had been widespread destruction of infrastructure in the Gaza Strip, including damage to the already fragile healthcare system.

When demonstrations took place around the globe, expressing solidarity with this latest assault on Palestinian lives, ubiquitous at these protests was the keffiyeh, the iconic symbol of support for Palestine. However, in the era of Covid-19, a new twist on this icon could also be seen – the keffiyeh facemask, an example of how long-established symbolic objects are finding new forms of expression, to meet the demands of a pandemic compounded by a wider political and humanitarian crisis.

The keffiyeh (or kufiya, as it is properly transcribed from classical Arabic) is a metre-square piece of cloth, usually woven from cotton, with a distinctive black-and-white checked or houndstooth pattern. It would typically be worn on the head, folded in half diagonally and held in place by a head-rope (‘agal), originally made from goat or camel hair or wool. The keffiyeh could also be wrapped around the eyes and nose to keep dust out of the face. Until the 1930s, this cloth was the characteristic head-covering of the Bedouin, or Arab nomads. Worn by men, it protected them from the elements, and visually distinguished them from those who lived in more settled environments like villages or towns.

The important role of peasant farmers (the fellahin) in the Great Arab Revolt of 1936 – 39 – the uprising against the British Mandate government of Palestine, demanding Arab independence – politicised the keffiyeh. It came to be widely adopted by urban dwellers as a symbol of Arab/Palestinian identity and an expression of nationalism.

This symbolism only grew more potent as these struggles became more intense. Following the 1947 – 48 war, the state of Israel was founded and 770,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homes (known as the Nakba to Palestinians). Further dispossessions took place after the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967. This sparked the use in Palestinian nationalist poetry and rhetoric of symbols connected with a rural way of life – the peasant farmer (fellah), the keffiyeh, the olive tree, the cactus, traditional crafts such as embroidery, all became, as Ted Swedenburg has put it, “allegories for Palestine, the land, and the people’s intention of remaining permanently on the land”.

Yasser Arafat (1929 – 2004) – chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation since 1969, and first President of the Palestinian National Authority until his death – adopted the black-and-white checked keffiyeh to signify that he was a man of the people. He wore the keffiyeh in every public engagement, such as the signing ceremony of the Oslo Accords in September 1993 and the ceremony in which he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 alongside Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres (1923 – 2016) and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (1922 – 1995).

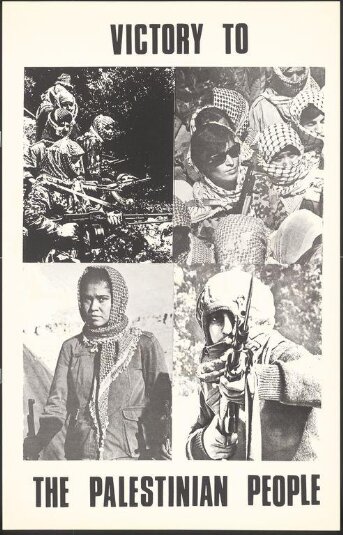

Arafat’s use of the keffiyeh as his permanent head-covering cemented its status as a global icon of Palestinian nationalism and resistance. Guerilla fighters could conceal their identity by wrapping the cloth completely around their face. Having been an exclusively male garment, it was adopted by women, such as the resistance fighter, Leila Khaled, who iconically wore it in headscarf fashion. During the First Intifada (1987) and Second Intifada (2000) it came to be worn worldwide as a symbol of protest and resistance, and solidarity with the Palestinian people.

In the past, more than 30 factories operated across Palestine producing keffiyehs. Today, only one of them survives – the Hirbawi Factory in Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank. Founded by Yassar Hirbawi in 1961, the factory houses 15 antique machine looms, though they only operate four of them these days, as sales have been in steady decline since the 1990s. This is a result of foreign-made imports, primarily from China, which are cheaper but also inferior in quality to the Palestinian-made originals.

Although the keffiyeh face mask has become popularly used during the Covid-19 pandemic, it was originally developed in 2015 in a workshop organised by the Belgian-based not-for-profit association, Disarming Design from Palestine (DDFP). DDFP develops contemporary designs based on existing manufacturing processes in Palestine, employing local resources and techniques. They aim to use contemporary design to connect consumers with craftspeople, and to provide work, fair pay, and to preserve the heritage of making. During August and September 2015, DDFP hosted two ‘create-shops’ in Gaza and Jerusalem, bringing together local and international artists, designers, and craftspeople. During a collaborative process, the participants were invited to work together to develop useful products that reflected Palestinian reality and could be produced in Jerusalem or Gaza.

During this workshop, Palestinian artist Mohammed Musallam collaborated with Gaza-based tailor Abu Alaa Ghaben to design and produce a surgical facemask from keffiyeh fabric. This proposed a unique Palestinian version of an object worn by medical staff to protect them from disease; it “symbolize[d] the need of Palestinian identity to be protected from the occupation”. According to the artist, the mask expresses the idea that his identity is the only defender for the Palestinian and his cause. The project appears on the artist’s website under the title ‘Our ID is our Protection’.

The keffiyeh mask was first used in Gazan hospitals under siege. Of course, the impact of Covid-19 could not have been foreseen when the project was first conceived, but this prompted Musallam to return to the concept. Now living in exile in Canada, where he received refugee status in 2018, Musallam oversaw from afar the production of hundreds of masks by Abu Alaa Ghaben in Gaza City. The facemask has become the icon of the Covid-19 pandemic, and textile artisans around the world have turned their skills to the mass-production of masks, especially when there has been a shortage of medical PPE. The keffiyeh masks are worn for safety but also as an act of solidarity – the perfect symbol for pro-Palestinian protests in the age of Covid.

The concern now is for rising Covid infection rates among those left displaced by the recent bombardment. The healthcare system in Gaza was already fragile – there were concerns in August 2020 that the Strip would not be able to cope with widespread infection, and even greater restrictions than normal were imposed on entry and exit. The fifteen-year-long blockade means that essential medications are consistently depleted, equipment is outdated, there is a critical shortage of medical professionals, and it is difficult for patients with chronic illnesses to travel to Israel for treatment. All of this contributed to rising tensions among the Palestinians before the recent outbreak of violence. The airstrikes in May damaged several healthcare centres, including al-Remal centre which houses the lab responsible for Covid testing, halting all testing and Covid services. One of the fatalities of the bombing was Dr Ayman Abu al-Auf, head of the coronavirus response at Gaza’s Shifa Hospital – he was buried in rubble from a collapsing building in Gaza City’s al-Wehda Street. As of the 21st of May, the total number of Covid cases in Gaza was 102,323 with 2,980 active cases. Humanitarian organisation MedGlobal worries that there will now be an increase in infection rates, as hundreds of Gazans seek refuge.

Musallam suggests the lockdowns imposed by the Covid-19 crisis offer an insight into the Palestinian experience. “Now we are all like Gazans,” he says, “trapped in place”.

Postscript: The V&A’s keffiyeh mask and Hirbawi keffiyeh have been acquired through a project to acquire ‘pandemic crafts’, handmade objects from across the Middle East that give a material expression to the global Covid-19 pandemic. This project is supported by Art Fund through a New Collecting Award. Keffiyeh masks are available for purchase through DDFP’s website.

Further reading

Disarming Design from Palestine

Mohamed Musallam’s website

Kawar, Widad, and Sibba Einarsdóttir. “Arab Men’s Dress in the Eastern Mediterranean.” Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Central and Southwest Asia. Ed. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. 170–172. Bloomsbury Fashion Central. Web. 24 May. 2021.

Swedenburg, Ted. “The Palestinian Peasant as National Signifier.” Anthropological Quarterly 63, no. 1 (1990): 18-30. doi:10.2307/3317957

Weir, Shelagh, Palestinian Costume (London: British Museum, 1989)

Related Objects from the Collection

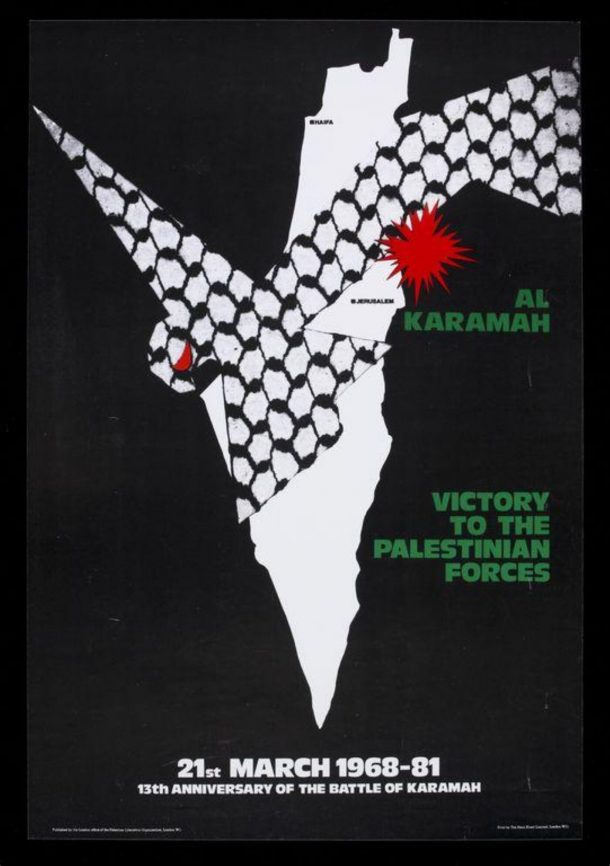

“Victory to the Palestinian Forces” issued by London office of the Palestine Liberation Organisation. ca. 1981. (V&A: E.787-2004)

Victory to the Palestinian People (Poster), The Poster Collective (V&A: E.1712-2004)